Reviews of the Week

• The Worm at the Root Leslie Stephen. By Noel gilroy Annan. (MacGibbon and Kee. 2ss.) Mn. Ar■iNik has written a study-iii intellectual ecology. "It is worth while," he says, "seeing how Stephen was gathered into the main intellectual movements of his time and what contributions he made to the Victorian ethos. For in the labyrinth of his conceptions of right and wrong we shall find the man for whom we are searching." It is a biologist's view of biography, peculiarly appropriate for this Victorian agnostic whose evolution drew him from the priest- hood into dubiety. There is an environment—of ideas, of people. How did they condition the development of Stephen's thought ? But he was a person, idiosyncratic ; "men," notes Mr. Annan, "have certain temperamental strains which they cannot eliminate." How were the pressures of the environmment themselves conditioned by the character of the man they worked on ? In these terms Mr. Annan has composed a book whose sub-title, "His Thought and Character in Relation to his Times," suggests the careful but dull propriety of an official biography. In fact, it is manifestly the work of an alert, inquisitive and unabashed mind. - Mr. Annan has fought his way through the huge documentation of the period, but he is not content to serve up the mixture as before. One has the impression, all through the book, of a man making up his own mind ; he knows exactly what he is saying, and why. There is little that is superficially attractive for the biographer about the wintry, aloof figure of Leslie Stephen—his favourite wind, Birrell observed, was due east—but Mr. Annan's close engagement with his subject gives him something of Strachey's power to vivify without Strachey's ability to mislead.

"The key to Stephen's character is his effort to change himself." His childhood among the evangelicals of the Clapham Sect, his years spent in Cambridge where Mill's Logic eroded the volitions of the young as insidiously as does logical positivism today, his relations with the Grand Chams of Victorian doubt, Huxley, Tyndall, Thomas Hardy—all these environmental pressures drove him one way, symbolised in the picture of Hardy, late at night, witnessing by a solitary lamp on the reading-table of Stephen's study the deed whereby he renounced Holy Orders. Reason dictated its imperatives remorselessly, and duty must be done. His Alpine climbs, his•feats of walking, his steady grind as a writer, his dour and constant witness to agnosticism, his pained abhorrence of the sexual are all convincingly gathered by Mr. Annan under this head. But some- think rebelled—a hyper-sensitivity of nature to which all through his life he cried "Down, wanton, down." Indeed he is a perfect- example-of Mill's comment that analytic habits are "a perpetual worm at the root both of the passions and of the virtues ; and, above - all, fearfully undermine all desires, and all pleasures."

Mr. Annan's judgement is that Stephen's effort to conquer himself maimed him. He could hardly be described, like Mill, as a saint of rationalism : he never saw so clearly, never felt so bitterly the paralysis of the imagination and the affections induced by a disci- pline of logic, analysis, and "the pursuit of Truth." But if the overtones of suffering, the intense spiritual agony, are missing, nevertheless he bore his cross. Mr. Annan's investigation of this conflict between heart and head, between creature and environment, and its profit and loss for Stephen as thinker, as critic, as father . and as friend is perhaps the most subtle and interesting element of his book.

There is a relevant document in the case from which Mr. Annan has been able to quote at some length for the first time ; though Maitland, the official biographer, saw it he was not so free_to draw on it. This is the manuscript autobiography which Stephen wrote for his children towards the end of his life and to which, charac- teristically, they gave the name of the Mausoleum Book. In this account of his private affairs "guilt, wells from his pen." A long • life, filled with the " agenbite of inwit " runs out in the crocodile tears of sentimental self-depreciation. He had failed as a writer ; he had been unkind to his wife. Reason's imperative were, he feared, unanswered. The uncompromising young don whose "ideal among intellectual undergraduates was the hard-headed man who stood for no nonsense" has gone soft ; he is Mr. Ramsay of To The Lighthouse.

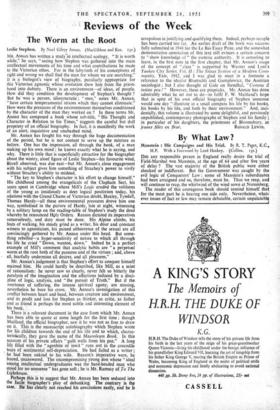

Perhaps this is to suggest that Mr. Annan has been seduced into the facile biographer's ploy of debunking'. The contrary is the case. He has clearly not reached his conclusions easily, and he Is scrupulous in justifying and qualifying them. Indeed, perhaps scruple has been Carried too far. An earlier draft of the book was success- fully submitted in 1948 for the Le Has Essay Prize, and the somewhat .demonstrative annotation of this text still evinces a certain concern to "show knowledge of" the esoteric authority. It is consoling to learn, in the first note to the first chapter, that Mr. Annan's usage of the concept of " class " is supported by Warner and Lunt's Yankee City Series, Vol. II: The Status System of a Modern Cont- munity, Yale, 1942, and I was glad to meet in a footnote a reference to the idealist Bluntschli and Gumplowicz, the Austrian sociologist ; but I also thought of Gide on Stendhal, "Comme il insiste peu ! " However, these are pinpricks. Mr. Annan has done admirably what he set out to do—to fulfil F. W. Maitland's hope that in spite of his own official biography of Stephen someone would one day "illustrate in a small compass his life by his books, his books by his life, and both by their environment." And, inci- dentally, this volume is illustrated by some delightful, and previously unpublished, contemporary photographs of Stephen and his family ; in particular of his daughters, the priestesses of Bloomsbury, as

Previous page

Previous page