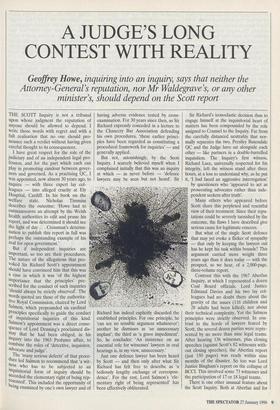

A JUDGE'S LONG CONTEST WITH REALITY

Geoffrey Howe, inquiring into an inquiry, says that neither the

Attorney-General's reputation, nor Mr Waldegrave's, or any other minister's, should depend on the Scott report

THE SCOTT Inquiry is not a tribunal upon whose judgment the reputation of anyone should be allowed to depend. I write those words with regret and with a full realisation that no one should pro- nounce such a verdict without having given careful thought to its consequences.

I have great respect for the role of the judiciary and of an independent legal pro- fession, and for the part which each can Play in promoting candour between gover- nors and governed. As a practising QC, I was appointed, now almost 30 years ago, to inquire — with three expert lay col- leagues — into alleged cruelty at Ely Hospital, Cardiff. In his book on the welfare state, Nicholas Timmins describes the outcome: 'Howe had to outmanoeuvre an attempt by the Welsh health authorities to edit and prune his report, and was determined it should see the light of day . . . Crossman's determi- nation to publish this report in full was Perhaps the outstanding example of his zeal for open government.'

But if independent inquiries are Important, so too are their procedures. The nature of the allegations that pro- voked Sir Richard Scott's appointment should have convinced him that this was a case in which it was 'of the highest Importance that the principles' pre- scribed for the conduct of such inquiries `should always be strictly observed'. The words quoted are those of the authorita- tive Royal Commission, chaired by Lord Salmon, which propounded six cardinal principles specifically to guide the conduct of inquisitorial inquiries of this kind. Salmon's appointment was a direct conse- quence of Lord Denning's proclaimed dis- may that he had been obliged, in his Inquiry into the 1963 Profumo affair, to combine the roles of 'detective, inquisitor, advocate and judge'. The 'many serious defects' of that proce- dure led Salmon to recommend that 'a wit- ness who has to be subjected to an Inquisitorial form of inquiry should be accorded the elementary right of being rep- ,resented'. This included the opportunity of Doing examined by one's own lawyer and of having adverse evidence tested by cross- examination. For 30 years since then, as Sir Richard expressly conceded in a lecture to the Chancery Bar Association defending his own procedures, 'these earlier princi- ples have been regarded as constituting a procedural framework for inquiries' — and generally applied.

But not, astonishingly, by the Scott Inquiry. I scarcely believed myself when I complained initially that this was an inquiry at which — as never before — 'defence lawyers may be seen but not heard'. Sir Richard has indeed explicitly discarded the established principles. For one principle, he `can see no sensible argument whatsoever'; another he dismisses as 'an unnecessary implant'; the third as 'a grave impediment'. So, he concludes: 'An insistence on an essential role for witnesses' lawyers in oral hearings is, in my view, unnecessary.'

Just one defence lawyer has been heard by Scott — and then only after what Sir Richard has felt free to describe as 'a tediously lengthy exchange of correspon- dence'. For the rest, Lord Salmon's 'ele- mentary right of being represented' has been effectively obliterated. Sir Richard's iconoclastic decision thus to engage himself at the inquisitorial heart of matters has been compounded by the role assigned to Counsel to the Inquiry. Far from the carefully distanced neutrality that nor- mally separates the two, Presiley Baxendale QC and the Judge have sat alongside each other — like partners in a double-barrelled inquisition. The Inquiry's first witness, Richard Luce, universally respected for his integrity, left the witness stand after three hours, at a loss to understand why, as he put it, 'I had faced an aggressive interrogation' by questioners who 'appeared to act as prosecuting advocates rather than inde- pendent seekers after truth'.

Many others who appeared before Scott share this perplexed and resentful view of their treatment. Since their repu- tations could be severely tarnished by the outcome, the flaws I have described give serious cause for legitimate concern.

But what of the single Scott defence that may yet evoke a flicker of sympathy — that only by keeping the lawyers out has he kept his task within bounds? This argument carried more weight three years ago than it does today — with the prospect, so we hear, of a 2,000-page, three-volume report.

Contrast this with the 1967 Aberfan Inquiry, at which I represented a dozen Coal Board officials. Lord Justice Edmund Davies and his two lay col- leagues had no doubt there about the gravity of the issues (116 children and 28 adults had been killed), nor about their technical complexity. Yet the Salmon principles were strictly observed. In con- trast to the horde of lawyers feared by Scott, the several dozen parties were repre- sented by no more than nine legal teams. After hearing 136 witnesses, plus closing speeches (against Scott's 82 witnesses with- out closing speeches), the Aberfan report (just 150 pages) was ready within nine months of the disaster. So too was Lord Justice Bingham's report on the collapse of BCCI. This involved some 73 witnesses and the participation of 17 or 18 legal teams.

There is one other unusual feature about the Scott Inquiry. Both at Aberfan and for BCCI the judge had the assistance of expert lay assessors. This is the usual pattern. Lord Justice Bingham has emphasised the value of such help. 'Drawing on their experience and expertise,' he said, 'they have contributed invaluable insights and guidance.'

Particularly in the absence of any expert lay colleagues, Sir Richard's determination to deprive himself of the interchanges which would normally have taken place with advocates appearing on behalf of key witnesses substantially increased the length of the Inquiry, as his handling of one ques- tion makes clear.

I have in mind his discussion of the validity of the export control legislation which found- ed the Matrix Churchill prosecutions. This 1939 Act, enacted at emergency speed, was short and simple: Government was empow- ered to make statutory instruments, defining the scope of export controls, without any provision for formal parliamentary oversight of those orders. Six times between 1952 and 1986 Parliament, without any dissent, autho- rised the continuance of these powers. They had caused no trouble. 'If it works,' thought Parliament, 'don't fix it.'

In 1990 Iraq invaded Kuwait. The contin- uing need for this well-tested legislation was underlined. To entrench its continuing validity, we were advised to introduce a brief bill, removing the 'emergency' back- ground of the 1939 Act. The Opposition readily agreed to this endorsement of a sys- tem that had worked well for a half a cen- tury. So, without dissent in either House, the 1990 Act was passed. Defence counsel in the Matrix Churchill trial did not chal- lenge any of the legislation.

But Sir Richard felt the need to 'maximise the opportunity for public debate' of this question and circulated a discussion paper to that end. In his subsequent appraisal of the subject, which was laced with such phrases as `failure both of Government and of Opposi- tion', and 'totalitarian in concept and effect', Sir Richard concluded that Government's continued exercise for about 45 years of the powers conferred by the 1939 Act was 'a continuing abuse of power'.

This was certainly a much broader target than any misdeeds of the Major, or even the Thatcher, administration! Even so, it would be a disquieting observation, if allowed to stand. Happily, it was not the last word — or at least it ought not to be.

For since Sir Richard first recorded that view, the Court of Appeal has considered the very same question, in the Ordtec case (also involving exports to Iraq). Defence counsel in that case had been alerted to Sir Richard's propositions and given leave to argue them before the Lord Chief Justice and two colleagues. The hearing lasted just one day. Later, expressing the Court's unani- mous conclusion, the Lord Chief Justice roundly rejected Sir Richard's conclusion: `In our judgment the 1939 Act has remained in force and it was lawful to exer- cise the powers under it . . . The alternative argument that . . . successive Governments abused their powers . . . is in our view unsustainable.'

It remains to be seen whether the final Scott text reflects this judgment, or whether Sir Richard's earlier 'opinions' remain in place, in support of the gratu- itous conclusion that 'the constitution has become an elective dictatorship'.

If Sir Richard had at the outset been able to raise his query direct with Counsel, he could soon have heard for himself the points that later impressed the Lord Chief Justice. The mountainous exchange of papers need never have happened. The wild goose could soon have been identified as the dead duck that it turns out to be.

This episode illustrates Sir Richard's approach to his task. A disposition to chal- lenge convention, to defy precedent, to pre- sent issues in black-and-white terms has been matched by tenacious enthusiasm for his own views. These are scarcely the ideal qualifica- tions for the task of judging how well the var- ious specialists involved in the Matrix Churchill/Ordtec saga succeeded in striking a proper balance between competing British interests. For that was their only objective.

That is the point to understand. This is a story in which there are no villains. British policy was in principle almost sanctimo- niously virtuous. Almost alone among the industrial nations, we had banned the sup- ply of 'defence-related equipment' to Iran and Iraq alike. From one or other of our competitors — the Soviet Union or Ger- many, China or France — these weapons were always available. Not from Britain. Sir Robin Butler's evidence, that 'no licences for the export of arms, that is lethal goads, were issued by the British Government', has never been challenged. This is why `arms-to-Iraq' is such a misnomer for the Scott Inquiry itself.

Yet we were rightly anxious for British business to maintain legitimate trade with both sides. The entire controversy arises over the policing of this borderline — in the grey area of so-called 'dual-use equipment'. Paul Henderson and his fellow directors found themselves being prosecuted by Customs and Excise for supplying machine tools to Iraq at a time when the various agencies of government had no complete idea what others were up to. The answer may only emerge after analysis of detailed evidence about contacts between officials.

But that is not the question that excites interest. What scalp-hunting commentators want to know is whether any minister is to be found guilty of allowing Henderson and his fellow directors to be prosecuted unfairly. The name of one minister has been promi- nent ever since the trial collapsed. Alan Clark may well have been less than fully Informed about Paul Henderson's intelli- gence role. But he did know about his own attitude towards the trade for which Hender- son has been prosecuted. For Clark had, by his own admission, given a nod and a wink to such transactions, not for intelligence reasons, but because he wanted to see trade expand. Had Alan Clark made that plain in his original witness statement, the case would never been brought.

There is only one other minister who could theoretically be criticised on this point and that is the Attorney-General, Sir Nicholas Lyell. This was a case which most unusually and with considerable pru- dence — he did call in for personal review before it proceeded to trial. He was then assured by very experienced prosecuting counsel that it was in order to proceed, subject to the necessary clarification of Alan Clark's evidence. When that had seemingly been achieved (for Clark was still then being economical with the truth), there was no possible reason for the Attor- ney-General to stop the prosecution.

Sir Nicholas had one other responsibility — namely to advise fellow ministers about the extent of their duty to sign Public Inter- est Immunity Certificates, so as to oblige the Court to decide whether or not certain documents should be disclosed to the defence. The law on this is long-established, and made not by Parliament but by the judges. It is not intended, nor has it been used, `to save politicians' skins', or to 'gag witnesses', but because of the (judge- defined) public interest in saving from dis- closure certain documents which ought to remain confidential. Ministers were — at the time of this case — under a clear duty to claim such immunity. Then it was, again by law, a matter for the trial judge, after examining the documents, to decide whether the interests of justice in securing a fair trial outweighed the public interest in confidentiality identified in the Certificates.

This is exactly what happened here. As counsel for the defence of one of Paul Hen- derson's colleagues said in a letter to the Times, a few days after the trial: 'The judge decided in favour of disclosure and the documents were immediately produced.' This helped to found the cross-examination that led to Alan Clark's devastating admis- sion and so the collapse of the trial. The approach of the Crown to the question of Public Interest Immunity, said defence counsel, was thus 'entirely in accordance with our understanding of the decided cases'. In these circumstances, it is unlikely that even Sir Richard Scott can find a way of criticising any of the ministers — from Michael Heseltine to Tristan Garel-Jones — who, following the Attorney-General's advice, signed PII certificates in the Matrix-Churchill case.

It remains to be seen whether Sir Richard will be willing, as he should be, to give simi- lar clearance to the Attorney-General. This is an area where the case for reforming the law can plausibly be argued. Indeed the House of Lords, in a recent decision, has already effected some changes. To judge by his observations when Sir Nicholas Lyell was giving evidence, Sir Richard Scott would like to propose some other reforms.

He is, of course, entirely free to make such recommendations for the future. But what he would not be entitled to do is to judge the correctness of the Attorney- General's earlier advice and actions by any- thing but the law as it was and was under- stood to be at that time. There is no room for doubt that the Attorney-General's advice to ministers was, as defence counsel told the Times, entirely in line with the gen- eral understanding of the then law. He was, moreover, specifically supported by advice from experienced Treasury Counsel.

If Sir Richard Scott concludes that those established views on which Sir Nicholas Lyell rightly based his advice should be treated in the same cavalier fashion he has displayed towards the opinions and judg- ments of Lord Salmon and Lord Chief Jus- tice Taylor on the points already discussed, then neither the Attorney-General nor any- one else should be condemned for their conduct — nor even unduly troubled by such idiosyncratic conclusions.

Exactly the same gap of non-comprehen- sion, between the solitary Scott and the real world, arises on the other main question on his agenda: were ministers separately and collectively — and consistently over a period of five or six years — guilty of 'misleading Parliament'? For the sake of journalistic sim- plification, this question has increasingly and quite unjustly — been focused on William Waldegrave. This makes it no doubt more exciting for those who regard Scott as a spectator sport and want only to know whose `heads are to roll'.

But if Waldegrave is to be condemned in this way, then so should be every minister concerned with this question before, during and after the _Iran-Iraq war. This includes Richard Luce, who (way back in 1984) had initially been in favour of immediate publi- cation of the original Howe Guidelines, but who was, quite rightly, persuaded that, in order to avoid damage to British interests elsewhere in the Gulf, they should be allowed to 'trickle out' later. So too it includes Margaret Thatcher, Douglas Hurd and a host of others including myself, who to the end were answering Parliamentary Questions with the traditional formula that `it has been the practice of successive administrations not to comment on matters of this kind', or words to that effect.

Sir Richard Scott, with characteristically scathing zeal, has so far dismissed this entire case as 'sophistry'. He appears to view the claim to confidentiality as no more than a convenient excuse to avoid political embarrassment. There has been, in his view, 'a consistent undervaluing by Govern- ment of the public interest that information should be made available to Parliament'.

Yet, as we have tried to point out to Sir Richard a thousand times, Parliament and the courts have consistently respected the need for those responsible for the conduct of foreign, diplomatic and economic affairs to safeguard a wide range of information from the many hostile or competing nations, institutions and individuals around the world, whose principal interests may well include doing damage to, competing against or otherwise outwitting the inter- ests of our own country.

It is — or should be — a matter of com- mon sense that in these circumstances the processes of government cannot be conduct- ed in a goldfish bowl. Publication to Parlia- ment is the same as publication to the world. It is for this reason that the United States Freedom of Information Act, 1974, expressly exempts from disclosure information requir- ing protection in the interest not just of defence but of foreign relations more gener- ally. So too in Canada, Germany, the Netherlands and throughout Scandinavia; in France, of course, no one would even dream of asking the question.

The elementary wisdom of this analysis has been widely recognised. Sir David Steel, for example, when he was first told, in an answer from me, of the original 1984 guidelines, only after a delay of nine months since their adoption, expressed no surprise, still less shock or dismay. At no time, indeed, has any Opposition parlia- mentarian criticised the degree of confi- dentiality that, like ministers in all previous governments, we consistently upheld. This is, of course, only one more reason why it is so regrettable that Sir Richard did not have the benefit of any independent assessors to help him in his judgment of such questions.

So any criticism by the Scott Inquiry of William Waldegrave (or anyone else) for lack of candour would be wholly without jus- tification, not just by the standards universal- ly adopted at the time but by any reasonable standards of the art of government. William Waldegrave will be entitled to expect noth- ing but robust defence of his position on this issue, not just from his colleagues in govern- ment, but from anyone who can still take a balanced view of this profoundly practical question.

One further matter remains, the bone which Sir Richard has relished chewing throughout the last three-and-a-half years. Did William Waldegrave, Alan Clark and David Trefgarne (Minister of State, first at Defence, later at Trade and Industry) agree, early in 1989 (and after the Iran/Iraq shoot- ing war had ended), to 'change' my 1984 Guidelines, and yet wickedly conspire to conceal this fact from their superiors, from Parliament and from the wider world? Or was there no more than a series of variations in the application or interpretation of the original Guidelines?

I've put the cat out.' There are two reasonably compact answers to this question. The first is the clear evidence of the ministers and most of the officials concerned that in their own minds they had certainly not 'changed' the Guide- lines. And the second is that in July 1990 shortly before Iraq invaded Kuwait — a meeting of ministers under the chairmanship of the Foreign Secretary, Douglas Hurd, had to consider this topic. They concluded as fol- lows: The 1985 Guidelines . . . now needed to be revised in light of changed circum- stances.' The continuing existence of the unamended 1985 Guidelines was expressly presented and accepted as the unquestioned premise of that discussion amongst fully briefed ministers. This surely calls into ques- tion Sir Richard Scott's persistent belief that 15 months earlier, in the spring of 1989, the Guidelines had in fact been amended by William Waldegrave and his ministerial col- legues, Trefgarne and Clark.

Probably the most serious risk of the entire Inquiry is that Sir Richard — per- haps understandably, even if unconsciously, anxious to score at least some goals in his marathon contest with reality — will not only stick to his own view but may do so in terms that will imply dishonesty on the part of one or other or even all of the many who have presented him with the opposite arguments.

That would be a travesty of justice. The fact that William Waldegrave's view of the facts was widely shared amongst ministers and officials is sufficient to show that unless they had all agreed to pretend to believe something which they did not, that collective view was honestly held. The opposite sugges- tion of concerted dishonesty has never been put by or on behalf of Scott to any witness. The Inquiry should, therefore, accept the widely and honestly shared view.

If Sir Richard proves as willing to dismiss the integrity of ministers as he has been to discount the views of Lord Salmon and the Lord Chief Justice, to accuse Government of 'abuse of power' over 40 years, and to criticise the Attorney-General for having applied the law exactly as he had been advised to do, then one must conclude that it will be the Inquiry itself and not its vic- tims which will have to be set to one side.

Lord Justice Edmund Davies and his lay colleagues took nine months and 150 pages to investigate the catastrophe at Aberfan. Sir Richard Scott looks like having taken almost five times as long and more than 13 times as many pages to consider the circumstances in which three businessmen came to be prose- cuted — and finally acquitted. That simple comparison may say a good deal about the sense of proportion and quality of judgment of the forthcoming Inquiry report.

Lord Howe of Aberavon, QC, was Solicitor- General 1970-72, Chancellor of the Exche- quer 1979-83, Foreign Secretary 1983-89 and Deputy Prime Minister 1989-90, cover- ing the years being investigated by the Scott Inquiry.

Previous page

Previous page