FINE ARTS SPECIAL

Leave our museums alone

Martin Gayford on why government-sponsored populism just isn't popular Every cliché eventually meets its neme- sis. Sooner or later — in fact quite often more haste actually means more speed. i Certain winds really do turn out so ill they blow nobody any good. And, in the last few i months, we've seen it happen: someone is shpwlY going bust by underestimating the taste of the public. Or if the Millennium Dome isn't bust yet, it's getting extremely Close. Meanwhile, of course, Tate Modern has turned out to be startlingly, even slight- ly alarmingly popular, with more than 3°,000 people a day entering its mighty Turbine Hall. What can be deduced from these phenomena? Clearly, one point that emerges from 8.1101 projects is the huge advantage of hav- ing the whole thing driven through by one pe.rson of vision. Tate Modern is Sir Nicholas Serota's achievement. He thought of it, he masterminded it. He deserves and, I am glad to see, is receiving — our gatitude and admiration. In contrast, the ,.°11le was a muddled project from begin- ,"ing to end. Nobody ever knew what it was supposed to be or do, except be popular, and It was put together by committee. bP,.,ne of the artists involved, represented "11 at Greenwich and Bankside, !remarked the other day that no such pro- lect should ever again be run by the gov- Tiolent. Perhaps. Though democracy is doubtless best for politics, there's not much doubt that dictatorship is best in the arts. s'ull the other hand, large projects can be ,_ecessfully driven through by government Papal as they were in Mitterrand's Paris, .and tk. Rome for that matter — provided nett is a single, controlling hand. What is absolutely plain, however, is that government-sponsored populism just isn't popular. And this has wider implications for museum policy. In the Dome we have an improving, politically correct theme park. With the benefit of hindsight it's obvious that wouldn't be a wow, and even in advance many foresaw problems. If you want to go to a theme park, you go to Alton Towers.

But pressures for unpopular populism remain. In January Matthew Evans, the incoming chairman of the new Museums, Libraries and Archives Commission, gave a notorious address (he took up the post at the beginning of last month). The speech left no New Labour button unpressed. Museums, he asserted, must 'become rele- vant to the politicians and to the millions of ordinary people who not only directly and indirectly fund us but are our customers'. They must 'modernise' and 'reinvent them- selves', they must take their collections into shops and pubs, otherwise they risked becoming cultural versions of Marks & Spencer — 'symbols of once great institu- tions that failed to move with the times and are now suffering as a result'.

To say that these sentiments went down badly would be a huge understatement. Very fairly, and under the circumstances mildly, Brian Sewell described the speech as 'the thoughts of Chairman Mao couched in the conventional waffle of Islington'. Richard Dorment observed that 'most peo- ple who heard or read his lecture have con- cluded that he has only the vaguest idea what museums are for, how they function, and what is actually happening today'.

Among other points, museums and gal- leries already have embraced new technol- ogy, they already have banks of computer terminals and websites (though whether these do much good is another question: the essential experience museums and gal- leries have to offer is confrontation with the real thing).

Furthermore, the best London museums already are phenomenally popular. Any more visitors at Tate Modem and there would be a risk of suffocation. The same is also true at the National Gallery, the British Museum, the National Portrait Gallery and Tate Britain on Millbank. Where on earth are those 'new audiences' Lord Evans insists must be developed going to fit? It is those museums which have attempted to take the populist course and — perhaps most to the point — those which have introduced admission charges that have seen attendance drop.

Perhaps, in the light of the experience of the last couple of weeks, one can now go a little further than Sewell and Dorment. Evans was giving voice to an attitude towards museums which has been preva- lent in bureaucratic circles for a long time, not only under this government but also under the last — an approach which can now be seen as philistine, condescending and utterly, demonstrably wrong-headed.

In a paper a couple of years ago Charles Saumarez Smith, director of the National Portrait Gallery, remarked that in the past two decades 'the two original purposes of museums — as collections of artefacts and as research institutions — have either been at war with, or been replaced by, two new purposes'.

The first is as an educational resource. The annual visitation from the members of the Department for Culture, Media and Sport is an occasion, Saumarez Smith relates, 'when half a dozen men in grey suits troop through the Gallery looking bored until they come to the areas devoted to educational activities'. At that point, `their eyes light up as they see something of which they hope their ministers will approve'. The second is as a leisure attrac- tion. To see what the public really thinks about this double agenda, observe the fate of the Dome, educational leisure attrac- tion. Museums and galleries, in any case, should aim to be neither.

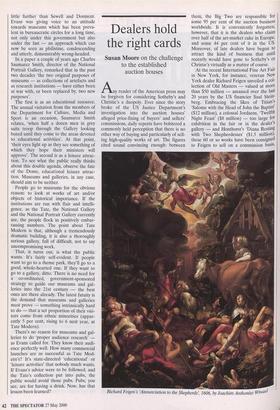

People go to museums for the obvious reason: to look at works of art and/or objects of historical importance. If the institutions are run with flair and intelli- gence, as the Tate, the National Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery currently are, the people flock in positively embar- rassing numbers. The point about Tate Modern is that, although a tremendously dramatic building, it is also a thoroughly serious gallery, full of difficult, not to say uncompromising work.

That, it turns out, is what the public wants. It's fairly self-evident. If people want to go to a theme park, they'll go to a good, whole-hearted one. If they want to go to a gallery, ditto. There is no need for a co-ordinated, government-sponsored strategy to guide our museums and gal- leries into the 21st century — the best ones are there already. The latest fatuity is the demand that museums and galleries must prove — something intrinsically hard to do — that a set proportion of their visi- tors come from ethnic minorities (appar- ently 5 per cent, rising to 6 next year, at Tate Modern).

There's no reason for museums and gal- leries to do 'proper audience research' as Evans called for. They know their audi- ence perfectly well. How many commercial launches are as successful as Tate Mod- ern's? It's state-directed 'educational' or `leisure activities' that nobody much wants. If Evans's advice were to be followed, and the Tate's collection put into pubs, the public would avoid those pubs. Pubs, you see, are for having a drink. Now, has that lesson been learned?

Previous page

Previous page