Now is the time for all good men to come

to the aid of the-party. How well I know that moment—it means that the host's best friend is face down in the beef sandwiches again, that the host's wife's school chum who rarely gets invited out is making a pig of herself insulting

the only distinguished guest, that a gate-crasher has fallen asleep across the children, that there is an apoplectic man in pyjamas and a dressing-gown ringing the down- stairs bell, that there is nothing left on the side- board but cider and Drambuie, that some traitor is secretly recruiting a group to defect to another party where orgies have been advertised for mid- night—let the good men rally round, I'm afraid 1 have to get back for the baby-sitter. Don't think it hasn't been fun because it hasn't. Some- how the best parties are always those you haven't been invited to, only bettered by those you were invited to but didn't attend.

These are the ones which become legends— the kind I go to remain myths. Sometimes; when pressed for an anecdote, I have pretended that I was there the time the theatrical dame did a strip- tease, when the press lord showed the obscene film taken by the Tory MP of his honeymoon, when the tough-guy novelist had his chest shaved with a lady's electric razor, when the book critic threw the novelist out of the window in an arm- chair, when they added meths to the grand old don's drink and then lit his breath, when the man- in-the-mask served the dinner naked. But I never was. Despite a lot of ruthless cross-examining, I have rarely discovered anybody else who will back up his story with names and dates and places.

There is a crabbed, cynical, stay-at-home school of thought which argues that such parties never have occurred. It traces them back to that secret and bottomless repository of folk-jokes, that quarry of unprintable tittle-tattle, where layer upon layer of fossilised fantasy about Christine Keeler, the Duchess of Argyll, President Ken- nedy, Diana Dors, Errol Flynn, Charles Chaplin, Brendan Bracken, Lord Beaverbrook, Hitler, Gandhi, and the Royal Family lies awaiting ex- h_imation by the social geologist. I expelled my- self from that school some years ago when I was touched by the revelation-1f you can imagine it, somebody has done it.' However anatomically improbable, however psycho- logically incredible, the details appear to you, never undersell a story just because it seems too good, or too bad, to be true. a good party should be that any undressing is calculated and partial. Its war dances are formal and ceremonial. Its mating rituals follow care- fully rehearsed patterns of come-hither and get- thence. Insults can be swapped and compliments exhibited without honour insisting on a fight or dishonour on a fumble. A party ought to re- semble an elaborate game for civilised grown- ups—an emotional outing into Cloud-Cuckold- Land conducted according to the rules of courtly love, an intellectual bout of opinionated jousting during which an opponent is unseated but never impaled. Flirting, boasting, arguing, intriguing, feuding, confessing, dancing, drinking are all legitimate forms of self-expression. They should be dangerous without being fatal, serious without being boring, amusing without being hysterical, competitive without being pugnacious. No one of any couple ought afterwards to recall what was said unless both agree to remember. The parties which remain in your memory over the years are not those you can dine out on—they are those where all the guests seem founder-members of a club convened to last for one night only. You should feel that you would like to have more friends, not that you have too many acquain- tances.

Pleasure is always precarious. It is hard to imagine the party spirit distilled without alcohol —even that most innocently convivial band of roisterers, the Pickwick Club, turns out to have been continually boozed to the side-whiskers when you count the bottles in the text. But drink means drunks. Oddly enough one drunk at a party is more ruinous than a dozen. He breaks the illusion, and upsets the balance, like the spec- tator who runs on to the field or the passenger who climbs out of the roller-coaster. He eddies round the room like a sodden parcel of old rubbish, threatening to burst his seams with abuse, vomit or lechery at every damp contact.

Hosts are rarely drunk—the nervous tension of playing Father to so many friends seems to burn off the alcohol like a five-mile run. If they have a fault as a breed, it is that even the most perfectionist of them knows too many bores and button-holers. So long as you avoid these until late enough in the party, they are usually pain- less—like having a tooth extracted under novo- caine. Bores execute some surprisingly nifty foot- work until they have you boxed between the door and the window, then they fire off at an angle over one of your shoulders. The button-holers move from side to side following your eyes, like a seal waiting to be fed, and once they have you nose to nose begin a close bombardment between the eyebrows. To the bore, at least silence means consent. To the button-holer, any answer sig- nifies dissent and provokes heavier barrages.

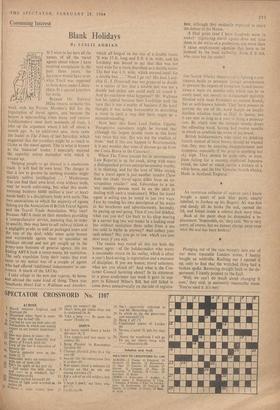

Chess

By PHILIDOR No. 167. H. VAN BEEK (Second Prize, Haagshe Post, 1921) BLACK (8 men) WHITE (II men)

WHITE to play and mate in two moves; solution next week. Solution to No. 166 (Bernard): R-Q 1, no threat. 1 . . . Q moves; 2 R-KB I or Q x KBP (set Kt-Q 3 or Kt-K 6). 1 . . . Kt-B 3 or P-Kt 3; 2 Q x P (set Kt-K 6). 1 . . . Kt-B 5 or P-Kt 4; 2 R-KB I (set Kt-Q 3). 1 . . . P-B 4; 2 Q-K 5 (set P-K 5). 1 . Px R=Q or P-B 8=Q; 2 Q-KR 2.

. P-K 7; 2 Q-B I. Attractive focal mutate.

What are Problems About?

What they are not about is winning—they are concerned not with chess as a struggle, but with chess as an art. The criticisms one so often hears that the positions are unnatural or silly arise from a failure to appreciate this basic point. The best way to put some flesh on the bare bones of this statement is to look at last week's problem and its solution; for the benefit of those foolish virgins who have not kept the position as recommended, it was: White, K on QR 8; Q on QKt 2, R on Q 4, Bs on KR 4, KR 5, Kts on QB 5, Q 7, Ps on Q 5, K 4. Black, K on KB 5, Q on QR 3, Kt on QR 4, Ps on QR 2, QKt 2, QKt 6, QB 7, K 6, KB 3. The first thing for the non-problemist to observe is that the position is preposterous in relation t the game: the king positions are ridiculous and White has an extra rook, two bishops and knight, and can win the queen at once by Kt-K 6 ch or Kt-Q 3 ch. So this is not an imitation game position'; Next, if we look carefully we see that if Blac were to move first, then whatever he moved woul allow White to mate at once—e.g., 1 . . . Q moves 2 Kt-K 6 or Kt-Q 3 mate or 1 . . . P-B 4; 2 P-K mate and so on. Such mates are called 'set' mat being mates that exist in the position as originally s r z. a 4. %A/ 4:).

A A /

4/4 4 A r/ A

A

/ r

/ /

A , : IA- ' 4 •,;/A •

a , A ,

Previous page

Previous page