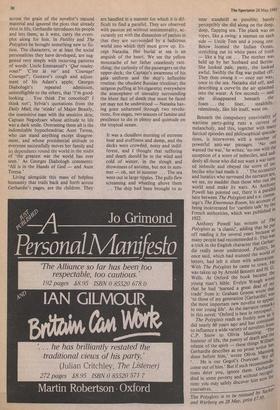

William Gerhardie

Michael Holroyd

William Gerhardie was 29 when The Polyglots was first published in 1925. Like his first novel, Futility, it draws largely on personal experiences. The son of a suc-

cessful British industrialist living in St Petersburg, and his Yorkshire wife, Gerhar- die had been considered the dunce of the family and was sent to England in his late teens to be trained for what was called 'a commercial career.' But he detested com- merce and dreamed only of the dramatic triumphs with which he hoped to take the London theatres by storm. To improve his English style he was studying Wilde; and an elegant cane, long locks and a languid ex- pression were parts of his literary make-up at this time.

During the war he was posted to the staff

of the British Military Attache at Petrograd and, arriving there with an enormous sword bought second-hand in the Charing Cross Road ('le sabre de mon pere — a long clum-

sy thing in a leather scabbard' that makes a

momentary appearance in Uncle Lucy's funeral procession in The Polyglots), he

Was welcomed as an old campaigner. The Russian Revolution sent Gerhardie back to

England. But in 1918 he set out again, and after crossing America and Japan reached Vladivostok, where the British Military

Mission had established itself. After two Years in Siberia, mostly in the company of generals, he left the army with an OBE and two foreign decorations, sailing home by Way of Singapore, Colombo and Port Said a journey that forms the closing chapters of The Polyglots.

The Polyglots is the narrative of a high- spirited egocentric young officer who

comes across a Belgian family, rich in ec- centrics, to whom he is related and with

Whom he lives while on a military mission to th e Par East. There arc obvious parallels here with Gerhardie's own life. His impres- sions of the First and Second Revolution in

Petrograd and the Allied Intervention in

business during 1918-20, of the whole business of interfering on an international scale in other people's affairs, are recorded here and in Futility.

On returning to England, Gerhardie went to Worcester College, Oxford. Though he was responsive to the beauty of Oxford, his

°Plmori of academic life was not high and is Probably reflected in the Johnsonian state-

ment of the narrator in this novel: 'There are as many fools at a university as

elsewhere ... but their folly, I admit, has a certain stamp — the stamp of university

aining if you like. It is trained folly.'

After leaving Oxford, Gerhardie wrote much of The Polyglots at Innsbruck. He completed it under difficult conditions While his father was dying. His mother

would read out pages from the manuscript to the old man `to kill time', and for the most part he listened without comment, though occasionally pronouncing some passage to be 'instructive'. But when she came to the sea-burial of Natasha, she began to cry, and this bothered him. 'Don't cry,' he urged. 'It's not real. Willy has in- vented it.'

The narrator in The Polyglots has by the end of the novel decided to write the novel we are reading. 'I have already written the title page,' he announces in answer to his Aunt Teresa's query as to what they are go- ing to do for money. 'Is it going to sell well?' she demands; and the narrator notes, `I was silent.'

On The Polyglots were pinned the fami- ly's hopes of re-making the family fortune, but Gerhardie's father died a few months before publication. The book did make Gerhardie's name as a novelist; but as to fortune, he later calculated that, contrary to expectation, it had brought in `something equivalent, in terms of royalties, to nothing,' In later years Gerhardie was to adopt as his colophon the ampersand. None of his novels display with more skill and vitality the peculiar inclusiveness of his philosophy, and no happier narrator ever adopted the first person singular, Captain Georges Hamlet Alexander Diabologh is a young man with literary aspirations. He labours intermittently at a work whose title, Record of the Stages in the Evolution of an At- titude, suggests the theme (`the central thing round which the world revolved') of The Polyglots. Our attitude to life, Gerhar- die implies, is the same as our attitude to fiction which is born of our experience of life. When Sylvia, on board the Rhinoceros, wants to know what will hap- pen after they get back to Europe, the nar- rator replies that he has noticed, with regret, 'the same morbid and unhealthy ap- petite in the readers of novels.' And later, now the author of this novel, he asks us to co-operate with him —financially (by buy- ing several copies to help the fortunes of the characters about whom we have been reading) and imaginatively 'in a spirit of good will.' The book stands, the readers evolve.

It is in the orchestration of contradictory moods and attitudes that The Polyglots ex- cels: though it owes something to Chekhov (about whom Gerhardie wrote a brilliant lit- tle book at Oxford), the tone is original and unmistakable: 'personal, light and glanc- ing, often lyrical but always self-deflating' as Walter Allen described it. Believing that the invention of psychologically convincing characters and well-balanced plots cut across the grain of the novelist's natural material and ignored the plots that already exist in life, Gerhardie introduces his people and lets them, as it were, carry the event- plot along for him. In Futility and The Polyglots he brought something new to fic- tion. The characters, or at least the social personalities they have developed, are sug- gested very simply with recurring patterns of words: Uncle Emmanuel's 'Que voulez- vous?"C'est la vie' and 'Courage! Courage!'; Gustave's cough and adjust- ment of his Adam's apple; Georges Diabologh's repeated admission, unintelligible to the others, that 'I'm good- looking ... You think I'm conceited? I think not'; Sylvia's quotations from the Daily Mail; the 'stinks' of Major Beastly, the insensitive man with the sensitive skin; Captain Negodyaev whose attitude to life was a dark smile. Overseeing them all is the indomitable hypochondriac Aunt Teresa, who can stand anything except disagree- ment, and whose presidential attitude to everyone successfully moves her family and its dependants round the world in the midst of 'the greatest war the world has ever seen.' As Georges Diabologh comments: `All is in the Hands of God — and Aunt Teresa.'

Living alongside this mass of helpless humanity that trails back and forth across Gerhardie's pages, are the children. They are handled in a manner for which it is dif- ficult to find a parallel. They are observed with passion yet without sentimentality, ac- curately yet with the dimension of pathos in that they are surrounded by a ludicrous world into which they must grow up. Ex- cept Natasha. Her burial at sea is an anguish of the heart. We see the yellow moustache of her father ceaselessly twit- ching; the curiosity of the passengers on the upper-deck; the Captain's awareness of his gala uniform and the ship's inflexible routine; the obsolete Russian tricolour; the surgeon puffing at his cigarette; everywhere the atmosphere of unreality surrounding the blunt fact of death that must be faced yet may not be understood — Natasha hav- ing gone unharmed through two revolu- tions, five sieges, two seasons of famine and pestilence to die in plenty and quietude on the tropical ocean.

It was a cloudless morning of extreme heat and stuffiness and damp, and the decks were crowded, noisy and indif- ferent, and I thought that suffering and death should be in the wind and cold of winter, in the slough and drowsiness of autumn, but not in sum- mer -- oh, not in summer ... The sea went out in large ripples. The gulls flew screaming and wheeling above them ... The ship had been brought to as

The Spectator 28 May 1983 near standstill as possible; barely perceptibly she slid along on the deep, deep, flapping sea. The plank was on ropes, like a swing: a seaman on each side — Uncle Tom and a young one. Below loomed the Indian Ocean, stretching out its white paws of froth — like a big cat ... The mother was held up by her husband and Berthe. She looked pale, pasty, she looked awful. Swiftly the flag was pulled off. They then swung it — once our way, once to the sea. Natasha slid off, and describing a curve in the air splashed into the water. A few seconds — and she disappeared beneath the

foam ... the liner, ily relentlessly, like life itself, we Beneath the compulsory conviviality of

stealthily, o ltnh. , wartime party-going runs a current of melancholy, and this, together with manY farcical episodes and philosophical specula- tions, is interwoven with a number of powerful anti-war passages. 'No one Wanted the war,' he writes; 'no one with the exception of a score of imbeciles, and sud- denly all those who did not want a war turn- ed imbecile and obeyed the score of im- beciles who had made it ... ' The eccentrics and lunatics who surround the narrator are, we see, no madder than those who run the world amd make its wars. As Anthony Powell has pointed out, there is a parallel here between The Polyglots and e. e. anul ings's The Enormous Room, his account of being incarcerated for 'careless talk' by the French authorities, which was published In 19 Anthony Powell has written of The Polyglots as 'a classic', adding that he put so off reading it for several years because many people had recommended it. This was a trick in the English character that Gerlia,r, of die really never understood. Futility, h,. once said, which had stunned the world 11! letters, had left it silent with admiratio_e With The Polyglots he came to town. 11,. was taken up by Arnold Bennett and H. the Wells. At Oxford the book became he young man's bible. Evelyn Waugh wrote of 111Y that he had 'learned a great deal trade' from it: Graham Greene wrote_ was [hat to those of my generation [Gerhardie] the most important new novelist to appaerro

r in our young life'. As the narrator in this novel: 'Oxford is best in retrosp

The Polyglots reads as freshly now as did nearly 60 years ago and has cont 1n ed to influence a wide variety of novelists C.P. Snow to Olivia Manning: and the humour of life, the poetry of death V4. telrintlaas

release of the spirit — these things Gerhardie describes as no prose wrian done before him,' wrote Olivia M

• • He is our Gogol's Overcoatni• niWenura_ come out of him.' But if such recoGerhardie r ecoe,'; tions deter you, ignore them.

now i"

died in some poverty and without ytioounr:seylovuesmay safely discover Secker aTnhde oa Polyglots a ins 2t 8o mbeayreipssieiuceed

Previous page

Previous page