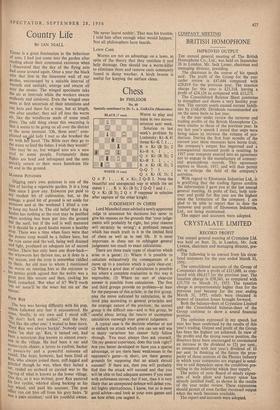

Chess

By PHILIDOR No. 69 Specially contributed by Dr. L. A. GARAZA (Montevideo) BLACK (7 men) Winn to play and mate in two moves: solution next week.

Solution to last week's problem by Loshinsky: Kt-K 4! threat Kt-K 7. 1 ... R x Kt (B 3); 2 Kt-B 6. 1 • , •

Q x Kt (B 3); 2 Kt-B 3. 1 . . . R x Kt (K 5); 2 Q—Q 7. 1

Q x (K 5); 2 Q x P. 1 . . . K x Kt; 2 Q-B 3. Note the beautiful and unexpected way in which the set mates 1 R x Kt (B 3); 2 Q-Q 7 and 1 .

Q x Kt (B 3); 2 Q x P reappear in solution after capture of the other knight.

JUDGEMENT IN CHESS

Lord Mansfield once advised a newly appointed Judge to announce his decisions but never to give his reasons on the grounds that 'your judge- ments will probably be right, but your reasons will certainly be wrong'; a profound remark which has much truth in it in the limited field of chess as well as in real life. It is most important in chess not to subjugate general judgement too much to exact calculation.

There are three main types of situation which arise in a game: (1) Where it is possible to calculate exhaustively the consequences of a move up to a position which is quite clear-cut; (2) Where a good deal of calculation is possible but where a complete evaluation in this way is Impossible; (3) Where no sort of clear-cut answer is possible from calculation. The first and third groups provide no problem—at least for the purposes of this article; in the first group, play the move indicated by calculation, in the third play according to general principles and the strategic nature of the position; the second group is the difficult one—and in this group, be careful about letting the results of incomplete calculation outweigh your general judgement.

A typical case is the decision whether or not to embark on attack which you can see will win in many variations but cannot fully follow through. You must always then ask yourself, 'On my general experience, does this look right'?' Are you better developed or have you a spatial advantage, or are there basic weaknesses in the opponent's game—in short, are there general grounds for supposing that an attack should succeed? If there are, then you will probably find that the attack will succeed and that you will be able to find adequate answers if you meet with unforeseen moves; but if not, then it is very likely that an unexpected defence will defeat you. All highly platitudinous, I know, but so is most good advice—and look at your own games and see how often you neglect it. WHITE (8 men)

Previous page

Previous page