Gone to pot

A. N. Wilson

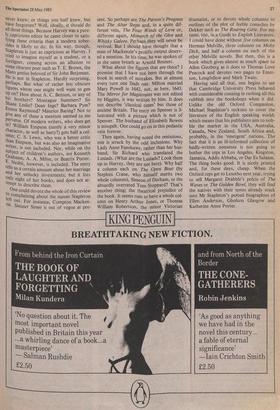

The Cambridge Guide to English Literature Michael Stapleton (Cambridge £15) it Paul Harvey's Oxford Companion e

English Literature is a wholly distinctiv .to volume, representing the eccentric range of LI its compilers' tastes and knowledge. He i finished it in 1932, and although it has been updated once or twice since, it is really ir- replaceable. It contained resumes of most of the novels of Trollope, Dickens, Scott and Henry James. At the same time it was irrelevantly, and pleasingly, scattered With miscellaneous gastronomic or military lore. There is an entry on the `Lutine bell' and on the lines of Torres Vedras, as well as ex- planations of Goliardic verse ana assessments of such semi-forgotten figures of the operatic world as Madam Vestris. An hour with Harvey is guaranteed to tell y°,1 something you did not know already. It's also bound to be amusing. I believe that Oxford University Press are now going to ditch Harvey's Companion, le and that they have hired Margaret Dr.abb to do a new one. Probably it will aim a.' being more accurate or comprehensive, but Ite is unlikely to be so entertaining. Cambrulg., University Press are not prepared to wan, and see. They have rushed out a Guide co their own, edited by Michael Stapleton.. Should a work of reference ai m at you things you know already; or things yo never knew; or things you half knew, but have forgotten? Well, ideally, it should do all three things. Because Harvey was a pure- 1Y capricious editor he came closer to satis- fying these criteria than a modern sober- sides is likely to do. In his way, though, Stapleton is just as capricious as Harvey. I tried to imagine myself as a student, or a foreigner, coming across an allusion to some obscure poet such as T. E. Brown, the Manx genius beloved of Sir John Betjeman. He is not in Stapleton. Hardly surprising, Perhaps. But what of rather less obscure figures whom one might well want to gen 013 on? How about A. C. Benson, or any of his brothers? Montague Summers? Sir Shane Leslie? Dean Inge? Barbara Pym? Ernest Raymond? Maurice Baring? Not to give any of these a mention seemed to me perverse. Of modern writers, who does get in? William Empson (surely a very minor character as well as batty?) gets half a col- umn; C. S. Lewis, who was a better critic than Empson, but was also an imaginative writer, is not included. Nor, while on the subject of children's authors, are Kenneth Grahame, A. A, Milne, or Beatrix Potter. E. Nesbit, however, is included. The entry tells us a certain amount about her marriage and her unlucky investments; but it lists only eight of her books, and does not at- tempt to describe them.

One could devote the whole of this review 1-.0 complaining about the names Stapleton left out. For instance, Compton Macken- zie. Sinister Street is out of vogue at pre- sent. So perhaps are The Parson's Progress and The Altar Steps and, in a quite dif- ferent vein, The Four Winds of Love or, different again, Monarch of the Glen and Whisky Galore. Perhaps they will never be revived. But I should have thought that a man of Mackenzie's prolific output deserv- ed a mention. In his time, he was spoken of in the same breath as Arnold Bennett.

What about the figures that are there? I promise that I have not been through the book in search of mistakes. But at almost every turn one finds one. Milton married Mary Powell in 1642, not, as here, 1643. The Mirror for Magistrates was not edited by Higgins, it was written by him. It does not describe 'classical times' but those of ancient Britain. The entry on Spenser is il- lustrated with a picture which is not of Spenser. The husband of Elizabeth Bowen is misspelt. One could go on in this pedantic vein forever.

Then again, having noted the omissions, one is struck by the odd inclusions. Why Lady Anne Fanshawe, rather than her hus- band, Sir Richard who translated the Lusiads. (What are the Lusiads? Look them up in Harvey, they are not here). Why half a column each on The Open Boat (by Stephen Crane, who himself merits two whole columns), Simeon of Durham, or the absurdly overrated Tom Stoppard? That's another thing; the theatrical prejudice of the book. It seems rum to have a whole col- umn on Henry Arthur Jones, or Thomas William Robertson, the minor Victorian dramatist, or to devote whole columns to outlines of the plot of feeble comedies by Dekker such as The Roaring Girle. For my taste, too, in a Guide to English Literature, I could have done without five columns on Herman Melville, three columns on Moby Dick, and half a column on each of the other Melville novels. But then, this is a book which gives almost as much space to Allen Ginsberg as it does to Thomas Love Peacock and devotes two pages to Emer- son, Longfellow and Mark Twain.

Having said all that, one begins to see that Cambridge University Press behaved with considerable cunning in rushing all this rubbish into the bookshops when it did. Unlike the old Oxford Companion, Michael Stapleton's reckons to cover the literature of the English speaking world; which means that his publishers aim to nob- ble the market in the USA, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa and, probably, in the 'emergent' nations. The fact that it is an ill-informed collection of badly-written nonsense is not going to bother the reps in Los Angeles, Kingston, Jamaica, Addis Abbaba, or Dar Es Salaam. The thing looks good. It is nicely printed and, for these days, cheap. When the Oxford reps get to Lesotho next year, trying to sell Margaret Drabble's precis of The Waves or The Golden Bowl, they will find the natives with their noses already stuck into Mr Stapleton's potted biographies of Ellen Anderson, Gholson Glasgow and Katherine Anne Porter.

Previous page

Previous page