THE ARCHITECTURE OF ZIONISM

Gavin Stamp looks for a

style of building suited to the Israeli state

MOUNT Scopus lies to the north-east of the old city of Jerusalem. The name comes from the Greek, to observe, and from this hill the prospect is magnificent. In one direction are the walls, domes and towers of Jerusalem; in the other, the ground descends towards the Jordan valley and all is white and brown, without a trace of green. For Jerusalem lies on the watershed between the Mediterranean and the Jordan valley and all beyond seems barren and hostile, notwithstanding the Jewish settle- ments which have been planted there as politically provocative dormitory suburbs. It was from Mount Scopus that both the Romans and the crusaders launched their assault across the intervening valley to take the walled city. And here lie the British soldiers who died in the campaign to push the Turks out of Palestine and liberate Jerusalem (the Germans are buried at Nazareth). The British war cemetery was designed by Sir John Burnet, principal 'It's terribly exciting — we've found a refugee hole at the vicarage.' architect to the Imperial War Graves Com- mission for Gallipoli and Palestine, and it is one of the most impressive works by that great beaux-arts-trained Glaswegian. Be- hind the rows of graves that face towards the ancient city (and today, alas, towards the vulgar intrusion of the Hyatt Regency Hotel) is the memorial chapel, a powerful, blocky mass with a strong hint of the mausoleum of Theodoric at Ravenna. Either side of this are curving walls, terminated by pylons, on which are carved the names of the missing — 3,382 soldiers, mostly Australian, whose bodies were nev- er found after Allenby's campaign.

Names, endless names. Jerusalem seems full of names, of the living as well as the dead. Right next to the British war cemet- ery is the Hadassah University Medical Centre. Here, in the entrance hall, a wall is covered with the names of those who paid for the hospital's 'rebirth' after the interval of 1948-67 when, Mount Scopus being an enclave within Jordanian territory, it could not be used. The original building was the largest work in Palestine by the disting- uished German refugee from Nazism, Eric Mendelsohn. Opened in 1938, it sits on the top of Mount Scopus like a huge ship: long, low rectilinear blocks run to the brow of the hill and point towards the Jordan. It is austere, Modern, uncompromising, and beautiful.

Beyond the hospital is the Hebrew University, with which it is associated. At the far end of this is an open amphitheatre in which Lord Balfour — he of the Dec- laration — inaugurated the Zionist institu- tion in 1925. In the centre of the campus is what used to be the National Library, a rugged building of rubble stone with a low dome and strong oriental overtones, de- signed by Benjamin Chaikin and Sir Frank Mears, the son-in-law of Patrick Geddes, the Scottish sociologist and planner. Ged- des came to Palestine in 1919 with Chaim Weizmann and energetically promoted the idea of a Zionist university on Mount Scopus, to be dominated by a great domed building. But Geddes and Mears were unacceptable as they were not Jewish, hence the involvement of Chaikin with the library, the only part of the original plan to be realised.

Unfortunately, this interesting experi- ment in a Zionist style is now overwhelmed by the university which has sprouted on Mount Scopus since 1967. Repetitive poly- gons of concrete and glass, faced in smooth stone, designed by David Reznik, now cover the site and create a bland and rather claustrophobic modern campus. And every building bears a name: the name of a donor. Repetitive inscriptions of the type, 'The Ben and Rachel Zizzbaum Family Building', make the whole institution a concrete expression of the dependence of the Jewish state on the American dollitr, and utter bathos is reached with the 'Frank Sinatra International Students' Centre' in the 'Nancy Reagan Plaza'.

All these 20th-century buildings on Mount Scopus neatly illustrate very diffe- rent solutions to the challenge of building in Palestine: whether to be traditional or modern, organic or mechanistic, Western or Eastern. Above all, they highlight a problem which has yet to be resolved: what should be the architecture of Zionism, of Israel, if it is to he modern and distinct from anything Arab or Turkish or British?

These were not matters that much con- cerned the first Jewish immigrants, whose settlements were traditional, inward- looking, stone-built communities like Me'a She'arim, now the suburb of Jerusalem notorious for its fundamentalist Hassidic inhabitants who decline to recognise the state of Israel. Serious interest in an appropriate architecture for Palestine only really emerged after the establishment of the British Mandate.

Perhaps inspired by the example of Lutyens in New Delhi, Austen St Barbe Harrison, chairman of the public works department of the Mandate, fused oriental elements into powerfully massed, essen- tially classical compositions, as at the High Commissioner's residence in Jerusalem. His municipality and post office in the same city have a moderne, streamlined quality typical of the 1930s but his finest achievement is the archaeological museum just north of the walls of the old city. In the centre of this noble, sophisticated building is an open courtyard surrounded by pointed open arcades and filled with a reflecting pool. Here Greek, Roman, Arab and Jewish antiquities sit in calm dignity below a rugged, Byzantinesque tower.

In comparison with these British build- ings, the eclecticism of the YMCA seems naïve. In this prominent Jerusalem land- mark the American, A. L. Harmon, later one of the architects of the Empire State Building in New York, combined Byzan- tine elements and every possible form of religious and cultural symbolism and finished off with a colossal domed tower. The resulting complex of buildings would seem more at home in a Mid-Western campus, but it is more successful than the King David Hotel over the road. Here are decorative schemes of the 1930s in the Hollywood film director's idea of the Hit- tite, Phoenician and Syrian styles.

Rather more interesting are the new Jewish suburbs of Jerusalem laid out after the Balfour Declaration. These were plan- ned, on English garden suburb lines, by the German-Jewish architect, Richard Kauff- mann, the father of Israeli architecture. C. R. Ashbee was impressed:

By far the best constructive planning here is that of the Jews, because the brains and scholarship behind it arc Gcrman'and Au- strian . . . I have the overhauling of Kauff- mann's drawings. Very good they are too . . . . But indeed there's no knowing to what altitudes we may not fly over the Lord's Holy Hill. Kauffmann brought me one day his plans for the Garden Suburb of Talpioth on the Bethlehem side of Jerusalem. I checked off the roads, alignments, houses to the acre, etc, and found all as it should he, when I suddenly came across the blocking out of an interesting plan — a hypothetical building on the crest of the hill. 'And this?' 'Das in unser Parliarnentsgebaude: He and his friends had meant it suite seriously . . .

But that particular Zionist vision took another 40 years to realise, and on a different Jerusalem hill.

But if Kauffmann's planning was partly English in inspiration, his architecture certainly was not, for, by the end of the 1920s, he and other German-trained architects had found the ideal style for Zionism. This was a style perfect for a progressive, Utopian, socialist state; a style

suitable for a Mediterranean climate; a style without traditional overtones, whether British, or Arab, or oriental; a style that was truly international and im- peccably modern — that of the Modern Movement. The architecture of concrete, of flat roofs and pilotis, of sun, air, glass and progress, seemed perfect for an arid, hot landscape — as it also did in South Africa.

Tel Aviv is the most completely realised Modern Movement vision of the 1930s and remains the ultimate test for the continuing worshippers at the shrine of early Func- tionalism. For individual buildings that seem exciting, because different, when found in Hampstead or Frinton seem to lose their charm when surrounded by hundreds of similar neighbours. More de- pressing is the fact that what was once known as the 'White City' is now rather grey, as the smooth concrete is now blotch- ed and stained and the sea air is wreaking havoc with the steel reinforcements.

Not all modern architects fell into this internationalist trap; Mendelsohn, in par- ticular, saw the need for a more thoughtful answer to local conditions than just copying pioneering essays in Modernism like his own. Mendelsohn's Palestinian work is of a high order and his buildings in Jerusalem are among the finest Modern Movement works anywhere. Not only did he design the hospital on Mount Scopus which dares even to sport oriental domes over its entrance colonnade — but also a small skyscraper for the Anglo-Palestinian Bank and a house and a library for Salman Schocken, for whom he had once built department stores in Weimar Germany. Today, all these smooth rectilinear struc- tures look as good as they did when new partly because of Mendelsohn's sound detailing, partly because of Jerusalem's benign climate and unpolluted atmos- phere, and partly because of Sir Ronald Storrs, the British Governor of Jerusalem. who in 1918 imposed the admirable regula- tion that all new buildings in the Holy City

'Well. I think we're stuck in a rut.'

should be of stone. As a result, all Mendel- sohn's concrete forms are clad in clean local ashlar and look all the better for it.

Mendelsohn, the East Prussian-born re- fugee from Nazism, was the most cele- brated architect who worked in Palestine.

Not only was he a great artist who was not limited by the dogmas of Functionalism

and who therefore might have humanised the arrogance of the ascendant Modern Movement, he also had believed that Jew and Arab must work together. In 1940 he wrote:

The unstable urban civilisation based on the one-sided overvaluation of the intellect fails to appreciate the organic culture of the East rooted in the unity of man and nature. But it is this culture which produced the Moral Law and the Visions of the Bible . . . Palestine of today is symbolising the union between the most modern civilisation ai,c1 the most antique culture. In this arrangement, com- manded by this union, both Arabs and Jews, both members of the Semitic family, should be equally interested.

In the event, the architecture of inde- pendent Israel only embraced the mecha- nistic vision. Tel Aviv, Haifa and, to a

lesser extent, West Jerusalem were made into modern cities like anywhere else. Perhaps the most extreme manifestation of this tendency is the University of Haifa on the top of Mount Carmel: a 30 storey tower block of black glass rising from a huge concrete podium. It was designed by Oscar Niemeyer, the architect of Brasilia, who deigned to visit the site of his essay in and geometry just twice.

Naturally, in Israel — as elsewhere — a reaction against this sort of architecture has occurred in the last two decades. Housing is now low-rise and even large new buildings are now broken up into less rigid compositions of repetitive units. But Israeli architects still seem ideologically committed to the Modern Movement as the style for the nation. Even in the

reconstruction of the Jewish Quarter of old Jerusalem, where the old street pattern has

been respected and picturesqueness achieved through changes in level, the vocabulary is a sort of castle-like Brutal- This stylistic problem is particularly evi- dent in the memorial architecture with which Israel is filled: memorials to the wars of 1948 and 1967, memorials to the victims of persecution and genocide. Of these, the Most important is the Yad Vashem Memo- rial to the south-west of Jerusalem. A group of buildings beautifully sited on the spur of a hill, it both documents and is a monument to the unspeakable suffering of the Jews in the Holocaust. A necessary reminder of human wickedness, Yad Vashem also explains and attempts to Justify the creation of Israel by its insist- ence on the exclusiveness of Jewish suffer- ing. Perhaps it is inevitable, therefore, that it is curiously uncertain as an architectural statement.

For Burnet, when designing the British

war cemetery and memorial on Mount Scopus, the classical language was avail- able with all its cultural resonances and monumental significance. But for Israeli architects, no such implicitly expressive language was acceptable for the terrible purpose of remembering six million mur- ders, so the monumentalism of beton brut concrete is combined with the atavistic forms of the Holy City — great pieces of stone. Most powerful is the Okel Jiksor or Tent of Remembrance. A massive roof of raw, shuttered concrete floats just above walls made of huge boulders of basalt. Inside, a flame burns to illuminate letters of bronze placed on the smooth sunken The White Square, Tel Aviv: `moving in its strange beauty' floor: terrible names written in both Heb- rew and Roman letters: Buchenwald, Treblinka, Theresienstadt • .

For the latest addition at Yad Vashem, a memorial to the children who perished in the Holocaust, very different means are employed to create an emotional effect, for it draws upon not so much architectural forms as the vital tradition of the Jewish theatre. Outside it is a sort of rubble stone bunker, marked by banks of broken stone shafts and, distressingly, by prominent glass panels bearing names in the personal- ised American style, informing us that the whole thing was paid for by 'Abraham and Edita Spiegel of Beverley Hills, California, in memory of their son Uziel, killed in Auschwitz, 1944'. Beyond that poignant advertisement, the visitor descends, past photographs of murdered children, to en- ter what seems to be pitch darkness. But here is not darkness but light, for cleverly contrived mirrors repeat the reflections of a candle flame over and over, all around and above and below. The impression achieved is of floating in space, surrounded by all the stars in the firmament — each representing one of the one and a half million innocent lives snuffed out by the Nazis.

In other memorials, more ancient and appropriate traditions are drawn upon. Also in Jerusalem is Yad La-Banim, the Memorial for Fallen Soldiers, which is a composition of stone pyramids. As the architect, David Reznik, argues, 'the pyra- mid has always symbolised the soul ascend- ing to heaven' in ancient memorial monu- ments such as the Tomb of Zechariah and Jason's Tomb. Here, one pyramid has been sliced in half to allow access to a hall with an eternal flame.

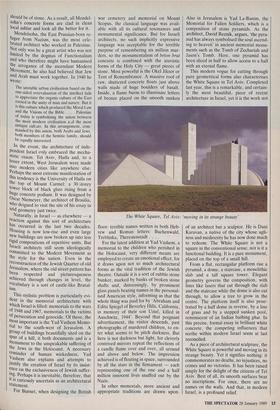

This modern vogue for cutting through pure geometrical forms also characterises the White Square in Tel Aviv. Completed last year, this is a remarkable, and certain- ly the most beautiful, piece of recent architecture in Israel, yet it is the work not of an architect but a sculptor. He is Dani Karavan, a native of the city whose ugli- ness and mediocrity he has now done much to redeem. The White Square is not a square in the conventional sense, nor is it a functional building. It is a pure monument, placed on the top of a small hill.

From a flat, rectangular platform rise a pyramid, a dome, a staircase, a monolithic slab and a tall square tower. Elegant geometry governs the composition, with lines like lasers that cut through the slab and the staircase while the dome is also cut through, to allow a tree to grow in the centre. The platform itself is also pene- trated by a half dome in reverse, by a line of grass and by a stepped sunken pool, reminiscent of an Indian bathing ghat. In this precise, formal essay in brilliant white concrete, the competing influences that seethe within modern Israel seem at last reconciled.

As a piece of architectural sculpture, the White Square is powerful and moving in its strange beauty. Yet it signifies nothing: it commemorates no deaths, no injustices, no crimes and no victories. It has been raised simply for the delight of the citizens of Tel Aviv. Best of all, its smooth surfaces bear no inscriptions. For once, there are no names on the walls. And that, in modern Israel, is a profound relief.

Previous page

Previous page