A forecast for the Horn

Anthony Mockler

Where will the Ethiopians strike? Heavy Soviet tanks, rocketry and other equipment has been pouring in, powerful forces are now massing at Diredawa, considerable numbers of Cubans, South Yemenis and indeed Russians (not all in the role of advisers) are on the spot.

There can no longer be any serious doubt that the counter-attack is due — and due soon before the 'little rains' at the end of February turn the whole tip of the Horn into a quagmire.

In this article I will try to explain what might happen, militarily, within the next few weeks. But first a proviso: as I stressed in my last article on this war (issue of 3 December 1977) the fact that no reporters on either side have been allowed up to the front means that the basis on which the whole world (now at last interested) is being informed of what is happening is very thin. Had or had not Harar fallen, I then asked? It now seems it had not; and yet even at the beginning of this week there were reports — third-hand, as usual — of street fighting in the city. This may be the final drive by the Ethiopians to winkle out the guerrillas who have been infiltrated over the past weeks. Or, on the other hand, the Somalis may yet pull off an unexpected coup.

But if they do pull off a victory, it will be unexpected not only by the world but by the

Somalis themselves. Ethiopian declarations of a looming counter-attack are balanced by more and more frantic appeals from the Somalis to the West for help. Whether the Somalis ought or ought not to be aided is morally debatable; but this article is no more concerned with morality than was Machiavelli. I do not believe they will get help — or at least not in time.

Once the Ethiopian counterattack is successfully launched and the tanks are rolling down from the mountains, there is nothing to stop them sweeping as swiftly over the low-lying deserts of the Ogaden in one direction as the Somalis have already done in the other. There are no natural boundaries or lines to be held; in military terms the whole expanse is one vast field for manoeuvre. Indeed, once the initial battle has been fought and the chase is on, there is really no reason why within ten days Ethiopian tanks should not be a thousand miles to the south-west, in the streets of Mogadishu.

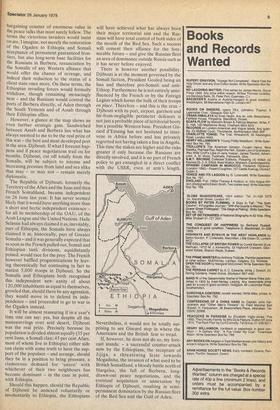

Of course the Americans may move, or the Shah of Iran may send in an expeditionary force, and the whole balance may change once again. But assuming this does not happen, my precise forecast is this:a large armoured force will move north from Diredawa, swing round the mountains, and come down through the desert (possibly using the frontier road inside Somalia) to recapture Jijiga — and probably detaching en route a column to secure the Jirre Pass on the road to Zeila. At the same time there will be a frontal attack up from Diredawa through Harar against the Somali position at the Babile Gap. After a bloody and ferocious tank battle, Jijiga will fall; the Somali troops (15,000?) up in the moun tains will be cut off and will either fight on and, attacked from front and rear, be annihilated, or melt away, abandoning their heavy equipment, into the hills to the south.

The Ethiopians will then have re-es tablished themselves at what has always been the base from which they have domi nated the Ogaden — Jijiga. They will have avenged their defeat, saved Harar, regained the initiative — and be able to choose their next objective at will, a splendid strategical position to be in.

Theoretically they should strike back into the Ogaden, take the road to Daggabur, and simply recapture all that had been lost last summer, halting at the frontiers and sagely ending the war. In fact, of course, a column of excitable tanks does not come up against an invisible line on the sand-dunes and then stop. Jijiga — Daggabur — the frontier — and then less than 200 miles on to Mogadishu; occupy the enemy capital, overthrow the regime, destroy the Somali armed forces and thus remove the Somali threat for ever, — that is certainly a temptation and something which, in my view, the Ethiopians, heady with victory and revenge, will be longing to attempt.

But reports are that the Ethiopian War Cabinet now consists of five Russians, nine Cubans, two South Yemenis, and only six Ethiopians. In other words, the majority of those directing the war are not interested in the ancient rivalry between the Ethiopians and the Somalis and would be chary about destroying what is a sovereign and was once a client state.

There is no reason to suppose that, Jijiga once recaptured, a column will not head down towards Daggabur. But I would expect the main thrust of the Ethiopian counter-attack to go North — to take the easy road to Hargeisa and then launch through the four passes (just as the Italians did in 1940 when they successfully invaded what was then British Somaliland) a fourpronged attack towards Zeila and Berbera. The fiercest battles will be — as they were

then — at Tug Argan, on the main Hargeisa-Berbera road, with a supporting

thrust to the east at the Pass of El Sheikh. And after ding-dong fighting for two or three days, the invaders in overwhelming force, will break through — and Berbera will fall.

What will this have achieved? First of all, the Russians will be rubbing their hands with delight, for they will have recovered the elaborate missile sites and base facilities that they had built up in Berbera before they were booted out so abruptly by the ungrateful Somalis.

But, far more important than that, the territory invaded and controlled will be a

bargaining counter of enormous value in the peace talks that must surely follow. The terms the victorious invaders would insist on are, I imagine, not merely the restoration of the Ogaden to Ethiopia and Somali acceptance of permanent guaranteed frontiers, but also long-term base facilities for the Russians in Berbera, renunciation by the Somalis of any Western alliance that would offer the chance of revenge, and indeed their reduction to the status of a client state once more. On these terms, the Ethiopian invading forces would formally withdraw, though remaining menacingly near — and the Russians would control the ports of Berbera directly, of Aden through the South Yemenis and of Assab through their Ethiopian allies.

However, a glance at the map shows an even further strategic gain. Sandwiched between Assab and Berbera lies what has always seemed to me to be the real prize of this war — the best and most developed port in the area. Djibouti. If what! forecast happens and if peace negotiations trail on for months, Djibouti, cut off totally from the Somalis, will be subject to intense and increasing pressure from land and sea alike that may — or may not — remain merely diplomatic.

The Republic of Djibouti, formerly the Territory of the Afars and the Issas and then French Somaliland, became independent on 26 June last year. It has never seemed likely that it would have anything more than a short and hectic independent existence — for all its membership of the OAU, of the Arab League and the United Nations. Haile Selassie had always claimed it as, inevitably, part of Ethiopia, the Somalis have always claimed it as, historically, part of Greater Somalia — and it was generally expected that as soon as the French pulled out, Somali and Ethiopian tank divisions, equidistantly poised, would race for the prey, The French however baffled prognostications by leaving theoretically but continuing in fact to station 5,000 troops in Djibouti. So the Somalis and Ethiopians both recognised this independent new entity of about 120,000 inhabitants as equal to themselves, growled that, should there be any agression, they would move in to defend its independence — and proceeded to go to war in the Ogaden instead.

It will be almost reassuring if in a year's time one can say: yes, but despite all the manoeuvrings over arid desert, Djibouti was the real prize. Precisely because its population is divided almost equally (55 per cent Issas, a Somali clan; 45 per cent Afars, most of whom live in Ethiopia) either side can claim with some truth to have the support of the populace — and arrange, should they be in a position to bring pressure, a clamorous demand for `union' with whichever of their two neighbours has become dominant — in the case in point, with Ethiopia.

Should this happen, should the Republic of Djibouti be annexed voluntarily or involuntarily to Ethiopia, the Ethiopians will have achieved what has always been their major territorial aim and the Russians will have total control of both sides of the mouth of the Red Sea. Such a success will cement their alliance for the foreseeable future — and give the Russian fleet an area of dominance outside Russia such as it has never before enjoyed.

There is however another possibility. Djibouti is at the moment governed by the Somali faction, President Gouled being an Issa and therefore pro-Somali and antiEthiop. Furthermore he is not entirely uninfluenced by the French or by the Foreign Legion which forms the bulk of their troops en place. Therefore — and this is the crux — Djibouti with its port, airport, garrison and far-from-negligible perimeter defences is not just a probable piece of territorial booty but a possible Western base. President Giscard d'Estaing has not hesitated to intervene in AfriCa before and has privately regretted not having taken a line in Angola. This time the stakes are higher and the risks greater if only because the Russians are directly involved, and it is no part of French policy to get entangled in a direct conflict with the USSR, even at arm's length.

Nevertheless, it would not be totally surprising to see Giscard step in where the Americans and the British fear to tread.

If, however, he does not do so, my forecast stands: — a successful counter-attack now by the Ethiopians, the recapture of Jijiga, a threatening feint towards Mogadishu, the invasion of what used to be British Somaliland, a bloody battle north of Hargeisa, the fall of Berbera, longdrawn-out peace negotiations, and the eventual acquisition or annexation by Ethiopia of Djibouti, resulting in semi-permanent domination by the Russian fleet of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

Previous page

Previous page