ARTS

Architecture

The Prince's quest

Alan Powers sees hope for the common man at a summer school in Italy The vested interests of the architectural profession represent a tiny section of soci- ety. It defends an untenable viewpoint and so staves off real discussion. This is the view of Christopher Alexander, Professor of Architecture at the University of Berke- ley, California, who for the second year running was teaching on the Prince of Wales's Summer School in Civil Architec- ture. The accusation that the Prince of Wales is promoting only a return to roman- tic classicism is one that Alexander rejects. His own history, branching off from the orthodox modern movement towards a new vision of a building and place-making in the service of society and individuals, has gone far beyond questions of style to demand a reassessment of the way that architects act within the building process.

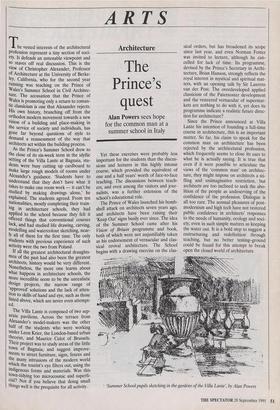

As the Prince's Summer School drew to the close of its six-week term in the idyllic setting of the Villa Lante at Bagnaia, stu- dents were busy cutting up cardboard to make large rough models of rooms under Alexander's guidance. 'Students have to understand that they don't have what it takes to make one room work — it can't be studied by making drawings alone,' he explained. The students agreed. From ten nationalities, mostly completing their train- ing in architecture schools, they had applied to the school because they felt it offered things that conventional courses lack, and had studied life drawing, carving, modelling and watercolour sketching, near- ly all of them for the first time. The only students with previous experience of such activity were the two from Poland.

If all the greatest architectural draughts- men of the past had also been the greatest architects, history would be very different. Nonetheless, the more one learns about what happens in architecture schools, the more incredible seem to be the unrealistic design projects, the narrow range of approved' solutions and the lack of atten- tion to skills of hand and eye, such as those listed above, which are never even attempt- ed.

The Villa Lante is composed of two sep- arate pavilions. Across the terrace from Alexander's model-makers was the other half of the students who were working under Leon 'Crier, the London-based urban theorist, and Maurice Culot of Brussels. Their project was to study areas of the little town of Bagnaia, and suggest improve- ments to street furniture, signs, fences and the many intrusions of the modern world which the tourist's eye filters out, using the indigenous forms and materials. Was this town-tidying too microcosmic and superfi- cial? Not if you believe that doing small things well is the prequisite for all activity. Yet these exercises were probably less important for the students than the discus- sions and lectures in this highly intense course, which provided the equivalent of one and a half years' worth of face-to-face teaching. The discussions between teach- ers, and even among the visitors and jour- nalists, was a further extension of the school's educational role.

The Prince of Wales launched his bomb- shell attack on architects seven years ago, and architects have been raising their `Keep Out' signs busily ever since. The idea of the Summer School came after his Vision of Britain programme and book, both of which were not unjustifiably taken as his endorsement of vernacular and clas- sical revival architecture. The School begins with a drawing exercise on the clas- sical orders, but has broadened its scope since last year, and even Norman Foster was invited to lecture, although he can- celled for lack of time. Its programme, devised by the Prince's Secretary in Archi- tecture, Brian Hanson, strongly reflects the royal interest in mystical and spiritual mat- ters, with an opening talk by Sir Laurens van der Post. The overdeveloped applied classicism of the Paternoster development and the veneered vernacular of supermar- kets are nothing to do with it, yet does its programme indicate a realistic future direc- tion for architecture?

Since the Prince announced at Villa Lante his intention of founding a full-time course in architecture, this is an important matter. So far, his claim to speak for the common man on architecture has been rejected by the architectural profession, which frequently seems to close its ears to what he is actually saying. It is true that even if it were possible to articulate the views of the 'common man' on architec- ture, they might impose on architects a sti- fling and unimaginative restriction, but architects are too inclined to seek the abo- lition of the people as undeserving of the confidence of the profession. Dialogue is all too rare. The sensual pleasures of post- modernism and high tech have not restored public confidence in architects' responses to the needs of humanity, ecology and soci- ety, even in such simple matters as keeping the water out. It is a bold step to suggest a restructuring and redefinition through teaching, but no better testing–ground could be found for this attempt to break open the closed world of architecture. Architecture courses first developed in Britain before 1914 as an alternative to pupilage, rejecting the regional pragmatism of the Arts and Crafts in favour of 'monu- mental classic' based on the American ver- sion of the French Beaux Arts tradition. This orthodoxy was in turn overthrown by the modern movement in the years before and after the war, but already by 1960 a few people in England and America recog- nised that modernism had become ossified into a self-perpetuating formula as restric- tive as the Beaux Arts method had been before.

These shifts have been understood his- torically as a succession of styles, and while the debate (more a case of separate mono- logues) of style continues, even in the easy abstention represented by pluralism, noth- ing is likely to change. The Prince's Sum- mer School is encouraging evidence that on his part the question will not be seen in stylistic terms alone, although the philo- sophical and spiritual grounding it presents is a ready target for cynics and needs to be supported by a rigorous and critical use of history and theory. Solutions from the past, whether they are forms like the classical orders or institutions like architectural pupilage, cannot be taken for granted or applied indiscriminately.

It was clear from the Prince's speech at Villa Lante that while his architectural campaign is set to continue, it has devel- oped from simple opposition to modern architecture towards becoming part of a broader-based international resistance net- work, related to global politics of housing and environment. This is likely to offer architects themselves a more fulfilling and rewarding role in serving humanity rather than designing speculative office blocks, quite apart from the possible benefits to building users.

'Thank God it's only on Sunday that the seeds of doubt are sown.'

Previous page

Previous page