REVIEW OF BOOKS

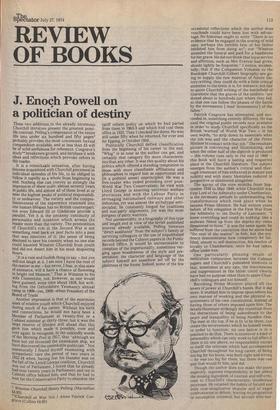

J. Enoch Powell on a politician of destiny

These two additions to the already enormous Churchill literature present the greatest possible contrast. Pe!ling's compression of the entire life into under six hundred and fifty pages* Probably provides the most convenient factual compendium available, and at less than £5 will be of solid usefulness for reference. Cosgrave's study**breaksnew ground, and fertilises it with ideas and reflections which provoke others in the reader.

It is a remarkable sensation, after having become acquainted with Churchill piecemeal in individual episodes of his life, to be obliged to follow it rapidly as a whole from beginning to end. Nothing else can convey so strongly the Impression of sheer scale: almost seventy years in public life, and almost all of them lived at or near the highest peaks of political responsibility or endeavour. The variety and the comprehensiveness of the experience crammed into one human lifespan has no British counterpart: not even Edward III or Gladstone provide a Parallel. Yet it is the uncanny continuity of Personality and intention which arrests the reader more than the variety. The premonition of Churchill's role in the Second War is not something read back ex post facto into a past that was innocent of it: the sense of being destined to save his country when no one else could haunted Winston Churchill from youth and did not desert him in his most despairing hours.

"It is a vain and foolish thing to ay — but you Will not laugh at it. I am sure I have the root of the matter in me — but never, I fear, in this state of existence, will it have a chance of flowering in bright red blossom." That is Winston to his Wife Clementine, not, however, as one would have guessed, some time about 1938, but writing from the Oxfordshire Yeomanry annual camp in 1909—yes, 1909—when President of the Board of Trade.

Another impression is that of the enormous asset of relative youth which Churchill enjoyed during much of his career. Without his birth and connections, he would not have been a Member of Parliament at twenty-five or a Cabinet minister at thirty-three; but it was the large reserve of lifetime still ahead that this gave him which made it possible, over and over again, to recognise, in the unkindly words Of the Morning Post in 1917, that "although we have not yet invented the unsinkable ship, we have discovered the unsinkable politician." Not unnaturally I found myself examining with sympathetic care the period of two years in 1922-24 when, having lost his Dundee seat on the fall of the Lloyd George coalition, Churchill was out of Parliament. 1 noted that he already had over twenty years in Parliament and ten in Cabinet office behind him, and that he had to wait for the Conservative Party to abandon the * Winston Churchill Henry Pelling (Macmillan E4.95) **Churchill at War Vol. 1 Alone Patrick' Cosgrave (Collins £4.95)

tariff reform policy on which he had parted from them in 1903-5 and which had cost them office in 1923. Then I checked the dates. He was still under fifty when he returned, for ever and for Epping, in October 1924. Politically Churchill defied classification from the beginning of his career to the end. "Whig" is as near as the. author can get, and certainly that category fits more characteristics than any other. It was this quality about his politics which offered a standing temptation to those with more classifiable affiliations and philosophies to regard him as opportunist and (in a political sense) unprincipled. He was a free-trader who ended presiding over postWorld War Two Conservatism; he vied with Lloyd George in enacting universal welfare provisions and with the Labour Party in envisaging nationalised railways and other industries, yet was almost the archetypal antisocialist; he constantly longed for coalitions and non-party alignments, yet was the most pungent of party warriors. Not unreasonably, in a biography of this type and length and in view of the lavish published sources already available, Pelling forswore "direct assistance" from the subject's family or surviving colleagues or the use of unpublished records beyond the Cabinet papers in the Public Record Office. It would be unreasonable to complain of the impersonality, sometimes verging upon woodenness of the style and presentation: the character and language of the subject himself are somehow set off by the plainness of the frame. Indeed, some of the few occasional reflections which the author does vouchsafe could have been lost with advan tage. No historian ought to write "There is no evidence that he engaged in the sowing of wild oats: perhaps the terrible fate of his father inhibited him from doing so"; nor "Winston attended the funeral and paid for a headstone for her grave. He did not think that loyal service and affection, such as Mrs Everest had given, should lightly be forgotten." I notice, incidentally, that if the Companion Volumes to the Randolph Churchill/Gilbert biography are going to supply the raw material of future history-writing, they could do with a little critical attention to the texts: it is, for instance, not fair to quote Churchill writing of the battlefield of Gravelotte that the graves of the soldiers "are dotted about in hundreds just where they fell, so that one can follow the phases of the battle by the movements [ read 'monuments] of the fallen."

Patrick Cosgrave has attempted, and succeeded in, something entirely different. He has used the original public records now available in order to study Churchill specifically as the British 'warlord' of World War Two — in his own words, "to strip down to essentials what the job was and the character of the Prime Minister in contact with that job." The resultant picture is convincing and illuminating, and when the other half of the diptych is produced — this volume runs only to the end of 1940 — this book will have a lasting and respected place in the Churchill literature. The subject emerges from the author's critical and thorough treatment of him enhanced in stature and nobility and with many blemishes reduced in perspective or eliminated altogether.

The agony of the nine months from September 1939 to May 1940, while Churchill was First Lord of the Admiralty under Chamberlain, is the necessary prelude to understanding the transformation which took place when he became Prime Minister. He had written years before, of his relegation in the First War from the Admiralty to the Duchy of Lancaster, "I knew everything and could do nothing: like a seabeast fished up from the depths my veins. threatened to burst." It was the same again: he suffered from the conviction that he alone had "the root of the matter" in him, but the evidence demonstrates how completely he fulfilled, almost to self-destruction, his resolve of loyalty to Chamberlain, once he had taken office under him.

One particularly pleasing result of • meticulous comparison between the Cabinet papers and Churchill's published memoirs is that, sometimes at any rate, the inaccuracies and suppressions in the latter could clearly . have had no purpose other than to spare Churchill's colleagues and not himself.

Becoming Prime Minister placed all the levers of power at Churchill's hands. But it did more. It enabled him to impose upon others his own manner of working and the physical requirements of his own constitution, instead of having those of others imposed upon him. The details illuminate strikingly the transition from the distractions of being subordinate to the peace and tranquillity of being Number One. The man at the top, if he is fit to be there, can create the environment which he himself needs in order to function: no one below is in a position to do that. There is moreover a kind of personality which can only work to full effect if there is no one above, no responsibility except to itself: the criticism which had accompanied Churchill throughout his long career, of being too big for his boots, was both right and wrong — he was too big for them, but there was one pair that would fit him, and did. Though the author does not make the point explicitly, supreme responsibility at last added the missing ingredient of caution and self-criticism to Churchill's characteristic intellectual processes. He retained the habits of fecund and even over-imaginative impulse and of eager confrontation in debate, leaving no proposition or assumption untested; but anyone who nur tures the common notion of Winston as prime minister committing effort and forces to rash and illogical purposes in the teeth of professional advice will be forced by the evidence in this book to replace that picture with a very different one. He will find a Churchill whose impatience and dynamism had found their counterpoise in cautious and measured decision-taking. The crucial episodes of the decisions to cover the evacuation from Dunkirk, to terminate the transfer of British fighter squadrons to France, to neutralise or destroy the French navy, emerge substantially clarified from a narrative for which the Cabinet and other official minutes furnish the central core.

Even the most meticulously chronological history, if it is to be history at all, is obliged from time to time to 'double back.' The course of events running from the German breakthrough in Northern France to the termination of the 'Battle of Britain' is a seamless garment and had to be followed consecutively. What comes as almost a.shock is to be forced by later chapters to recognise how, during the actual progress of that crucial struggle, the Prime Minister and the War Cabinet were taking decisions, and applying strenuous pressures, in directions which determined the military capability of Britain on D-Day in 1944, the outcome of the war in the Mediterranean and the Middle East, and even, to some extent, the effort that would be mounted against the Japanese attack. The moral and intellectual unity of the British war effort is demonstrated by the documentary evidence to have been actually, as it was in outward appearance, vested in the person and personality of the Prime Minister. The British parliamentary and Cabinet system of government, developed for checking and balancing governments and interests in peacetime, revealed itself as incomparably flexible and efficient for the purposes of a national war, once the nerve-centre of the Prime Ministerial.office was occupied, as it turned out to be, by the requisite combination of political and military will and capability.

Mr Cosgrave was born too recently to participate as an adult in the war which his subject dominated. He was not, by training or profession, baptised into the armed forces, even in peace. He has written a book which, quite apart from its critical and historical competence and insight, is imbued — as it appears instinctively — with the authentic sense of a nation in arms in defence of its existence. I thought to myself, when I reached the end, "So long as a generation can understand Churchill at War, it will know what to do when its own time comes."

The Rt Hon J. Enoch Powell was formerly Conservative MP for Wolverhampton SouthWest.

Previous page

Previous page