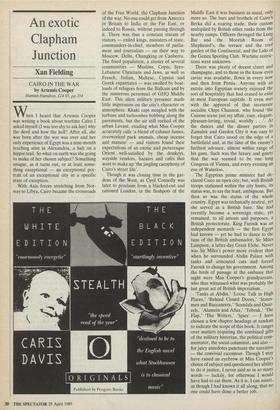

An exotic Clapham Junction

Xan Fielding

CAIRO IN THE WAR by Artemis Cooper Hamish Hamilton, £14.95, pp.354 hen I heard that Artemis Cooper was writing a book about wartime Cairo I asked myself (I was too shy to ask her) why the devil and how the hell? After all, she was born after the war was over and her only experience of Egypt was a nine-month teaching stint in Alexandria, a halt on a hippie trail. So what on earth was she going to make of her chosen subject? Something unique, as it turns out, or at least some- thing exceptional — an exceptional por- trait of an exceptional city in a specific state of exception.

With Axis forces stretching from Nor- way to Libya, Cairo became the crossroads of the Free World, the Clapham Junction of the war. No one could get from America or Britain to India or the Far East, or indeed to Russia, without passing through it. There was thus a constant stream of visitors — exiled kings, ministers, of state, commanders-in-chief, members of parlia- ment and journalists — on their way to Moscow, Delhi, Chungking or Canberra. The fixed population, a cluster of several communities — Muslims, Copts, Syro- Lebanese Christians and Jews, as well as French, Italian, Maltese, Cypriot and Greek expatriates — was swelled by boat- loads of refugees from the Balkans and by the numerous personnel of GHQ Middle East. This alien military presence made little impression on the city's character or atmosphere. Khaki caps mingled with the turbans and tarbooshes bobbing along the pavements, but the air still reeked of the urban Levant, exuding what Miss Cooper accurately calls 'a blend of exhaust fumes, overworked pack animals, cheap incense and manure' — and visitors found their expectations of an exotic and picturesque Orient well-satisfied by the donkeys, wayside vendors, bazaars and cafés that went to make up 'the jingling cacophony of Cairo's street life'.

Though it was closing time in the gar- dens of the West, as Cyril Connolly was later to proclaim from a blacked-out and rationed London, in the fleshpots of the Middle East it was business as usual, only more so. The bars and brothels of Cairo's Berka did a roaring trade, their custom multiplied by British other ranks from the nearby camps. Officers thronged the Long Bar and the Moorish Room of Shepheard's, the terrace and the roof garden of the Continental, and the Lido of the Gezira Sporting Club. Wartime restric- tions were unknown.

There was plenty of decent claret and champagne, and to those in the know even caviar was available, flown in every now and then from Persia. Anyone with an entrée into Egyptian society enjoyed the sort of hospitality that had ceased to exist in most European capitals. It even met with the approval of that inveterate socialite Chips Channon, who found 'the Cairene scene just my affair, easy, elegant, pleasure-loving, trivial, worldly . . At the dances and the dinner parties in Zamalek and Garden City it was easy to forget that Cairo stood on the edge of a battlefield and, at the time of the enemy's furthest advance, almost within range of his guns. Such was the luxury and gaietY that the war seemed to be one long Congress of Vienna, and every evening an eve of Waterloo.

The Egyptian prime minister had de- clared Cairo an open city; but;with British troops stationed within the city limits, its status was, to say the least, ambiguous. But then so was the status of the whole country. Egypt was technically neutral, yet she served as a British base. She had recently become a sovereign state, yet remained, to all intents and purposes, a British protectorate. King Farouk was an independent monarch — the first Egypt had known — yet he had to dance to the tune of the British ambassador, Sir Miles Lampson, a latter-day Great Elche. Never was Sir Miles's power more evident than when he surrounded Abdin Palace with tanks and armoured cars and forced Farouk to change his government. Among the birds of passage at the embassy that night were Miss Cooper's grandparents, who thus witnessed what was probably the last great act of British imperialism.

'Tanks at Abdin,"Loose Talk in High Places,' Behind Closed Doors,' States- men and Buccaneers,' Scandals and Quar- rels,' Alamein and After,' Tobruk,"The Flap,' The Writers,' Spies' — I have chosen a few chapter headings at random to indicate the scope of this book. It ranges over matters requiring the combined gifts of the military historian, the political com- mentator, the social columnist, and also — for juicy anecdotes punctuate the narrative — the convivial raconteur. Though I may have raised an eyebrow at Miss Cooper's choice of subject and questioned her ability to do it justice, I never said so in so many words — luckily, for otherwise I would have had to eat them. As it is, I can assert, as though I had known it all along, that no one could have done a better job.

Previous page

Previous page