Exhibitions 1

Sir Edward Borne-Jones: The Legend of the Briar Rose (Agnew's, 43 Old Bond Street, London Wl, till 17 December)

Awake to the world

John Spurling

'The Legend of the Briar Rose' was first shown at Agnew's in 1890 and Old Bond Street was congested with carriages as 'thousands of the most cultivated people in London hastened to see and passionately to admire, the painter's masterpiece. This was at the zenith of Bume-Jones's career, when he stood for an aesthetic idea, a way of seeing, which made him briefly the cen- tre of fashion. It did not last even the eight years he had still to live and it did his repu- tation such damage posthumously that, during the long reaction against everything High Victorian, he sometimes seemed to be Public Enemy Number One.

Yet there was nothing superficial or pub- licity-seeking about the man himself. Sensi- tive, thoughtful and articulate, sensual and humorous — his comic sketches of himself and his fat friend William Morris, previews of Laurel and Hardy, are as sharp and funny as the anecdotes he told at dinner. tables — he was so genuinely modest as to call himself once 'a fifth-rate Florentine'. He did not like Morris's deep involvement with socialists because he thought they were wasting his friend and hero's energy, but he was anti-imperialist at the height of imperial fervour, anti-nationalist, and a passionate supporter of Gladstone's attack on the Tory government's inaction at the time of the Bulgarian atrocities. He was very much awake to the world, large and small, around him, but at the same time a visionary whose vision never faded. It was no doubt this rare combination that made him as much a craftsman as an artist.

His specialty, the essence of his art, was, like Keats before him or Isak Dinesen after him, to be able to enter and convincingly inhabit a world of myth and fairytale, 'that strange land more true than real', as he called the stories Of King Arthur and the Grail Quest which obsessed him for most of his life. In this he was heir to the Pre- Raphaelites and their mediaevalism, though more consistent, more of a genuine believer than any of them, so that, if he began by following a movement, he soon transformed it into a personal quest, the source of his own creative energy. His instantly recognisable 'style' can seem weary and flaccid in his less successful work — he painted, drew, designed, illustrated too much — but in his best work it comes from within and glows accordingly, the direct visual expression of his powerful romantic imagination.

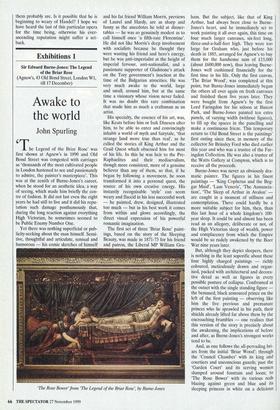

The first set of three 'Briar Rose' paint- ings, based on the story of the Sleeping Beauty, was made in 1871-73 for his friend and patron, the Liberal MP William Gra- 'The Rose Bower' from The Legend of the Briar Rose; by Burne-Jones

ham. But the subject, like that of King Arthur, had always been close to Burne- Jones's heart, and he immediately set to work painting it all over again, this time on four much larger canvases, six-feet long, three-and-a-half-feet high. They were too large for Graham who, just before his death in 1885, arranged for Agnew's to buy them for the handsome sum of £15,000 (about £600,000 now), thus leaving Bume- Jones well cushioned financially for the first time in his life. Only the first canvas, 'The Briar Wood', was completed at this point, but Burne-Jones immediately began the others all over again on fresh canvases and finished them five years later. They were bought from Agnew's by the first Lord Faringdon for his saloon at Buscot Park, and Bume-Jones painted ten extra panels, of varying width (without figures), to fill up the spaces in the panelling and make a continuous frieze. This temporary return to Old Bond Street is the paintings' first outing since then, in memory of the collector Sir Brinsley Ford who died earlier this year and who was a trustee of the Far- ingdon Collection. He was also a trustee of the Watts Gallery at Compton, which is to receive all the proceeds.

Bume-Jones was never an obviously dra- matic painter. The figures in his finest paintings — 'King Cophetus and the Beg- gar Maid', Taus Veneris', 'The Annuncia- tion', 'The Sleep of Arthur in Avalon' — are caught in a moment of stillness and contemplation. There could hardly be a more suitable subject for him, then, than this last hour of a whole kingdom's 100- year sleep. It could be and almost has been read as an allegory, deliberate or not, of the High Victorian sleep of wealth, power and complacency from which the Empire would be so rudely awakened by the Boer War nine years later.

But, although they depict sleepers, there is nothing in the least soporific about these four highly charged paintings — richly coloured, meticulously drawn and organ- ised, packed with architectural and decora- tive detail as well as figures in every possible posture of collapse. Confronted at the outset with the single standing figure — the bemused, black armoured prince on the left of the first painting — observing like him the five previous and premature princes who lie sprawled in his path, their shields already lifted far above them by the encroaching brambles — one realises that this version of the story is precisely about the awakening, the implications of before and after, as Burne-Jones's strongest works tend to be.

And, as one follows the all-pervading bri- ars from the initial 'Briar Wood'; through the 'Council Chamber' with its king and courtiers and unconscious guards; past the 'Garden Court' and its serving women slumped around fountain and loom; to 'The Rose Bower' with its various reds blazing against green and blue and its sleeping princess in white on a delicious pink pillow, one remembers that, of course, it is a love story. Never, surely, was any lover's kiss so brilliantly, so erotically, so wittily delayed among the thorns and inci- dental curiosities — sleeping birds, a strange sundial, an open jewel box — as this one from left to right of some 40 feet of narrative canvas. It would be a mistake to bring your carriage into Old Bond Street this time, but even more of a mistake not to cut your way there somehow through London's tangle.

John Spurling's play King Arthur in Avalon, partly inspired by Burne-Jones's last painting, was recently performed by Cheltenham Ladies' College for the 1999 Cheltenham Festival of Literature.

Previous page

Previous page