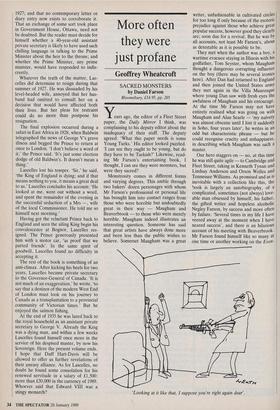

Prince Charming turns into a toad

Kenneth Rose

IN ROYAL SERVICE: THE LETTERS AND JOURNALS OF SIR ALAN LASCELLES, VOLUME II, 1920-1936 edited by Duff Hart-Davis

Hamish Hamilton, £14.95, pp.212 Ng.

Awork on a life of George V, I once asked Sir Alan Lascelles what he could tell Me about the old King. 'I was in the same

room only once', Lascelles replied, 'when he gave me an MVO fourth-class as private secretary to his eldest son. It was the hardest-earned medal I ever had.' From a man who had come through the carriage of the Western Front with a Military Cross, that was a remarkable admission.

Lascelles served the Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII and ultimately Duke of Windsor, from November 1920 to February 1929. He began by thinking him 'the most attractive man I've ever met.' He parted from him in despair, telling the Prince to his face, 'with an accuracy that might have surprised me at the time, that he would lose the throne of England.' And although Lascelles went on to become principal private secretary to both King George VI and to the present Queen, he never forgot or forgave those eight corro- sive years.

That is the theme of In Royal Service, the second volume of the letters and journals of Lascelles, embracing the period 1920 to 1936. Almost everything that has emerged about the Duke of Windsor since his death in 1972 is to his discredit. There has been a wealth of evidence, for inst- ance, about his tenderness for Nazi Ger- many, epitomised by this entry from Robert Bruce Lockhart's diary for 1933:

The Prince of Wales was quite pro-Hitler, said it was no business of ours to interfere in Germany's internal affairs either re Jews or re anything else, and added that dictators were very popular these days and that we might want one in England before long.

It was through no exertion of the Duke of Windsor that Hitler failed to enter London in triumph seven years later. Craven and defeatist, as the German armies massed for a cross-Channel inva- sion of England in the summer of 1940, he sent a message to the Nazi Government from Spain begging for a guard to be put on his house in occupied Paris.

Now the clouds are gathering even over his years as the golden-haired Prince who charmed an Empire. For it was not only Lascelles who could stomach no more of his capricious master. Two other, more senior members of the Prince's entourage, Sir Godfrey Thomas and Admiral Sir Lionel Halsey, confided to Lascelles that they too had long been considering res- ignation. In the end it was he alone who went.

The cause of their rift was not only the Prince's growing impatience with court protocol and punctuality. More serious differences emerge from the account by Lascelles of a private talk with the Prime Minister, Stanley Baldwin, who happened to be in Ottawa during the Prince's Cana- dian tour of 1927:

I told him directly that, in my considered opinion, the Heir Apparent, in his unbridled pursuit of wine and women, and whatever selfish whim occupied him at the moment, was rapidly going to the devil, and unless he mended his ways, would soon become no fit wearer of the British Crown.

I went on, 'You know, sometimes when I sit in York House waiting to get the result of some point-to-point in which he is riding, I can't help thinking that the best thing that could happen to him, and to the country, would be for him to break his neck.

`God forgive me,' said Stanley Baldwin, 'I have often thought the same.'

Duff Hart-Davis, the editor of the Las- celles papers, scrupulously observes that this record was made some years later than 1927; and that no contemporary letter or diary entry now exists to corroborate it.

That an exchange of some sort took place in Government House, Ottawa, need not be doubted. But the reader must decide for himself whether a 40-year-old assistant private secretary is likely to have used such chilling language in talking to the Prime Minister about the heir to the throne; and whether the Prime Minister, any prime minister, would have responded so indis- creetly.

Whatever the truth of the matter, Las- celles did determine to resign during that summer of 1927. He was dissuaded by his level-headed wife, annoyed that her hus- band had omitted to consult her on a decision that would have affected both their lives. But her pleas for restraint could do no more than postpone his resignation.

The final explosion occurred during a safari in East Africa in 1928, when Baldwin telegraphed the news of George V's grave illness and begged the Prince to return at once to London. 'I don't believe a word of it,' the Prince said. 'It's just some election dodge of old Baldwin's. It doesn't mean a thing.'

Lascelles lost his temper. 'Sir,' he said, `the King of England is dying; and if that means nothing to you, it means a great deal to us.' Lascelles concludes his account: 'He looked at me, went out without a word, and spent the remainder of the evening in the successful seduction of a Mrs —, wife of the local Commissioner. He told me so himself next morning.'

Having got the reluctant Prince back to England and seen the ailing King begin his convalescence at Bognor, Lascelles res- igned. The Prince generously presented him with a motor car, 'as proof that we parted friends'. In the same spirit of goodwill, Lascelles found no difficulty in accepting it.

The rest of the book is something of an anti-climax. After kicking his heels for two years, Lascelles became private secretary to the Governor-General of Canada. 'It is not much of an exaggeration,' he wrote, `to say that a denizen of the modern West End of London must look on his journey to Canada as a transplantation to a provincial community of Victorian times.' But he enjoyed the salmon fishing.

At the end of 1935 he was lured back to the royal household as an assistant private secretary to George V. Already the King was a dying man, and within a few weeks Lascelles found himself once more in the service of his despised master, by now his Sovereign. Here the present volume ends. I hope that Duff Hart-Davis will be allowed to offer us further revelations of their uneasy alliance. As for Lascelles, no doubt he found some consolation for his renewed servitude in a salary of £1,500: more than £30,000 in the currency of 1989. Whoever said that Edward VIII was a stingy monarch?

Previous page

Previous page