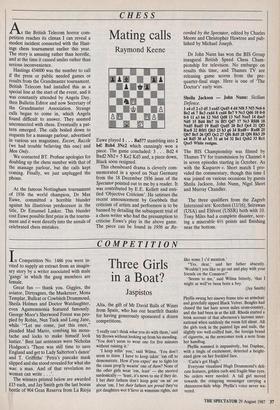

COMPETITION

Three Girls in a Boat?

Jaspistos

In Competition No. 1486 you were in- vited to supply an extract from an imagin- ary story by a writer associated with male `gangs' in which the gang members are female.

Great fun — thank you. Giggles, the aviator, Dirtyagnes, the Musketeer, Mona Templar, Bullcat or Cowbitch Drummond, Sheila Holmes and Doctor Watdaughter, even Agamemnonia featured famously. George Moor's Sherwood Forest was peo- pled by Robin, Nun Tuck and. Long Jane, while "'Let me come, just this once," pleaded Mad Mario, combing his mous- tache and locks to make himself look lustier.' Best last sentences were Nicholas Hodgson's 'There was still time to save England and get to Lady Salterton's dance' and T. Griffiths' Petra's pancake mask slipped and she stood revealed for what she was: a man. And of that revelation no woman can write . . .5.

The winners printed below are awarded £15 each, and Jay Smith gets the last bonus bottle of 904 Gran Reserva from La Rioja Alta, the gift of Mr David Balls of Wines from Spain, who has our heartfelt thanks for having generously sponsored a dozen competitions.

'I really can't think what you do with them,' said Mr Brown without looking up from his mending. 'You don't seem to wear one for five minutes without ruining it.'

`I keep tellin' you,' said Wilma. 'You don't seem to listen. I have to keep takin"em off to demonstrate. How d'you expec' me to fight- for the cause prop'ly wearin' one of them? None of the other girls wear 'em, least' — she snorted sardonically — 'least, it's news to me if they do. I bet their fathers don't keep goin' on an' on about 'em, I bet their fathers are proud they've got daughters wot b'lieve in wimmins rights, not

like some I c'd mention.'

"Yes, dear,' said her father absently. `Wouldn't you like to go out and play with your friends on the Common?'

`Seems to me,' said Wilma bitterly, 'that I might as weil've been born a boy.'

(Jay Smith) Phyllis swung her sinewy frame into an armchair and gratefully sipped Black Velvet. Beagles had chased the last hare seven miles cross-country, and she had been in at the kill. Rhoda started a brisk account of that afternoon's lacrosse inter- national when suddenly the room fell silent. All the girls took in the painted lips and nails, the slightly too well-coiffed hair, the foreign brand of cigarette, as the newcomer took a note from her handbag.

Phyllis scanned it impassively, but Daphne, with a tingle of excitement, detected a height- ened glow on her freckled face.

`Carla's got Hugh.'

Everyone visualised Hugh Drummond's deli- cate features, golden curls and fragile blue eyes.

No orders were needed. A tall girl moved towards the cringeing messenger carrying a rhinoceros-hide whip. Phyllis's voice never wa- vered. 'He gets ten strokes only, morning and evening. Fifteen on Sundays. Vaseline after- wards. Now everybody — Biarritz!'

(Martin Williams) It had been a hard night of lambing, but the Cotswold ewes seemed well content to suckle their black-avised Border progeny. In the Com- munal House below, there were women staying up late over embroidery and ripe talk. I won- dered at my sudden discontent and rejected it as sickly.

Phemie Banff helped me off with my gaiters. Still stiff-jointed, I allowed her to usher me into the Commune Room. Maureen was there, of course: she was an adept at cajoling 'nights off' from every kind of Chiswick publican. Hilary Braxter, famous for managing a half-score of Wiltshire launderettes, held her hand fiercely. But it was Froufrou van den Hout, resplendent in diamante spectacles, who forced us all to the grim business of that fateful sunrise.

`Tessa, honey,' she drawled, 'looks like the Old Woman is staking herself a claim in your Anthrax proposition.'

(Roger Jeffreys) `Someone will have to go into the river,' said Alice, directing a meaning look at Dinah. Just so did Dinah look at me, and I look at Alice, until the air was fuller than it could bear of signifi- cance.

'All right,' I said. 'You keep a look-out while I take my clothes off.' It was only fair, I had been responsible for the loose painter that had tangled with the rudder. Happily it only took a minute or two in the cold water for me to free the rope, but it was Montmorency and not the look-out that made us aware of the visitors. Montmorency was frolicking round three clerkish-looking men on the bank. 'That,' said Alice, 'is the sort of danger your mother said he'd protect us from,' and went on, raising her voice, 'Would you gentlemen please turn your backs so that my friend can get out of the river?'

There followed a short, foot-shuffling pause and the taller of the three replied, 'We're not gentlemen, Miss.'

(John Sweetman) They surveyed the pile of branches.

`Come on, Chaffinch Patrol,' cried Jane. 'Remember what Captain said about coping with emergencies. Betty, you collect poles; Mary, you go wooding; and Phyllis, get Water from that stream.'

'What about me?' moaned Tracy. 'I don't belong to your silly old guides.'

'Captain said . . .', began Jane.

'Stuff your captain,' shouted Tracy. 'You think you know everything. I'm going to find some boys; they'll make shelters for us.'

'Stupid', muttered Betty from a Birnam Wood of foliage. 'There weren't any boys on the plane.'

'But there was the pilot,' retorted Tracy; 'he was ever so nice.'

'Oh, leave her alone,' said Jane. 'Sylvia, what are you doing picking those flowers?'

'I wanted to make the shelter look pretty,' began Sylvia.

'First things first,' replied Jane. 'Get to work, everybody.'

'I hate you,' sobbed Tracy, going off towards the sea. 'I'll tell my mum about you.' (0. Smith)

Previous page

Previous page