DEATH IN THE MORNING

Charles Glass remembers his friend

Dany Chamoun, whose family was butchered last week

THE first time armed men broke into his house in the dead of night, Dany Chamoun was nine years old. It was 11 November 1943. French marines and Senegalese sol- diers came to arrest his father, a popular Maronite lawyer and politician named Camille Chamoun. Other soldiers were arresting the Lebanese President, Bishara El-Khoury, his ministers Saeb Salam and Adel Osseiran and a member of parlia- ment, Abdel Hamid Karami. The French were responding to Lebanon's crime of declaring an end to the French Mandate over Lebanon that had begun in 1920.

'I have a vivid memory of the night they surrounded the house,' Dany Chamoun told me at his ski chalet in Mount Lebanon in 1987. 'I saw a huge Senegalese soldier standing outside both windows. My father couldn't escape. They came at three-thirty in the morning and finally left at eight. They let him dress, and they took him away.'

The French put the elder Chamoun and the other Christian and Muslim politicians into prison in the village of Rashaya. In one of the first and last acts of Christian- Muslim unity in the country's history, Lebanese of all sects rioted, demanding their leaders' freedom and the country's independence from France. Unable to govern the country, and coming under pressure from Britain and the United States to withdraw and concentrate on liberating France from Germany, the French recognised Lebanese independence and released the Lebanese they had arrested.

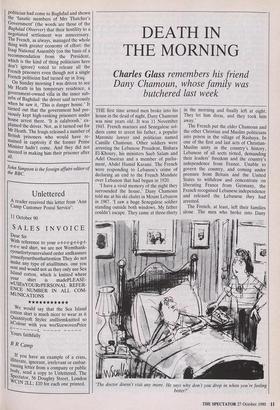

The French, at least, left their families alone. The men who broke into Dany 'The doctor doesn't visit any more. He says why don't you drop in when you're feeling better?' Chamoun's house last Sunday morning observed no such etiquette. When Dany answered the door at about seven o'clock they shot him dead with pistols, the sound muffled with silencers. According to press reports from Beirut, they then shot his German-Lebanese wife, Ingrid. When she was dead, they went into the room where their two young sons were asleep. They shot them as well. The older boy, eight- year-old Tarek, died in bed. His little brother, six-year-old Julien, died of his wounds later that day in hospital. The assassins in camouflage clothes and face masks escaped in two cars, apparently unaware that they neglected to murder Dany Chamoun's 11-month-old daughter, Tamara. She is alive, as is Tracey, Dany's older daughter by his first marriage, who lives in London.

The Syrians have firmly taken hold of Christian east Beirut, whose population has been ravaged over the last year in fighting between rival Christian factions the army units under General Michel Aoun and the Lebanese Forces militia under Samir Geagea. Syria has defeated Aoun, whose forces surrendered and who has taken refuge in the French embassy. Dany Chamoun, a consistent opponent of Syria's presence in Lebanon and architect of the Christian alliance first with Israel and more recently with Iraq, decided to remain at home in east Beirut despite the Syrian victory and the disarming of his body guards. Other anti-Syrian Christian Lebanese had already been liquidated, and reports from Beirut indicate that Syria's own Lebanese Christian Gurkhas, headed by Elie Hobeika — who, when he worked for Israel, conducted the Sabra-Shatila massacre — have a free hand to dispose of Hobeika's and Syria's enemies.

Dany Chamoun was born in Lebanon in 1934, the son of a man who in 1952 would become the country's president. Dany and his older brother, Dory, came to England to study at Loughborough College and went home for holidays to a Lebanon that Dany remembered fondly as Lebanon's belle epoque. 'I remember coming back here,' he said in 1987, 'and there would be a royal visit from Athens, King Paul, Queen Frederika, Prince Constantine and what's-her name, Sophie. Those were very pleasant days, very grand.' In 1957, the older Chamoun, a sportsman and hand- some ladies' man as his son would become, embraced the Eisenhower Doctrine. It permitted American intervention to save Middle Eastern governments from com- munism or any form of nationalism that could be made to look like communism. In 1958, when Muslim militias supported by Egypt's Gamal Abdel Nasser threatened his government, Chamoun called for American help. None was forthcoming until 14 July of that year, when the Iraqi army under General Kassem overthrew the Hashemite monarchy in Baghdad. Fearing the Iraqi revolution would spread, Presi- dent Eisenhower sent the Marines to Beirut to restore order. Until the latest Iraqi adventure in the region, that was the largest deployment of American forces in the Arab world.

If the Iraqi revolution and Iraq's with- drawal from the western Baghdad Pact saved Camille Chamoun, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait led directly to his son's and grandsons' murders. After the American decision to send troops to Saudi Arabia to face the Iraqis, the United States began fishing for allies to send troops or money or both to that shield in the desert. One head of state who was only too willing to undermine the Iraqi leader, Saddam Hus- sein, was his longtime rival in Damascus and fellow Baath Party adherent, Hafez al-Assad. Assad was so anxious to see Saddam overthrown that he berated the French for not sending enough soldiers to Saudi Arabia to support the Americans. All this from the very man who had driven the Americans out of Lebanon in 1984.

Syria willingly despatched a contingent of its own. Secretary of State James Baker visited Damascus, an important gestu're to President Assad. American officials in Washington now say that the United States agreed, in return for Syrian support for opposing an enemy Syria had opposed anyway, to turn an even blinder eye to Syrian actions in Lebanon. In other words, the Syrians could move into east Beirut, crush General Aoun's rebellion and 'unite' Lebanon. The United States would say indeed has said — nothing. The Chamoun family were among many victims of this dumbness.

Syria has triumphed. The Lebanese will not be rioting to make any demands. The Americans and British will not force Syria to do what the French did in 1943: grant Lebanon its independence. The West, particularly the United States, has sacri- ficed Lebanon on the altar of its crusade against Iraq.

No one who covers the Middle East for any length of time can avoid making friends with men who will be assassinated. Sometimes they are Palestinians who die at 'Are you a screw or Gerald Ronson's chauf- the hands of Israeli death squads in south Lebanon or Gaza, Palestinians who die at the hands of Iraq or Syria because of their support for dialogue with Israel, Lebanese who oppose the militias or Syria, or Iraqis who speak out against their government from the supposed safety of exile. Said Hammami was the Palestine Liberation Organisation representative in London. His crime, in the eyes of the assassin Abu Nidal and his paymasters in — was it Syria then or Iraq? — was that he urged Palesti- nians to negotiate their future directly with Israel, not that the Israeli government ever wanted such a course. He was shot dead more than ten years ago in his London office.

Said's colleague, a Palestinian physician in Paris named Issam Sartawi, would come to my house and play with my children. He was the gentlest of men. He met openly with Israeli politicians, like the retired General Matti Peled, who sought peace with the Palestinians. Sartawi condemned the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982 and the Syrian occupation of Lebanon with equal vehemence. He once told me the United Nations should send a force to Syria to depose the regime there and • impose justice. Not surprisingly, Abu Nid- al, who was working from Damascus then, murdered Issam too. That was in Portugal in 1983.

Now Dany Chamoun has joined their ranks, a martyr in the minds of his family's many Maronite followers. He was too open in his dealings with Israel after 1976, with Iraq since 1987, and intermittently with Yasser Arafat, for the Syrians to tolerate him any longer. Other Lebanese did as he did, but they were quiet about it. The last time we met in the mountains where he skied in winter and shot partridges in the autumn, he watched his little boys playing in front of his house. I asked if Lebanon were a good place to raise his sons.

'I don't know. Is New York any better really when you think of the Mafia, of the violence there?'

I pressed the point, and he said, 'I know, but what do you do with the people here? You were born here. This is your country• . . But the fact is this is an important project for me: to try to make a viable and beautiful home for my family, for the rest of the Lebanese. Why should I leave here? I mean, consider these people who live here. You know that every single house probably has a machine gun or two. Now look at them. There isn't a policeman for 25 or 30 kilometres. And even if there were, he'd probably be drinking coffee or smoking a cigarette. Yet look at the rate of crime here. There isn't any. I'd like to see any port of the world which has this, even Switzerland — Switzerland is the most police-run state you can find. Nobody has what we have here.' That really was true in the Christian zone of Lebanon until 1988, when the Christians turned on one another.

Previous page

Previous page