ARTS

Exhibitions

The Art of Drawing in France 1400-1900 (National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, till 19 October)

Architects' collections

Giles Auty

0 f all the things one might collect, good drawings and prints strike me as just about the most satisfying and sensible. With drawing especially, the collector gets artistry of a most rewarding kind some- times at relatively low cost. Best of all, flat sheets of paper take very little space to store.

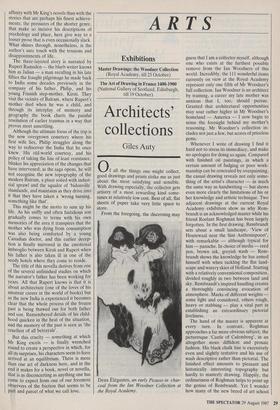

From the foregoing, the discerning may Deux Elegantes, an early Picasso in char- coal from the Ian Woodner Collection at the Royal Academy. guess that I am a collector myself, although one who exists at the furthest possible remove from the Ian Woodners of this world. Incredibly, the 111 wonderful items currently on view at the Royal Academy represent only one fifth of Mr Woodner's full collection. Ian Woodner is an architect by training, a career my late mother was anxious that I, too, should pursue. Granted that architectural opportunities may soar rather higher in Mr Woodner's homeland — America — I now begin to sense the foresight behind my mother's reasoning. Mr Woodner's collection in- cludes not just a few, but scores of priceless gems.

Whenever I write of drawing I find it hard not to stress its immediacy, and make no apologies for doing so again. Compared with finished oil paintings, in which a certain amount of fudging or poor work- manship can be concealed by overpainting, the casual drawing reveals not only some- thing of the artist's character — in much the same way as handwriting — but shows even more clearly the limitations of his or her knowledge and artistic technique. Two adjacent drawings at the current Royal Academy exhibition show us why Rem- brandt is an acknowledged master while his friend Roelant Roghman has been largely forgotten. In the first drawing, Rembrandt sets about a small landscape, 'View of Houtewaal near the Sint Anthonispoort', with remarkable — although typical for him — panache. In choice of media — reed pen, brown ink, greyish wash — Rem- brandt shows the knowledge he has armed himself with when tackling the flat land- scape and watery skies of Holland. Starting with a relatively conventional composition, divided roughly in two between land and sky, Rembrandt's inspired handling creates a thoroughly convincing evocation of atmosphere. Marks of different weights some light and considered, others rough, heavy or stabbing — play a vital part in establishing an extraordinary pictorial liveliness.

The hand of the master is apparent at every turn. In contrast, Roghman approaches a far more obvious subject, the picturesque 'Castle of Culemborg', in an altogether more diffident and prosaic fashion. His black chalk line is excessively even and slightly tentative and his use of wash descriptive rather than pictorial. The finished effect amounts to pleasant and historically interesting topography but hardly to masterly drawing. Happily, the ordinariness of Roghman helps to point up the genius of Rembrandt. Yet I wonder how many of the new breed of art school teachers, who scorn the continuing necessi- ty of drawing from the subject, would spot this kind of difference?

Those keenest on change and innovation in education are also often the most blind to the lessons still to be learned from past achievements. Probably the greatest con- ceit of each age lies in a widespread belief in its own unique importance. Often this leads to a damaging eagerness to scrap the time-proven. Exhibitions of master draw- ings are salutary, not least in showing us that in certain areas of direct competition we cannot compete confidently with our forebears. Who can draw today with the certainty of Holbein or Darer or the dash of Tiepolo? The widely voiced notion that such skills are no longer 'relevant' in our blessed era of the computer and car tele- phone is simply an attempt to save face. Far from being outmoded, great drawing from the past often has the effect, for me, of shrinking the years that have passed since the artist's hand passed over the paper. What is it that is held to have happened in the 400-odd years since Cellini drew his wonderful 'Satyr' or since Parmi- gianino formed his exquisite 'Madonna and Child' which makes either, in any true sense, irrelevant?

To those who love such things a great drawing is, in itself, a marvel, at least comparable in achievement with master- pieces of statesmanship or scientific discov- ery. That a tiny piece of paper covered with a few marks can carry a huge charge of feeling seems almost miraculous. Yet stop in front of, say, Goya's 'Loco furioso' (`Raging lunatic') at the Academy and I am confident you will share my feelings. The Royal Academy exhibition includes works from six major national schools and spans roughly 500 years. Lovers of the paintings of Seurat will enjoy especially his four contd drawings.

Seurat does not feature in the exhibition of French Master drawings from Stock- holm at the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, although most other French 19th-century masters are included among the 145 items on view, the earliest of which dates from the start of the 15th century. A lovely portrait by Quesnel, believed to be of Christine of Lorraine, is matched by one from Claude Mellan made three quarters of a century later. This is of Henrietta Anne of England, whose mother fled the Civil War here in 1644.

Other drawings of great personal in- terest include an object lesson in the rendering of foliage by Pierre-Jean Mariet- te and works by Fragonard, Ingres, Corot and Rodin. The collection is based on those of Nicodemus Tessin the younger, an 18th-century architect, and of his son, Carl Gustav Tessin, who was obliged, by finan- cial straits, to sell out to the King of Sweden in 1755. Royalty, one imagines, seldom suffers from cash-flow crises. Perhaps it is even better to be a king than an architect.

Previous page

Previous page