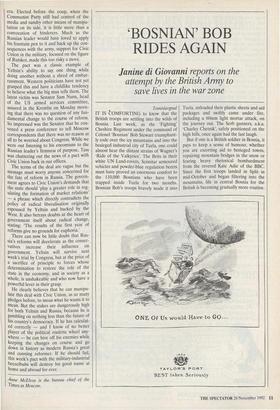

`BOSNIAN' BOB RIDES AGAIN

Janine di Giovanni reports on the

attempt by the British Army to save lives in the war zone

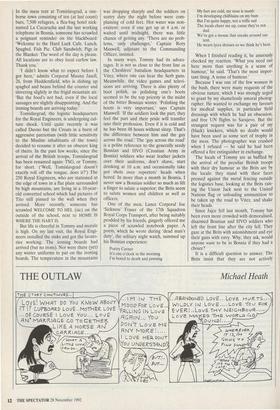

Tomislavgrad IT IS COMFORTING to know that the British troops are settling into the wilds of Bosnia. Last week, as the 'Fighting' Cheshire Regiment under the command of Colonel 'Bosnian' Bob Stewart triumphant- ly rode over the icy mountains and into the besieged industrial city of Tuzla, one could almost hear the distant strains of Wagner's `Ride of the Valkyries'. The Brits in their white UN Land-rovers, Scimitar armoured vehicles and powder-blue regulation berets must have proved an enormous comfort to the 110,000 Bosnians who have been trapped inside Tuzla for two months. Bosnian Bob's troops bravely made it into Tuzla, unloaded their plastic sheets and aid packages and swiftly came under fire, including a 60mm light mortar attack, on the journey out. The Serb gunners, a.k.a. `Charley Chetnik', safely positioned on the high hills, once again had the last laugh.

But if one is a British soldier in Bosnia, it pays to keep a sense of humour, whether you are escorting aid to besieged towns, repairing mountain bridges in the snow or fearing heavy rhetorical bombardment from the revered Kate Adie of the BBC. Since the first troops landed in Split in mid-October and began filtering into the mountains, life in central Bosnia for the British is becoming gradually more routine. In the mess tent at Tomislavgrad, a one- horse town consisting of ten (at last count) bars, 7,500 refugees, a flea-bag hotel nick- named La Cucaracha and the last working telephone in Bosnia, someone has scrawled a poignant reminder on the blackboard: `Welcome to the Hard Luck Cafe. Lunch. Spagbol. Fish Pie. Club Sandwich. Pigs in the Blanket. The word of the day is please. All locations are to obey local curfew law. Thank you.'

'I didn't know what to expect before I got here,' admits Corporal Mauna Jasell, 26, from Huddersfield, who is dishing up spagbol and beans behind the counter and shivering slightly in the frigid mountain air. 'But the food's not bad, even if the local sausages are slightly disappointing. And the ironing boards are arriving today.'

Tomislavgrad, the logistic headquarters for the Royal Engineers, is undergoing cul- ture shock. Until quite recently it was called Duvno but the Croats in a burst of aggressive patriotism (with little sensitivity to the Muslim inhabitants of the town) decided to rename it after an obscure king of theirs. In the past few weeks, since the arrival of the British troops, Tomislavgrad has been renamed again: TSG, or Tommy, for short. ('Well, Tomislavgrad doesn't exactly roll off the tongue, does it?') The 250 Royal Engineers, who are stationed at the edge of town in a flat plain surrounded by high mountains, are living in a 10-year- old converted school which had pictures of Tito still pinned to the wall when they arrived. More recently, someone has scrawled WELCOME TO HEL (sic) on the outside of the school, next to HOME IS WHERE THE HART IS.

But life is cheerful in Tommy and morale is high. On my last visit, the Royal Engi- neers installed the sinks and got the lavato- ries working. The ironing boards had arrived (but no irons). Nor were there (yet) any winter uniforms to put on the ironing boards. The temperature in the mountains was dropping sharply and the soldiers on sentry duty the night before were com- plaining of cold feet. Hot water was non- existent: even if one got up at 4 a.m. or waited until midnight, there was little chance of getting any. 'There are no prob- lems, only challenges,' Captain Rory Maxwell, adjutant to the Commanding Officer, insisted.

In many ways, Tommy had its advan- tages. It is not as close to the front line as the Cheshires' battalion headquarters in Vitez, where one can hear the Serb guns. Meanwhile, the video games and televi- sions are arriving. There is also plenty of boot polish, as polishing one's boots seemed to be the top priority in the midst of the bitter Bosnian winter. 'Polishing the boots is very important,' says Captain Maxwell. 'If the soldiers look the part, they feel the part and their pride will transfer into their profession. Even if it is cold and he has been 48 hours without sleep. That's the difference between him and the guy across the road.' The 'guy across the road' is a polite reference to the generally seedy Bosnian and HVO (Croatian Army in Bosnia) soldiers who wear leather jackets over their uniforms, don't shave, start drinking at 10 a.m. and occasionally take pot shots over reporters' heads when bored. In more than a month in Bosnia, I never saw a Bosnian soldier so much as lift a finger to salute a superior; the Brits seem to salute women and children as well as officers.

One of the men, Lance Corporal Joe 'Sickness' Fraser of the 17th Squadron Royal Corps Transport, after being suitably prodded by his friends, gingerly offered me a piece of scrawled notebook paper. A poem, which he wrote during 'dead man's duty', the solitary night watch, summed up his Bosnian experience: Poetry Corner It's one o'clock in the morning I'm bored to death and yawning My feet are cold, my nose is numb I'm developing chilblains on my bum But I'm quite happy, not a trifle sad The locals cheer me up, cause they're not dad.

We've got a mouse that sneaks around our tent.

He wears lycra dresses so we think he's bent.

When I finished reading it, he anxiously checked my reaction. 'What you need out here more than anything is a sense of humour,' he said. 'That's the most impor- tant thing. A sense of humour.'

Because I was one of the few women in the bush, there were many requests of the obvious nature, which I was strongly urged to grant by my shamelessly amoral photog- rapher. He wanted to exchange my favours for medical supplies, in particular field dressings with which he had an obsession, and free UN flights to Sarajevo. But the strangest request was for a pair of my (black) knickers, which no doubt would have been used as some sort of trophy in the mess. The photographer was crushed when I refused — he said he had been offered a fire extinguisher in exchange.

The locals of Tommy are as baffled by the arrival of the peculiar British troops with their dry humour as the Brits are by the locals: they stand with their faces pressed against the metal fencing outside the logistics base, looking at the Brits rais- ing the Union Jack next to the United Nations flag or unloading ammunition to be taken up the road to Vitez, and shake their heads.

Since Jajce fell last month, Tommy has been even more crowded with demoralised, disarmed Bosnian and HVO soldiers who left the front line after the city fell. They gaze at the Brits with astonishment and eye their guns with envy. Why, they ask, would anyone want to be in Bosnia if they had a choice?

It is a difficult question to answer. The Brits insist that they are not actively involved in the war and are only on a peace-keeping mission. But, as any soldier who has come under fire can attest, it is difficult not to be dragged into the quag- mire of the conflict and thus become a part of it. Within days after the advance party of troops arrived in mid-October, the Brits were caught up in the vicious internecine Muslim-Croat fighting in Novitravnik. When Prozor, a mainly Muslim town, was destroyed by Croats last month, British sol- diers riding through saw bodies on the street and witnessed Croatian soldiers loot- ing Muslim shops. Two weeks ago, Brits on a recce mission opened fire for the first time when Charley Chetnik aimed at a British convoy en route between Vitez and Tuzla. Three British Land-rovers came under fire from rifles, heavy machine-guns and light mortars. One Land-rover was hit and the Brits returned with covering fire.

Ten days before that, near Turbe, a BBC cameraman was killed by an anti-aircraft missile as he was travelling alone in his armoured car to film the flood of refugees escaping from Jajce. I was standing in the HVO headquarters in Travnik when a spe- cial party brought his body, his blood-splat- tered camera and his helmet back. As Croatian soldiers argued over procedure, I stood outside with the shoeless corpse and with Josip, a distraught soldier who had crawled for two hours on his stomach under sniper fire in an attempt to rescue the journalist. As we searched through the cameraman's kit for some kind of identifi- cation, Josip suddenly exploded with rage. `What you Brits do not seem to under- stand,' he said vehemently, 'is that they will shoot at anything that moves. Journalists. United Nations. British soldiers. You think you are so different? You think an armed car or a passport makes a difference?'

A passport or a light blue United Nations flag certainly does not make a dif- ference. Colonel Bob Stewart, a veteran of Northern Ireland, understands the conflict and knows the roads well, but has a gung- ho 'We are here to do our job' attitude which sounds a bit out of place in the Wild West of Bosnia where no rules apply. 'If someone deliberately fires at my soldiers the rules of engagement are likely to allow me to fire back and quickly,' he said when he arrived. `So please don't fire at me. We are not here to open fire but to save lives.' The Brits are in Bosnia to do good work, to bring aid to besieged cities, but to the Serb gunners on the high positions they are moving targets like everybody else.

The rank and file soldiers are also con- vinced that they are here to save Bosnian lives, but their sense of adventure is mixed with confusion and a natural and very wise sense of fear. Before they left Germany, some were given brief lectures and map readings, as well as training in specific win- ter conditions, but many are understand- ably bewildered by the increased ethnic fighting. They know this is not their war, and most of the time, they cannot even tell who is shooting at whom. 'Was that a Croat? Or a Bosnian? Maybe it was a Mus- lim,' was one of the first responses after the Novitravnik fracas.

Corporal Mark Lobley of the Royal Engineers, who was in the Novitravnik recce party a short time after his arrival from Germany, recalls the confusion: `When you see a row of anti-tank mines at checkpoints, it's a bit of a shock,' he says. `In the Falklands, you knew what was hap- pening, who was the enemy. Here it changes as you drive down the road. We haven't got an enemy. It makes it hard to understand. One day you're working together. The next day you're the worst of enemies.'

There is also the constant reminder of the devastation of the war. Even in Tommy, further from the front line than Vitez, there is the badly equipped hospital packed with mutilated and injured, and ambulances carrying the dead. After Jajce fell, the trail of refugees flooding down the mountain road on donkey carts, clutching burlap sacks, was a testament to the devas- tation. 'I would like to see all of us come back from this war, but I don't think it's going to happen,' says Lance Corporal Darren 'Dingle' Bell, 23 from Hillingdon, Middlesex. "This territory is more danger- From THE GREAT AG E eic Port Prialfrnsi

ous and I couldn't tell a Serb from a Croat. What's really worrying is that anyone can take a shot at us.' His friend, Colin `Chaka' Khan, 28, from Fulham, is more concerned about the rules of engagement: that the British troops cannot fire until fired upon. 'I was a boxer,' he says. 'I wouldn't stand in the ring unless I was going to throw a punch. Here, we're going in not allowed to punch first; and the first punch that comes from them could be the knockout.'

Janine di Giovanni writes for the Sunday Times.

Previous page

Previous page