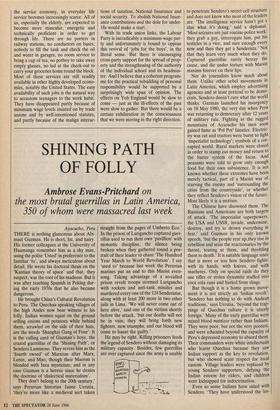

SHINING PATH OF FOLLY

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard on the most brutal guerrillas in Latin America, 350 of whom were massacred last week

Ayacucho, Peru THERE is nothing glamorous about Abi- mael Guzman. He is short, fat, and hairy. His former colleagues at the University of 1-luamanga remember him as a shy man, using the polite 'Listed' in preference to the familiar `tu', and always meticulous about detail. He wrote his doctoral thesis on the `Kantian theory of space' and that, they suspect, was the root of his madness. But it was after teaching Spanish in Peking dur- ing the early 1970s that he also became dangerous.

He brought China's Cultural Revolution to Peru. The Quechua speaking villages of the high Andes now bear witness to his folly. Indian women squat on the ground selling onions and potatoes while behind them, scrawled on the side of their huts, are the words 'Shanghai Gang of Four'. It is the calling card of Guzman's boys, the crazed guerrillas of the 'Shining Path', or Sendero Luminoso. They revere him as the `fourth sword' of Marxism after Marx, Lenin, and Mao, though their Maoism is blended with Inca mysticism; and in any case Guzman is a heretic since he denies the doctrine of `dialectical materialism'.

They don't belong to the 20th century,' says Peruvian historian Jaime Urrutia, `they're more like a medieval sect taken straight from the pages of Umberto Eco.' In the prison of Lurigancho captured guer- rillas used to run their own `pavillion' with monastic discipline, the silence being broken when they gathered round a por- trait of their leader to chant 'The Hundred Year March to World Revolution'. I say `used to' because last week the Peruvian marines put an end to this Maoist even- song. Taking advantage of a so-called prison revolt troops stormed Lurigancho with rockets and anti-tank missiles and murdered every one of the 124 Sencieristas, along with at least 200 more in two other jails in Lima. 'We will never come out of here alive,' said one of the victims shortly before the attack, `but our deaths will not be in vain; they will bring forth new fighters, new triumphs, and our blood will come to haunt the guilty.'

He may be right. Killing prisoners feeds the legend of Sendero without damaging its military capacity. Besides, few guerrillas are ever captured since the army is unable to penetrate Sendero's secret cell structure and does not know who most of the leaders are. 'The intelligence service hasn't got a clue what it's doing,' said a diplomat. `Most seizures are just routine police work: they grab a guy, interrogate him, put his testicles in a vice, and sure enough every now and then they get a Senderista.' Not that they learn very much when they do. Captured guerrillas rarely betray the cause, and die under torture with Maoist maxims forever on their lips. Nor do journalists know much about them. Unlike other rebel movements in Latin America, which employ advertising agencies and at least pretend to be demo- crats, Sendero doesn't care what the world thinks. Guzman launched his insurgency on 18 May 1980, the very day when Peru was returning to democracy after 12 years of military rule. Fighting in the rugged mountains of Ayacucho his men soon gained fame as 'Poi Pot' fanatics. Electric- ity was cut and tractors were burnt to fight `imperialist technology'; symbols of a cor- rupted world. Rural markets were closed in order to stamp out money and return to the barter system of the Incas. And peasants were told to grow only enough food for their own subsistence. It is not known whether these extremes have been merely tactical, part of a Maoist war of starving the enemy and 'surrounding the cities from the countryside', or whether they reflect Sendero's vision of the future. Most likely it is a mixture.

The Chinese have disowned them. The Russians and Americans are both targets of attack. 'The imperialist superpowers, the USA and USSR, invade, undermine, destroy, and try to drown everything in fear,' said Guzman in his only known speech, tut the people rear up ,they rise in rebellion and seize the reactionaries by the throat, tearing at them, and throttling them to death.' It is suitable language since that is more or less how Sendero fights: with its hands, with knives, and with machetes. Only on special raids do they use rifles or stolen dynamite stuffed into coca cola cans and hurled from slings.

But though it is a home grown move- ment it is not strictly an 'Indian revolt'. `Sendero has nothing to do with Andean traditions,' says Urrutia, 'beyond the trap- pings of Quechua culture it is utterly foreign.' Many of the early guerrillas were mixed blood mestizos rather than Indians. They were poor, but not the very poorest, and were educated beyond the capacity of Peru's depressed economy to absord them. Their commanders were white intellectuals who learnt Quechua because they saw Indian support as the key to revolution, but who showed scant respect for local custom. Village leaders were replaced by young Sendero supporters, defying the Indian esteem for elders, and children were kidnapped for indoctrination. Even so some Indians have sided with Sendero. 'They have understood the les- son,' says Guzman; 'nothing will be given to them: they can expect nothing from the law.' Those who don't understand, or who accept their lot out of deference or fear, have to be forced. If they resist they are beaten, mutilated, or murdered. Local officials have their throats cut after 'popu- lar trials' in the village square. Not even Communist mayors from the United Left coalition are spared. Guilty of 'parliamen- tary cretinism' they are singled out for execution. Sendero Luminoso, says the human rights body Americas Watch, 'is the most brutal and vicious guerrilla organisa- tion that has yet appeared in the western hemisphere.' The army is no better. In 1982 President Belaunde, who at first had scoffed at Sendero, declared a state of emergency and put Ayacucho under direct military rule, since then over 8,000 people have died, many of them seized by the security forces and found later in mass graves. `Whenever there's a killing," explained a peasant leader in the village of Palma Pampa, 'they always blame Sendero, but often it's really the army.' His comunity formed a civil defence force in 1984, not, he admitted, because they were especially hostile to Sendero but 'so that the army wouldn't suspect us of being terrorists'. Now his men go out on patrols in search of guerrillas, doing the army's dirty work, and fighting fellow Indians. `Two enemy forces, one Asiatic and the other Occidental, are fighting out their bloody and fratticidal war in Indian terri- tory,' fumed 'an editorial in Peru's Indian magazine Pueblo Indio, 'with the man- ipulation and massive slaughter of Indian people, innocent victims of a war that is not their own.'

The Occidentals are winning. Made to take sides, the peasants have yielded to the modernised brutality of the army, the force majeure of guns and helicopters. But that is not the end of the story. 'If you put your hand in a plate of mercury, it squeezes out all over the place,' said a diplomat; 'that's what the army had done with Sendero.' The guerrillas, having lost their hinterland but not their secret organisation, have turned to urban terrorism.

Blackouts, bombs, and assassinations have led to a nightly curfew in Lima and spoilt the socialist fiesta of President Alan Garcia. But through Sendero can still disrupt with impunity it seems to be on the wane . An exotic movement, far removed from the bustle of daily life, it is unlikely to gain support in the cities. While in the countryside it has left a trail of bitterness.

`There is great injustice here, great pover- ty,' said a rural school teacher in Ayacucho, 'and we would support a guer- rilla movement that respected us, that offered us a future, but it would have to be something totally different, with a new structure, a new name, a new everything. We will never support Sendero Luminoso again.'

Previous page

Previous page