A FAMILY AT WAR

Philip Delves Broughton on how his

relatives in Burma have been terrorised and impoverished by the military regime

BY the time the last of my grandmother's four sisters died in Rangoon in 1995, there was no one left to collect her body from the hospital. Thirty-three years of military rule had forced most of her sprawling fam- ily to leave Burma. The few left behind were at each others' throats over the last remnants of family property and too embittered to organise a funeral. Eventu- ally, after several days, one of her nephews travelled from San Francisco to bury her.

What has happened to my mother's fam- ily since 1962, when the military seized power in Burma, is just one of thousands of such stories to emerge from this depressing corner of Asia. It is by no means the worst or the saddest. When I think of James Mawdsley and his fearless confrontation with the Burmese authori- ties, I think of those who resisted, or those who fled; but also of those who were forced to make whatever compromises were necessary to survive under a cruel and capricious regime.

Under the blankets of isolationism and international indifference, the Burmese government has committed every crime imaginable, from ethnic cleansing, to forc- ing thousands into slave labour. Under the guise of the Burmese Way to Socialism, a country once rich in minerals, natural resources and intellect has been pillaged by its military rulers and driven to the bot- tom of the world's economic heap, where it scavenges around with the likes of Chad.

Still lording it over Burma is General Ne Win, no longer the official head of state, but still the true power in the land. A for- mer postal clerk, he led the 1962 coup and heaved Burma back towards the Dark Ages. Now 89, he lives in a mansion in Rangoon with his seventh wife, engulfed in a Papa Doc Duvalier kind of mystique.

An obsessive believer in astrology, Ne Win is driven by fear of some awful Bud- dhist retribution. When his astrologer told him that it was unlucky for cars in Burma to drive on the left, they were all moved over to the right. When his astrologer told him that the only way to avoid assassins was to dress as a king and fly above Ran- goon in a plane, he obeyed. He once aban- doned a trip to France when he was halfway there when advised that the stars foretold disaster in Paris.

He used to make frequent visits to Lon- don to see a psychiatrist, but those tailed off in the wake of General Pinochet's arrest. A more bizarre rumour is that he visits a clinic in Germany to have fresh blood transfused into his veins. He believes deeply in 'ye da ya chay', a Burmese expression which means taking precautions to ward off ill fortune. Rangoon's skyline is dotted with the golden towers of pagodas lavishly restored by Ne Win.

At the time of his coup, my great-grand- mother was the biggest film producer and cinema owner in Burma. She had married a French businessman, Louis Coombes, and they had nine children, including my grandmother. The family lived in a collec- tion of houses beside Rangoon's Inya Lake, the fanciest address in town. My mother, her sister and her brother grew up there, with one car assigned to each of them to bring tutors in and ferry them to and from school, and surrounded by cousins, 25 on her mother's side, 25 on her father's.

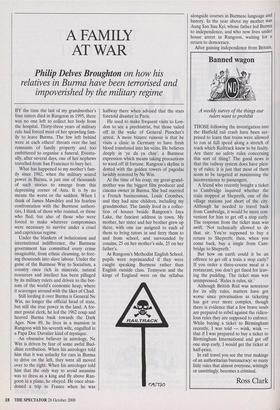

At Rangoon's Methodist English School, pupils were reprimanded if they were caught speaking Burmese rather than English outside class. Tennyson and the kings of England were on the syllabus alongside courses in Burmese language and history. In the year above my mother was Aung San Suu Kyi, whose father led Burma to independence, and who now lives under house arrest in Rangoon, waiting for a return to democracy.

After gaining independence from Britain, following the second world war, Burma was run by a representative government. Its main problem was keeping the country together as tribes in the north of the coun- try and south, towards the Thai border, fought to secede. The army used the ethnic Conflicts as the pretext for its coup. Promising to right the country and then return it to democracy, Ne Win proceeded to brutalise his opponents and grab what- ever businesses took his fancy, all in the name of socialism. Taking his lead, my grandmother's servants suddenly demand- ed to sit with the family at meals and refused to take orders. The family lost control of its businesses and, in the follow- ing years, began to drift apart. Democracy never came.

One of my great uncles, Arrizhad, was jailed for two years for sending a cheque to a businessman in Pakistan, a crime under the new isolationist regime. He entered prison a fat, jolly capitalist and emerged gaunt and broken by prison guards who at times forced him to eat his own excrement.

Some crossed the border to East Pak- istan, others fled to Australia, one lot even went to Norway. My mother's brother left for university in America and, a few years later, my aunt and grandparents followed, having smuggled out what money and jew- ellery they could in the linings of Thermos flasks. My mother married my father, an English missionary, as her family waited in Dacca for its visas to America. She found herself, aged 24, a vicar's wife in Northamp- ton, a long way from the Inya Lake.

It was a long, slow suffocation that Ne Win administered to Burma rather than a swift twist, and there were many who decided that it was worth sticking out. My great-uncle Maung Maung, an air force colonel who had trained at Cranwell, chose to stay and was rewarded with the ambassadorship to India. I remember going out to hold his golf clubs on a New Delhi course when I was eight years old. He idolised Jack Nicklaus. On his return to Burma, he became a preacher, touring churches with his Bible, a kind of penance, say most in the family, for what he had been part of.

His children also stayed and lived to regret it. I met them on my only visit to Burma in 1994. His eldest son, Tha Thoo, a qualified dentist, had seen his efforts at farming fail. He and his sisters lived in my great-grandmother's house, which was yel- lowing and rotten. Hammocks were tied up in the formal rooms and mangy dogs and random lovers ambled through the house.

Tha Thoo spoke the perfect English that all Burmese of his generation and class spoke, but he had no job and a dwindling inheritance. On our frequent outings for beer and cheroots, he would tell me that the only way to make money was to go into business with the military, and he had no desire to do that. Another of my mother's first cousins, Napoleon, had become a heroin addict. I visited him at his home in the slum on the outskirts of Rangoon. He could barely speak, and tossed back the cigarettes I had brought him. His mother, whose family had once been fabulously rich from manufactur- ing robes for Buddhist monks, sat in the corner playing with beads. Whatever she had not gambled away had been taken from her by the government. Beside her in an unopened box sat a brand-new television sent to her by her daughter, now living in California. It was going to be sold for cash.

I also met my mother's best childhood friend, Rosie, who unlike my mother had decided to stay in Rangoon. Her father had been a Rhodes Scholar and Burma's first post-independence ambassador to the United States. She and her husband were building a large new house when I met them, but their son John could not have been more depressed about having to live in it. Since 1988, when students led pro-democracy demonstrations across Burma, the universities have been open for only about a year in total. Only the military academies stayed open, meaning that only those who joined the army could receive any real further education. Like most of Burma's affluent young, John yearned to leave the cultural and intellec- tual graveyard of Rangoon and study abroad. My grandfather, who wakes up every morning at 5 a.m. in Washington, DC, to listen to the BBC World Service Asia news, says, 'There are no human beings left in Burma, just sheep led by the shep- herd.' James Mawdsley, who speaks encouragingly of the spirit of Burma's pro- democracy movement, would doubtless disagree. But my grandfather speaks as one who remembers Burma before it was put to sleep.

When I was in Rangoon, I stayed with my great-aunt Colleen, the one whose body lay unclaimed for days. She lived in a sky-blue mansion, surrounded by servants. On Satur- day mornings, a distant cousin of hers, an important army officer and government minister, would stop by her house to say hello before heading for the golf course. She would receive him sitting under por- traits of her mother and Louis Coombes.

Some in the family said she stayed in Rangoon simply to harvest all that her family had left behind. Whatever the case, she survived through luck and cun- ning. After her death, it emerged that years earlier she had handed over her businesses to a Chinese businessman who lived next door. Her only condition was that her lifestyle should not suffer until she died. Her real fortune, however, which she hid from everyone, was her jewellery. With no one left to give it to, she donated it to a local convent.

Previous page

Previous page