Consuming interest

Supermarket mugging

Oliver Stewart

Supermarkets smell like consumer slaughterhouses. They are crude, hideous and menacing. Compared with shops which give individual attention to customers they admittedly make quicker killings; but the means they use deserve the scrutiny of all concerned with the prevention of cruelty to consumers, notably the recently appointed defender of consumer interests, Sir Geoffrey Howe.

Their sales promotion methods rely ever less upon normal advertising and publicity and ever more upon bogus competitions, equivocal price reduction statements and the recycled selling of stamps, coupons, vouchers, token and the like.

To those who respect the meaning of words it is infuriating to be told that these tokens are ' given ' and that they entitle the holders to free gifts.' There is nothing free and there are no gifts.

Directly he passes the electronically controlled entrance and — lugging his mandatory wire basket — moves along the tinand packaged-lined avenues the supermarket customer is cornered and coerced. He is induced to buy coupons in addition to any goods he really needs. He is conned into completing idiotic, time-con suming tasks in order to recover part of the coupon charges.

Efforts are made to conceal from the public the fact that the moment they accept stamps or coupons or vouchers, in return for part of the money they pay, they surrender their freedom as buyers to the extent of the value of those tokens. They become the victims of a monetary mugging. They are, allowed to recover their money only in part, only by spending it on prescribed goods and only in specified places.

Nothing, the customer will be smoothly assured, prevents him from rejecting the stamps or coupons. But if he does that he makes a charitable contribution to the trading company which is holding him to ransom. These curious concerns obtain part of their profits from mislaid or forgotten tokens. Stamps may be lost; but stamp companies cannot lose.

This kind of coupons trading, moreover, imposes onerous and fatuous tasks upon all who try to obtain the return of their forcibly borrowed money. They must spend hours sticking miles of stamps in horrid little books; they must fill in grubby, illconstructed forms; they must engage in expensive packaging, posting and corresponding.

I have a remarkable report on a scheme in which the customers of a certain group of stores were asked, simply to collect and to send in fifteen coupons. In return they were promised other coupons "worth 75." More than 300,000 people, I am told, engaged in this ostensibly simple exercise. But they found, in the end, that the coupons they received were available only at specified stores and only in part exchange for specified goods. No mention of these restrictions had been made in the original offer.

It was as if a trader, having promised customers a hundred pounds, were then to add at a conveniently later date that they would receive the money only in the form of part payments for old boots and broken bicycles. If these schemes are designed to move rubbishy goods that cannot be moved in any other way, then the coupon buyer should be warned.

It must be supposed that, if more than 300,000 people were induced to engage in this particular exercise, in the whole country there must be many millions taking part in similar schemes.

It is a waste of energy so gigantic that it calls for attention. The public ought to be more clearly informed about what they are being induced to do. They ought to be put in a better position to protect themselves against dodginess and double-dealing.

If token trading were to cease, members of the public would be spared their ridiculous stamp-sticking chores and prices could be lowered. The trading groups would probably have to spend more on ordinary sales promotion methods, for instance on taking space in the local newspapers, on buying radio and television time, but there would still be room to reduce the total sales promotion component in the cost of goods.

Much more important, the falsification and deceit which seem to be inseparable from these forms of trading could be eliminated. Ordinary advertising may not be so compulsive as coupon advertising, but it is more open and more honest and it is more likely to help in the control of prices.

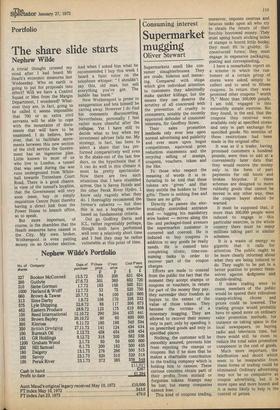

Previous page

Previous page