Dealers hold the right cards

Any reader of the American press may be forgiven for considering Sotheby's and Christie's a duopoly. Ever since the story broke of the US Justice Department's investigation into the auction houses' alleged price-fixing of buyers' and sellers' commissions, daily reports have bolstered a commonly held perception that there is no other way of buying and particularly of sell- ing high-quality works of art. The figures cited sound convincing enough: between them, the Big Two are responsible for some 95 per cent of the auction business worldwide. It is conveniently forgotten, however, that it is the dealers who claim over half of the art-market cake in Europe, and some 44 per cent of it in the US. Moreover, of late dealers have begun to attract the kind of business that until recently would have gone to Sotheby's or Christie's virtually as a matter of course. At the recent International Fine Art Fair in New York, for instance, veteran New York dealer Richard Feigen unveiled a col- lection of Old Masters — valued at more than $50 million — amassed over the last 20 years by the US financier Saul Stein- berg. Embracing the likes of Titian's. `Salome with the Head of John the Baptist' ($12 million), a colossal Jordaens, 'Twelfth Night Feast' ($8 million) — too large for exhibition in the fair or in the dealer's gallery — and Honthorst's 'Diana Resting with Two Shepherdesses' ($1.5 million), these 60 or so works have been consigned to Feigen to sell on a commission basis,

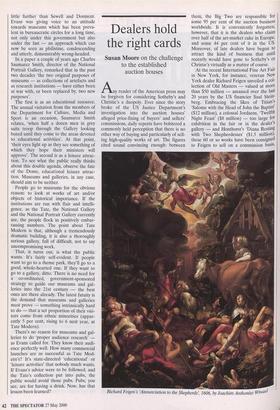

el Richard Feigen's 'Annunciation to the Shepherds, 1606, by Joachim Anthonisz Wiwa rather than go to the block in a smart sin- gle-owner sale.

While the auction houses have estab- lished a reputation for being the best place to sell everything, Feigen is among those who believe that Old Masters almost never do well in the saleroom unless they happen to be decorative. He certainly feels that all three of the pictures Saul Steinberg did con- sign to Sotheby's over the last three years a Rembrandt, Sweerts and a Domenichino — failed to achieve appropriate prices. ' "Difficult" pictures take time to place and to sell,' he says, 'particularly to a museum which cannot quickly mobilise its resources.' Even so, at the fair's benefit vernissage, he sold a $3.2 million Jan Breughel and a $1.2 million Cranach, and various others went on reserve. Cavallino's 'Galatea' has already gone to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, and several other museums have options on particular pictures.

Such a major consignment to a dealer is perhaps unprecedented in living memory but, interestingly, it is now paralleled by the case of another American private col- lector who has sold his outstanding collec- tion of English neo-classical furniture and works of art to London dealers Mallett. This £7.5 million collection, including the largest collection of Matthew Boulton in the world, and which was — revealingly also all acquired privately, goes on show next month. Some collectors understand- ably value the discretion, and the more per- sonal relationships, afforded by a dealer. It would seem that the significant number of senior Sotheby's and Christie's business- getters and experts who have swapped the saleroom for the dealer's gallery in recent years understand that too.

As Richard Feigen presented the Stein- berg pictures at the Armory opening, so, across town, Phillips, the world's third- ranking auction house, made its first strate- gic move on the top end of the art market. On offer in its first major sale since its acquisition in November by the French lux- ury goods group LVMH Louis Vuitton Moet Hennessy, was a multi-million dollar group of Impressionist and Modern mas- ters, all but one of which had been secured by Phillips in competition with its rivals either by outright purchase — such as its star lot, Malevich's 1919 `Suprematist Com- position' — or by offering vendors a range of financing. It was not the most brilliant or successful of debuts, with only desultory bidding and about 60 per cent sold, but it achieved a respectable $17 million for the Malevich and was far from the humiliating debacle that Geneva-based auctioneers Hapsburg, Feldman met when they tried to muscle in on the action in New York back in 1989. Perhaps most crucially, however, by revealing the precise nature of the financial arrangements made for each of its lots, Phillips have clearly indicated a trans- parency of procedure and the message that it plans to play straight.

LVMH's Bernard Arnault has briefed his senior staff to 'make the best auction house in the world — and do it quick'. He has also provided them with an instant sale platform in France through his recent acquisition of Etude Tajan, thus stealing a march on his rivals, and grand or refurbished premises are planned for Paris, New York and Lon- don. Although no one is yet in a position to predict the effect of the Internet on the top end of the market, LVMH, predictably, has a finger in that pie too, with a major stake in iCollector. M. Arnault's rivalry with Christie's owner Francois Pinault should not be under-estimated, nor should the depth of his war chest.

Even discounting the development of the Net, it seems that in the wake of the Sothe- by's/Christie's anti-trust scandal, with the ever-strengthening position of the dealers, the rise of Phillips and the opening up of Paris, the present structure and nature of the international art market is about to fragment.

Previous page

Previous page