TURNING POINT?

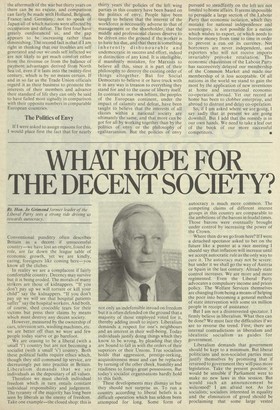

Rt. Hon. Lord Hailsham of St. Marylebone believes that we can with benefit take a leaf from the book of our more successful competitors.

Being by nature a cheerful kind of man, I do not like being a prophet of doom. But I believe that collective folly leads to disaster, and all the symptoms of our present situation seem to me to bear the Classical marks of a disintegrating society Pursuing policies of collective folly. The penalty that is always paid by such a society is always a period of chaos succeeded by a loss of freedom.

What are the marks of such a society? The first is an unwillingness to defend itself and its Allies against potential external aggression. Twice in my lifetime we have involved ourselves in disastrous and expensive wars precisely because we were unwilling to pursue policies or pay for armed forces adequate to protect either our OW n interests or the international system of values in which alone those interests could thrive. We are told that there is no danger, that there is no potential aggressor. I do not believe such talk. The whole of history proclaims that, in the presence of a Power vacuum or an imbalance of armaments possessed by independent states whose interests conflict, chaos and conflict inevitably follow. Since our own experience at Suez and since the American experience in Vietnam it seems to me that the .West has progressively shown an unwillingness to face the realities of the rapidly deteriorating situation in Africa, the permanently unstable balance in the Middle East, or the breakdown of order in Asia. So far as regards the imbalance in armaments the facts speak for themselves. The Soviets are stockpiling weapons far beyond the needs of defence and keep Permanently under arms a vast force of men quite disproportionate to any which could be mobilised against them. There is no need to attribute unworthy motives or sinister designs. The nature of communist ideology is sufficiently documented and well known to tell us exactly what they believe and the forward policy of the Soviet Union wherever there are areas of conflict is plain for all to see. A second sign of a disintegrating society is an unwillingness to accept the traditional values of a society or the authority of its established institutions, coupled with an inability to place a coherent system of values or institutions in their place. Again, the facts speak for themselves. It is a paradox of modern Britain that the more laws we pass or seek to pass the less they are respected and obeyed. Incidentally it is precisely those which are most important for the cohesion of society which seem most at risk. While motorists observe almost religiously the useless and counter productive bus lanes, and shoppers observe queues with the utmost respect, burglaries go almost undetected, crimes of violence increase in numbers, and firearms are increasingly used for criminal purposes. Mr. Hattersley can apparently get away with a law forbidding shopkeepers to offer doubtful "bargains" and placing the burden upon them to prove their innocence. But Lord Edmund-Davies and the Criminal Law Revision Committee cannot pass any sort of proposal to alter our archaic and impractical laws of evidence in cases of murder and rape.

Fly Agaric or Reason?

Disrespect for authority can sometimes take almost ludicrous forms. I speak now not simply of the authority of Ministers or Councils, but even those of scholars or experts discussing matters in their own field. I once had the ridiculous experience of seeing an Archbishop of Canterbury made to confront on equal terms an eccentric who claimed to have proved that the author of the Sermon on the Mount was in reality a mushroom, to be precise, the red mushroom known in England as fly agaric. But, of course, this open derision of things established moves well out of the field of eccentric scholarship or petty crime. A political demonstration is permitted to cover a multitude of ridiculous sins, as for instance when some extreme members of the animal lobby daubed the venerable pillars of Stonehenge in protest against the export of ponies of the New Forest, or the Headingley cricket pitch was dug up in an endeavour to provide the inhabitant of a prison with an interval of freedom, which he subsequently enjoyed for a slightly restricted period of time. The end may have been justified, since the campaign succeeded. The means adopted certainly were not.

I have so far studiously avoided talking about our economic problems, or criticising those sacred cows the Trade Unions. But those who maintain that my prophecies of doom are extravagant or hysterical should be asked to bear two things at least in mind. The first is the extraordinarily poor performance of the British nation as a whole in the last thirty years in the economic field. At first there was excuse enough to be found for this in the aftermath of the war but thirty years on there can be no excuse, and comparison can fairly be made with Holland, Belgium, France and Germany, not to speak of Japan all of which nations were affected by occupation and defeat. The first four have greatly outdistanced us, and the gap appears to be increasing rather than diminishing. The second fact is that if I am right in thinking that our troubles are self generated and our wounds self inflicted we are not likely to get much comfort either from the revenue or from the balance of payment advantages derived from North Sea oil, even if it lasts into the twenty-first century, which is by no means certain. If and in so far as the Trade Union officials regard it as their business to promote the interests of their members and advance their standard of life they can only be said to have failed most signally in comparison with their opposite numbers in comparable European countries.

The Polities of Envy

If I were asked to assign reasons for this, I would place first the fact that for nearly thirty years the policies of the left wing parties in this country have been based on the politics of envy. People have been taught to believe that the interest of the workforce is necessarily adverse to that of management or the shareholder, that the middle and professional classes deserve to be driven into the ground if the worker is to have his due, and that there is something inherently dishonourable and undemocratic in success and effort, indeed in distinction of any kind. It is intelligible, if manifestly mistaken, for Marxists to believe all this, since it is part of their philosophy to destroy the existing order of things altogether. But for Social Democrats to believe it or have truck with it in any way is treason to everything they stand for and to the cause of liberty itself. In contrast to our own leftists, the peoples of the European continent, under the impact of calamity and defeat, have been taught to believe that the interests of all classes within a national society are ultimately the same, and that more can be got for all by working together than by the politics of envy or the philosophy of egalitarianism. But the policies of envy pursued so steadfastly on the left are not limited to home affairs. It seems impossible to persuade a large section of the Labour Party that economic isolation, which they mistake for national independence and sovereignty, is not possible for a nation which wishes to export, or which needs to borrow money from time to time in order to prevent a run on its currency. Net borrowers are never independent, and exporters who will not receive imports invariably provoke retaliation. The economic chauvinism of the Labour Party has successively delayed our membership of the Common Market and made our membership of it less acceptable. Of all nations in the world we stand to gain the most by the application of new inventions at home and international economic co-operation abroad. Yet our record at home has been to clobber enterprise, and abroad to distrust and delay co-operation.

So, if I am asked where we are going, I say sadly that at present we are going downhill. But I add that the remedy is in our own hands. We need to take a leaf out of the book of our more successful competitors. •

Previous page

Previous page