THE LESSON WE CAN LEARN

There is no schools apartheid across the Channel. Rachel Johnson says

the middle classes on the Continent cannot understand why we risk ruin to pay for our children's education

Brussels CONSTANCE has just returned from a school day-trip to inspect some Gallo- Roman ruins near Aubechies. At the time of writing, Guy is still away in Eupen, near the German border, for his week of autumnal classes vertes, during which he is to `s'emerveiller de nature' and 'discover silence', sleeping for five nights in a log cabin that he and his classmates have erected themselves. Connie is an English child of two and a half. Guy, Anglo-Bel- gian, is four.

Don't get me wrong. This is not about paedophilia or pre- cocity. Their mothers couldn't have been happier (their only qualms concerned the lack of seat belts on the buses and the regulation hint of Stella Artois on the drivers' breath). No, the point of these vignettes is to illustrate a reality that English parents, many strug- gling to meet school fees that are rising by 6.3 per cent annually, may find disturbing.

These two moppets are both enrolled in Belgian state schools, part of an entire par- allel universe of education that exists almost everywhere in Europe but Britain. Guy's and Connie's two schools are not only free; they are also the kind of schools to which you would be delighted to send your children.

Imagine a society where parents do not crucify themselves with anxiety about not `doing the best by their child' if they send them to the local comprehensive, or guilt if they opt to go private — a selfish but understandable choice given that 92 of the top 100 schools in the country, as deter- mined by A-level results, are independent. Imagine a society where people pay more in tax and social security but are excused the obligation of shelling out vast sums to ensure their child makes it to a top univer- sity (state schools in Britain educate 93 per cent of the pupils, produce 67 per cent of the necessary qualifications, but still get only 48 per cent of the places). Imagine a society where no one drones on about schools at dinner parties. This is not Utopia. This is the norm across Europe.

`The advantage for those who can afford private education, and the disadvantage for those who cannot, has no parallel in any other advanced country,' says Peter Lempl, founder of the Sutton Trust, the aim of which is to open up 'elite education' in the UK.

So why has Britain alone made such a horlicks of it? Strangely enough, it doesn't seem to be that we spend too little on edu- cation, as a nation. We spend more on our education than Germany, the Netherlands and Japan.

The answer seems to be this: we are not the only country in Europe which has 'pri- vate' schools but we are the only one that has an established, competitive network of independent schools for which parents are privileged to pay out of taxed income. No other country has a comparable private sec- tor, for the simple reason that in most other EU countries although there is some sort of `private' sector (which means state-sub- sidised and independently run), this is dwarfed by the efficient monolith of a cen- tralised state system.

As Philip Mende, a Berliner working at the British embassy, tells me, 'a fee-paying school such as you find in England would be seen as elitist in Germany, where the elites collapsed after two world wars and these schools collapsed with them. None of the parents would now support such a system.'

There is a different philosophy, a differ- ent ideology here. Schooling in most other northern European countries is designed to promote egalite, while the independent sector in Britain exists, in part, to perpetu- ate an elite. The proportion of Law Lords, bishops, ambassadors, company directors, chairmen of merchant banks, medical con- sultants and so on who have not been to public school and Oxbridge is still pretty meagre, as A Class Act, by Andrew Adonis and Stephen Pollard, recently documented.

`Quality in education is the government's big priority,' says Jane Marshall. 'They're very proud of their education here, and teachers are civil servants, trained and tenured.' Indeed, an old boast of parents is that the education is so perfectly tuned that seven-year-olds will be opening the same textbook at the same page at the same time in French /ycees as far apart as Helsinki and Beijing.

When I suggested in an article two years ago that the francophone system was clear- ly very rigorous (i.e. brutal) but not, per- haps, very nurturing, the Lycee Jean Monnet here in Brussels was so outraged that it threatened to send the French ambassador to protest to the British ambassador.

I managed to head off this demarche, and have since become too respectful of the francophone educational system to diss it again. How can I feel anything but admira- tion and envy for France, Belgium and all the other European countries that have proved it is possible to educate children to parents' satisfaction out of the public purse?

French /ycees and German Gymnasien have always existed to provide an education. The English public school existed to supply an imperial class, and Dr Arnold's personal vocation at Rugby was duly to instil religious and moral principles first, gentlemanly con- duct second, and, lastly, intellectual disci- pline. The English ideal was to sophronise; the European to scolariser.

On the Continent, character-building `factories for gentlemen' are thin on the ground. Belgium has various private academies for rich kids, the most famous being l'Abbaye de Maredsous, where par- ents pay a `minervar proportionate to their income; Salem in south Germany is a smart private school where Thomas Mann sent his children.

Otherwise, Eurotrash babes and those pedigreed in the Almanach de Gotha have to slum it in Le Rosey, the boarding school on the shores of Lake Leman in Switzer- land that is the alma mater of King Bau- douin, the former Shah of Iran, the Duke of Kent, Prince Victor-Emmanuel of Savoy and Prince Rainier of Monaco, as well as generation upon generation of Metter- nichs, Borgheses and Hohenzollerns.

Or they get sent to school in England, where there is, as a baffled French parent might put it, an embarras de choix. In Jan- uary 2000, the Independent Schools Infor- mation Service (Isis) recorded an intake of 8,000 children from overseas, a rise of 10 per cent on the previous year.

While tremendous cachet attaches to a privileged education in the UK or at Le Rosey, it really does appear that our fellow Europeans are largely content with what they've got: a state sector which delivers, from cradle (infants as young as six weeks can be placed in a state-funded crèche) to rave (more than 90 per cent of 16- to 18- year-olds attend school in Belgium, France, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden, compared with 70 per cent in Britain).

I asked an Austrian friend of mine, who (in common with almost all Germans and Austrians) attended a staatliche Schule, what she thought of the British two-tier system that bifurcates the country like a Berlin Wall. She surprised me.

`We all think that the boys do look very chic in their school uniform,' she said of Eton, stock images of which are always flashed up whenever the subject of our schools, Prince William, class system and so on are in the news. 'But we had no idea that it ruined the parents! That the whole family was clubbing together to pay the fees. When I heard for the first time what it cost I was absolutely amazed.'

Indeed, my Austrian friend might be even more amazed to hear that the average annual boarding fees currently stand at £13,341, while the average adult male salary in the UK is £20,919; Eton's annual fees are £15,660, but that is before the chic uniform and all the extras like beagling are thrown in. If you've ever wondered why it is that the standard of living is so much high- er on this side of the Channel, you may wish to ponder that statistic.

The question, though, that must torture all right-thinking British parents at some time or another is this: are we really stuck with a system that creams off 7 per cent of the children into the fee-paying elite, and allows the sediment of 93 per cent to settle in the state system? As I contem- plate moving back to Britain early next year, the choice that faces every aspira- tional British parent now faces my family too. Of course I believe there are excel- lent state schools and rotten private ones, and vice versa, but from this side of the Channel it looks like a choice between penury or second-best.

It seems primitive that the thrust of the debate is still in one direction, which is to open up the public schools (and the top universities) to those from the state sector. This is the aim of the Sutton Trust, which underwrites the fees of poor pupils at a Manchester private school, as it was the aim of the now disbanded Assisted Places Scheme. Why not put the social engine in reverse thrust, and persuade middle-class parents like me to use state schools instead? I asked the former Tory minister George Walden, who has written books on both education and elites, to tell me whether this could work here, as it does in Europe. Walden's message was miserably clear. Elsewhere in Europe, the dominance of one education system means there is never a second-best for parents or children. In Britain, there are two discrete educational cultures, and no impetus to swirl them together.

`The last two prime ministers have per- sonally assured me,' he answered, 'that they are determined to raise state educa- tion to a level where more parents want to use it. That is evasion. This is the one issue where the Left and the Right cannot tell the truth, which is that they both prefer the status quo, which is education by class and by cash.' Walden's children, he tells me, go to private school 'because we don't have proper state schools like they do in France'.

One is left hoping, in a muddled way, for the abolition of public schools, in the same futile way one hopes, when stuck in some monumental traffic jam, that the govern- ment would just get on with it and ban cars. But we know it won't happen, as the Labour party no longer even hints in its manifestos at removing the charitable sta- tus of the public schools.

There is nothing to be done about the existence of St Custard's, which Tony Crosland called the 'greatest single cause of stratification and class-consciousness in Britain'. The parents' right to choose the kind of education a child receives is enshrined in the 1948 declaration of human rights, as you only have to open an Isis handbook to find out.

And you only have to come to live in Belgium, or France, or Germany, or Den- mark, to see what a chiz it all is.

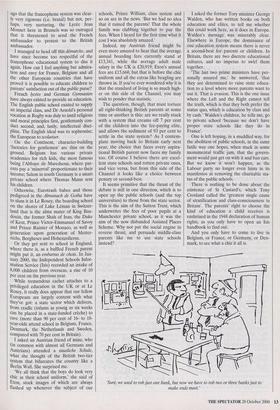

`Sure, we used to rob just one bank, but now we have to rob two or three banks just to make ends meet.'

Previous page

Previous page