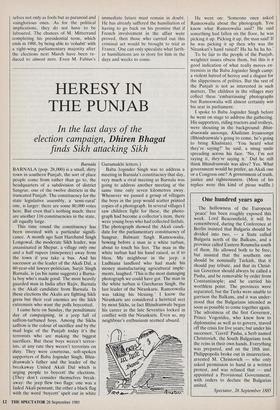

MITTERRAND'S FATAL COVER-UP

Sam White on the disaster

which France courted by sinking the Rainbow Warrior

Paris NEITHER the resignation last week of the Minister of Defence M. Charles Hernu, nor the sacking of the head of the overseas intelligence service Admiral Lacoste, nor finally the admission by the Prime Minister M. Laurent Fabius that it was French agents who sank the Greenpeace vessel Rainbow Warrior in Auckland harbour last July has served to reduce the political tension in France over the whole affair. It has on the contrary intensified it as the question is being more and more insistently asked: What was the level of political approval given to the operation? In other words, does the buck stop with Hernu or does it go higher? To everyone who has had ministerial experience it seems incon- ceivable that the secret service would have gone ahead with an operation without assuring itself of political clearance at the highest level. This can only mean the President or someone acting for him at the Elysee Palace. As it must be assumed that M. Mitterrand is too wise and mature a man to have given his approval to so dangerous and hare-brained a plot, it can only be concluded that a member of his entourage took it upon himself to give his approval for him. That someone in the Elysee was in the know and raised no objections would have been sufficient for the organisers to have gone ahead with their plan.

Oddly enough it is the now totally discredited Tricot report, drawn up at the government's request by the former de Gaulle aide Bernard Tricot a month ago, and ct-wring both the government and the secret service of involvement in the sinking of th. Rainbow Warrior, which provided a clue about who it was in the Elysee who might have been 'dans le parfum' as French secret service operators like to put it. That someone, according to M. Tricot, could only have been the President's chief milit- ary aide at the time — he is now chief of staff of the army — General Saulnier. For, again according to Tricot, it was General Saulnier who gave the green light for the funds to be deblocked for the operation, supposedly one of surveillance only according to Tricot's findings, funds amounting to close on half a million pounds. Could it have been possible for General Saulnier to have taken such a decision without reference if not to the President himself at least to his secretary- general? No answer to this all-important question has yet been made available. Yet if the President was kept in ignorance of the original plot, and one must assume that so also was M. Fabius, they learnt about its true nature very shortly after. The evi- dence for this is provided by the Minister of the Interior, M. Pierre Joxe — inciden- tally it is his ministry which has supplied Le Monde with most of its revelations — who told M. Mitterrand a week after the event that two French secret service agents had been arrested in New Zealand and that the scandal which would result from that would threaten M. Mitterrand himself. It was to protect the President from such an eventuality that he urged him to take swift action against those who had approved the scheme in the first place.

The President was unprepared to accept the urgency of such a move, which would have involved not only M. Hernu, an old friend of 30 years' standing, but also major military figures like General Saulnier, Admiral Lacoste and the then chief of staff General Lacaze. He decided to temporise in the hope that the Tricot report would silence the opposition and that the New Zealand police would not have sufficient evidence to link the arrested French couple directly with the sinking of the Rainbow Warrior; in short that the story that the French secret service was engaged in a purely surveillance operation would hold and the question of who actually sank the Rainbow Warrior would remain a mystery.

Meanwhile more and more information was flowing into both the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Justice regard- ing the scale of French involvement. To the Ministry of the Interior it came from the internal counter-espionage service which that ministry controls, and to the Ministry of Justice from those members of the police judiciaire who had been detailed to help the New Zealand detectives in Paris and New Caledonia with their investigations. From these two sources it became more and more likely that the New Zealand police not only had enough evidence to convict the so-called Turenge couple but to come up with some highly embarrassing revelations of their own. It was at this point that M. Joxe was joined by the Minister of Justice, M. Badinter, in warning the Presi- dent of the increasing dangers that lay ahead as the trial of the `Turenges' in Auckland approached, with preliminary court proceedings scheduled for 4 Novem- ber. M. Fabius, too, was becoming in- creasingly nervous, first as a result of the failure of the Tricot report to placate public opinion, and second at the obvious determination of M. Hernu to protect the military at all costs. He too began pressing for M. Hernu's resignation, asking M. Mitterrand to agree to it on at least three occasions in the past month and being refused each time.

At this moment M. Hernu was glorying in his role as protector of the honour of the French army and the praise that was being lavished on him in right-wing circles as 'a patriotic socialist'. On the fateful Tuesday when Le Monde came out with its revela- tions that a third team of French military frogmen apart from the two already pre- sent on the scene had actually carried out the bombing of the Rainbow Warrior, M. Hernu found nothing better to do than give a lunch for Mlle Christine Clerc, a reporter on the right-wing Figaro magazine to thank her for having written flatteringly of him. In the course of the lunch proofs of Le Monde's article were being rushed to him and after glancing at them he passed them to Mlle Clerc with the comment: 'It is obvious who is the real author of this piece — it's Joxe.'

Odd aspects of the operation remain intriguing mysteries. Why, for example, was the Zodiac rubber dinghy used in the attack on the Rainbow Warrior bought in London? Was it just a piece of secret service mystification, or was it done de- liberately to point the finger at Britain? Why was the yacht Ouvea with its crew of military divers scuttled in mid-South Paci- fic after leaving Auckland and after having successfully cleared customs at Norfolk Island?

There is finally the deeper mystery of why such vast means were brought to bear on a target which, while being a nuisance to French nuclear testers in their Pacific possessions, could in no way be considered a menace. In this matter the masterminds who plotted the sinking revealed them- selves not only as fools but as paranoid and vainglorious ones. As for the political implications, they do not have to be laboured. The chances of M. Mitterrand completing his presidential term, which ends in 1988, by being able to 'cohabit' with a right-wing parliamentary majority after the elections next March have been re- duced to almost zero. Even M. Fabius's immediate future must remain in doubt. He has already suffered the humiliation of having to go back on his promise that if French involvement in the affair were proved, then those who carried out this criminal act would be brought to trial in France. One can only speculate what furth- er humiliations are in store for him in the days and weeks to come.

Previous page

Previous page