WHAT HOPE FOR THE DECENT SOCIETY?

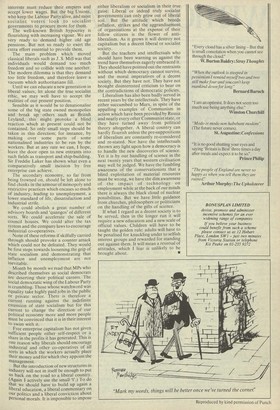

Rt. Hon. Jo Grimond former leader of the Liberal Party sees a strong tide driving us towards autocracy.

Conventional punditry often describes Britain as a decent if unsuccessful country—we have lost an empire, found no role, are far down the league table of economic growth, yet we are kindly, caring, foreigners like coming here—you know all the cliches.

In reality we are a complacent if fairly comfortable country. Decency may survive but it is being eroded. The morals of many strikers are those of kidnappers. "If you don't pay up we will torture or kill your child" say the kidnappers. "If you don't pay up we will see that hospital patients suffer" say the hospital workers. And both, of course, shed crocodile tears for their victims but press their claims by means which must destroy any decent society.

However, measured by the ownership of cars, television sets, washing machines, etc. we are better off than we were and few people today starve or go barefoot.

We are ceasing to be a liberal (with a small T) country but are not becoming a socialist (with a small 's') country. Both these political faiths require ethics which, though they still command lip service, are decreasingly put into practice in Britain. Liberalism demands that we see individuals as the depositary of all values.

Therefore we must cherish individual freedom which in turn entails constant individual responsibility and judgement. The tyranny of the majority has long been seen by liberals as the enemy of freedom. Take one example—the closed shop: this is not only an indefensible inroad on freedom but it is often defended on the ground that a majority of those employed voted for it, thereby adding insult to injury. Liberalism demands a respect for one's neighbours and an interest in their well-being. Today individuals justify doing things which they know to be wrong, by pleading that they are bound to fall in with the orders of their superiors or their Unions. True socialism holds that aggression, prestige-seeking, acquisitiveness must and can be replaced by turning of the other cheek, humility and readiness to forego great possessions. But today's socialist organisations hardly hold to this faith.

These developments may dismay us but they should not surprise us. To run a country according to liberal beliefs is a difficult operation which has seldom been attempted for long. Some form of autocracy is much more common. The competing claims of different interest groups in this country are comparable to the ambitions of the barons in feudal times. Those barons were eventually brought under control by increasing the power of the Crown.

Where then do we go from here? If I were a detached spectator asked to bet on the future like a punter at a race meeting I should say that inflation will increase until we accept autocratic rule as the only way to cure it. The autocracy may not be severe: but under it we shall go the way of Austria or Spain in the last century. Already state control increases. We are more and more regimented. Even the Liberal Party advocates a compulsory income and prices policy. The Welfare Services themselves are changing from being a means of helping the poor into becoming a general method of state intervention with some six million people in receipt of assistance.

But I am not a disinterested spectator. I firmly believe in liberalism. What then can be done? We must face the difficulties if we are to reverse the trend. First, there are internal contradictions in liberalism and idealistic socialism as guides for government.

Liberalism demands that government should be kept to a minimum. But liberal politicians and non-socialist parties must justify themselves by promising that if returned to government they will pass more legislation. Take the present position: it would be sensible if Parliament were to make no new laws in this session. But would such an announcement be welcomed? I am afraid not. As for socialists; socialists interested in equality and the elimination of greed should be proclaiming that some large vested interests must reduce their empires and accept lower wages. But the big Unions, who keep the Labour Party alive, and most socialist voters look to socialist governments to procure more for them. The well-known British hypocrisy is flourishing with increasing vigour. We are very ready to demand higher old age pensions. But not so ready to exert the extra effort essential to provide them.

The main problem which moved classical liberals such as J. S. Mill was that individuals would demand too much freedom and so collide with one another. The modern dilemma is that they demand too little freedom, and therefore leave a vacuum which authoritatians fill.

Until we can educate a new generation in liberal values, let alone the true socialist ethic, we may well have to accept the realities of our present position.

Sensible as it would be to denationalise some of the big state owned monopolies and break up others such as British Leyland, this might provoke a blind reaction which at present could not be contained. So only small steps should be taken in this direction; for instance, by making over some parts of some nationalised industries to be run by the workers. But at any rate we can, I hope, leave the door open to new entrants into such fields as transport and ship-building. Sir Freddie Laker has shown what even a comparatively small incision by free enterprise can achieve.

The secondary economy, so far from being frowned on, should be left alone to find chinks in the armour of monopoly and restrictive practices which encases so much of industry, leading to unemployment, a lower standard of life, dissatisfaction and industrial strife.

We could abolish a great number of advisory boards and `quangos' of different sorts. We could accelerate the sale of council houses. We could alter the tax system and the company laws to encourage industrial co-operatives.

None of these reforms if skilfully carried through should provoke a counter attack which could not be defeated. They would be first steps towards loosening the grip of state socialism and demonstrating that inflation and unemployment are not Inevitable.

Month by month we read that MPs who described themselves as social democrats are deserting their political careers. The social democratic wing of the Labour Party is crumbling. Those whose watchword was equality take highly paid jobs in the public or private sector. There is therefore. a current running against the indefinite extension of state socialism but for this current to change the direction of our Political economy more and more people must be convinced that it is in their interest to swim with it.

Free enterprise capitalism has not given sufficient people either self-respect or a share in the profits it has generated. This is one reason why liberals should encourage industrial and other co-operatives of all sorts in which the workers actually place their money and for which they appoint the management. But the introduction of new structures in Industry will not in itself be enough to put us back on the road to a liberal country. (Again I actively use the small T.) To do that we should have to build up again a liberal education, a liberal commentary on our politics and a liberal conviction about personal morals. It is impossible to impose either liberalism or socialism in their true guise. Liberal or indeed truly socialist governments can only grow out of liberal soil. But the attitude which breeds inflation, strikes and the aggrandisement of organisations at the expense of their fellow citizens is the flower of antiliberalism. As it grows it will destroy not capitalism but a decent liberal or socialist society.

But the teachers and intellectuals who should have been warning us against the trend have themselves eagerly embraced it. They should have pointed out the restraints without which democracy cannot survive, and the moral imperatives of a decent society. But they have not. They have not brought disinterested criticism to bear on the contradictions of democratic policies.

Liberalism has also been badly served in recent years by the intellectuals. They have either succumbed to Marx, in spite of the appalling examples of Communism in action which have been provided by Russia and nearly every other Communist state, or they have turned away from political theory altogether. A liberal country can hardly flourish unless the pre-suppositions of liberalism are constantly re-considered and re-stated. Nor have the intellectuals thrown any light upon how a democracy is to handle the new discoveries of science. Yet it is by our handling of science in the next twenty years that western civilisation may well be judged. We have the fumbling awareness of the conservationists that a blind exploitation of material resources must be wrong, we have the dim awareness of the impact of technology on employment while at the back of our minds there is always the black cloud of nuclear possibilities. But we have little guidance from churches, philosophers or politicians on the handling of the gifts of science. If what I regard as a decent society is to be served, then in the longer run it will require a new education and a new scale of official values. Children will have to be taught the golden rule: adults will have to be penalised for knuckling under to selfish interest groups and rewarded for standing out against them. It will mean a reversal of attitudes, which I fear is unlikely to be brought about. •

Previous page

Previous page