`OUR DON QUIXOTE'

Hugh Trevor-Roper explains

the vast illusion which possessed Rudolf Hess

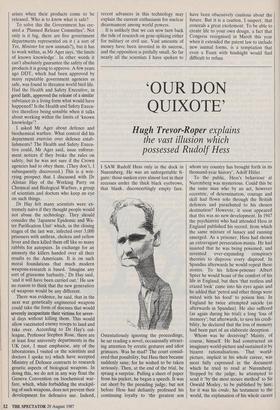

I SAW Rudolf Hess only in the dock in Nuremberg. He was an unforgettable fi- gure: those sunken eyes almost lost in their recesses under the thick black eyebrows, that blank, disconcertingly empty face.

Ostentatiously ignoring the proceedings, he sat reading a novel, occasionally attract- ing attention by erratic gestures and idiot grimaces. Was he mad? The court consid- ered that possibility, but Hess then became suddenly sane; for he wished to be taken seriously. Then, at the end of the trial, he sprang a surprise. Pulling a sheet of paper from his pocket, he began a speech. It was cut short by the presiding judge; but not before Hess had defiantly professed his continuing loyalty to 'the greatest son whom my country has brought forth in its thousand-year history', Adolf Hitler.

To the public, Hess's behaviour at Nuremberg was mysterious. Could this be the same man who by an act, however eccentric, of determination, courage and skill had flown solo through the British defences and parachuted to his chosen destination? However, it soon appeared that this was no new development. In 1947 the psychiatrist who had attended Hess in England published his record, from which the same mixture of lunacy and cunning emerged. As a prisoner, Hess had shown an extravagant persecution-mania. He had insisted that he was being poisoned, and invented ever-expanding conspiracy theories to disprove every disproof. In Spandau afterwards he would repeat these stories. To his fellow-prisoner Albert Speer he would boast of the comfort of his life in England, but then 'that restless and crazed look' came into his eyes again and he added that 'petrol and other things were mixed with his food' to poison him. In England he twice attempted suicide (as afterwards in Spandau). He also suffered (as again during his trial) a long 'loss of memory'; but afterwards, to save his credi- bility, he declared that the loss of memory had been part of an elaborate deception.

Whom was he deceiving? Mainly, of course, himself. He had constructed an imaginary world-picture and sustained it by bizarre rationalisations. That world- picture, implicit in his whole career, was most fully expressed in the document which he tried to read at Nuremberg. Stopped by the judge, he attempted to send it 'by the most secure method' to Sir Oswald Mosley, to be published by him; for it was his credo, his testament to the world, the explanation of his whole career and of the extraordinary adventure of 1941, so misunderstood by everyone, in- cluding his hero Hitler who had reacted by declaring him mad.

To Hess, the whole world was divided between the forces of good and evil. The Aryan races were good, the Jews evil. Unfortunately the noble but innocent Aryans were easily manipulated by the wicked but diabolically clever Jews, who, while remaining themselves 'in the back- ground', secretly hypnotised even the ablest of them and so made them behave stupidly, suicidally, to further their own plans of domination. This theory of hypno- sis became an essential element in Hess's philosophy. He alleged that he could al- ways detect it from the 'glazed' expression in the eyes of the victims.

Hess was one of those dependent souls who are born to believe and this primitive Nazi idealism governed and explained his whole life, at least from 1920 when he accepted Hitler as his infallible god. Hitler, he said publicly in June 1934, 'is always right and always will be right'. Only a few days later, when Hitler ordered the mas- sacre of the SA, Hess begged for the privilege of personally shooting its leader, Ernst Roehm. Seven years later, the same naive idealism drove him to his great miscalculated adventure: the flight to Scot- land.

For how was it, Hess asked himself, that two noble Aryan races, the British and the German, had become locked in a fratricid- al war? Hitler, as he knew, had never wanted war with Britain: he only wanted a free hand in the East. Clearly, the British leaders must have been bewitched by the Jews. But were they all bewitched? Was there not a sound core of honest men — the King perhaps, and the old aristocracy who could resist the spell? If only he could find a guide to that sound core, then perhaps the bewitched or corrupted pup- pets of the Jews could be pushed -aside, Aryan harmony restored, and the way opened for the Eastern crusade. That Hitler was already poised to launch that crusade, Hess probably did not know; but that was immaterial. He knew his master's mind. Moreover, he thought that he had found a guide to the sound core of Britain: the Duke of Hamilton.

Why Hamilton? Hess had never met him, knew nothing about him personally. It was a mysterious and, for the duke, an embarrassing choice. But the mystery was solved in 1971 when the duke's son, Lord James Douglas-Hamilton, published his book introducing the character of Albrecht Haushofer. Haushofer was the son of Professor Karl Haushofer, the 'geopoliti- cian' of Munich, Hess's revered teacher; as such he was protected by Hess, and he needed that protection, for his mother was Jewish. A cultivated cosmopolitan, he was friendly with the duke, and thought that, through him, a peace might be negotiated: a peace which, it seemed, might strengthen his patron's now weakened position and his own protection. But Haushofer's attempts to open correspondence with the duke were unsuccessful and the simple-minded Hess decided to take a short cut. His head full of illusions, his pockets stuffed with amulets, elixirs and nostrums, he piloted himself to Scotland and parachuted almost on the ducal estate.

The result was predictable. If Hess's departure caused dismay at Hitler's court, his arrival caused only embarrassment in Britain. The Russians, 'naturally, were suspicious, and their suspicions were in- creased by Churchill's reticence. Hess him- self, when he found himself treated as a prisoner of war, took refuge in his fanta- sies. The British officers who dealt with him might be courteous, but what of that glazed look in their eyes? So the familiar syndrome was set off. He took elaborate precautions over his food, sometimes sud- denly swapping plates with a surprised neighbour, and sent samples from the lavatory to the Swiss minister in London for analysis. When the minister found nothing sinister in the deposit, Hess con- cluded that he too had been bewitched, no doubt when lunching at his London club. When the war was finally lost, the number of bewitched had, of course, expanded greatly: the King of Italy and Marshal Badoglio for making peace, Count von Stauffenberg and his friends for trying to assassinate Hitler, the captive German

'It looks like we must be in the wilderness.'

generals who broadcast from Moscow, Goebbels, Himmler and Bormann for otherwise inexplicable tactical mistakes.

So, at Nuremberg, Hess played his last part in the cosmic drama of his imagina- tion. He refused to recognise the court because the whole trial, he insisted, was irrelevant. The real war-criminals, the Jews, who should have been in the dock, were still 'in the background'. But his evasions had their limits, for he was determined, at the end, to utter his credo. Even after the gates of Spandau had closed behind him, he remained constant in his ideas. In 1947 he surprised his fellow- prisoners by evident signs that he was `putting together a new government'. The old Nazis, released from Spandau, were to form, under him, a German government acceptable to the Western powers. His fellow-prisoners were not impressed. The most sympathetic of them, Speer, called Hess 'our Don Quixote'. Perhaps that should be his epitaph.

There are still mysteries about Hess's flight to Britain. The British Government has still not released the full facts. But it is unlikely that any new revelations will alter the portrait of the naive Nazi fundamental- ist who paid so heavy a price not for his crimes but for his illusions.

Previous page

Previous page