Exhibitions

Allan Ramsay (Scottish National Portrait Gallery, till 27 September) James Pryde (Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, till 11 October) 150th Anniversary Exhibition (The Scottish Gallery, till 9 September)

Pryde of Scotland

Allan Massie

t is Scottish year at Edinburgh where

the visual arts are concerned. Though the Royal Scottish Academy is housing a splen- did exhibition of Miro sculptures, and Though the main exhibition at the National Gallery is Dutch Art in Scotland, the two most interesting of the official Festival exhibitions are retrospectives of Scottish painters: Allan Ramsay and James Pryde.

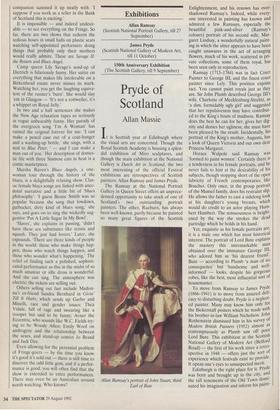

The Ramsay at the National Portrait Gallery in Queen Street offers an unprece- dented opportunity to take stock of one of Scotland's two outstanding portrait painters. The other, Raeburn, has always been well-known, partly because he painted so many great figures of the Scottish Allan Ramsay's portrait of John Stuart, third Earl of Bute Enlightenment, and his renown has over- shadowed Ramsay's. Indeed, while every- one interested in painting has known and admired a few Ramsays, especially the beautiful pink-and-silver (Ramsay's colours) portrait of his second wife, Mar- garet Lindsay, a wonderfully natural paint- ing in which the sitter appears to have been caught unawares in the act of arranging flowers, much of his work, scattered in pri- vate collections, some of them royal, has been seen only in reproduction.

Ramsay (1713-1784) was in fact Court Painter to George HI, and the finest court painter since Lely. This position enjoins tact. You cannot paint royals just as they are. Sir John Plumb described George III's wife, Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, as 'a dim, formidably ugly girl' and suggested that her repulsiveness may have contribut- ed to the King's bouts of madness. Ramsay does the best he can for her, gives her dig- nity and denies her ugliness; she must have been pleased by the result. Incidentally, his portrait of the King's mother, Augusta, has a look of Queen Victoria and our own dear Princess Margaret. Horace Walpole said Ramsay was 'formed to paint women'. Certainly there is a tenderness in his female portraits, and he never fails to hint at the desirability of his subjects, though stopping short of the open lubricity of French contemporaries like Boucher. Only once, in the group portrait of the Mansel family, does his restraint slip. He allows the father to cast a sidelong look at his daughter's young breasts, which would do credit to an actor playing Hum- bert Humbert. The sensuousness is height- ened by the way she strokes the dead partridge which he holds in his hand. Yet, exquisite as his female portraits are, it is a male one which has most historical interest. The portrait of Lord Bute explains the mastery this unremarkable man obtained over the immature George III, who adored him as 'his dearest friend'. Bute — according to Plumb 'a man of no consequence' but 'handsome and well- informed' — looks, despite his gorgeous robes, like the best, most influential sort of housemaster.

To move from Ramsay to James Pryde (1866-1941) is to move from assured deli- cacy to disturbing doubt. Pryde is a neglect- ed painter. Many may know him only for the Bickerstaff posters which he made with his brother-in-law William Nicholson. John Rothenstein dismissed him in his survey of Modern British Painters (1952) almost as contemptuously as Plumb saw off poor Lord Bute. This exhibition at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (Belford Road) — the first of his work since a retro- spective in 1948 — offers just the sort of experience which festivals exist to provide. It opens one's eyes to unsuspected merit. Edinburgh is the right place for it. Pryde was born and brought up in the city, and the tall tenements of the Old Town domi- nated his imagination and inform his paint-

ings. Bohemian by nature, devoted to the theatre and brandy-and-soda, a frequenter of the Café Royal, of the National Sporting Club and the Adelphi Hotel, a friend of John and Orpen, Phil May and Sickert, Pryde produced art that is macabre, dis- concerting, discordant. After his early years, when he worked in the theatre and depicted actors (and criminals), he rarely drew from life, something Rothenstein held against him. Pryde's works proceeded from imagination, memory and long brood- ing. He may be called a conceptual painter, and perhaps the most adverse criticism which may be offered is that he seems to have been more interested in the idea he was conveying than in the means employed.

Yet his paintings will stick in the memory and work in it. Some have seen the influ- ence of Velazquez, and. no doubt it is there; but the two artists he calls most forcibly to mind are Piranesi and de Chiri- co. Works like 'The Deserted Garden', `The Blue Ruin' and 'The Shrine' have all the disturbing quality of di Chirico or of an M.R. James ghost story. 'The Slum' and the series called The Human Comedy, which features a ragged four-poster bed, are powerfully gloomy: strange works to have emerged from the world of the Café Royal and the Oyster Bars of the Strand and Brighton. Pryde was a heavy drinker who died in a charity ward: his paintings convey the sense of waste inherent in dissi- pation, the melancholy that lurks behind the Edwardian swagger.

His chief patron was Lady Cowdray, and 17 of these works come from the collection at Dunecht House. The Cowdrays were given to success and philanthropy. How odd then that Lady Cowdray should have settled on this artist, and how perceptive of her! Pryde was a friend also of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, and there is a stylistic resemblance between his paintings and Mackintosh's masterpiece, the Glasgow School of Art. Mackintosh's reputation has never stood higher; Pryde's should now ascend to a comparable height. Like Mack- intosh, he was at least 'a nearly-great'.

One other exhibition should be men- tioned. The dealers Aitken Dott (The Scot- tish Gallery, George Street) are celebrating their 150th anniversary with a retrospective of their history. This runs from Orchardson and Robert Dick Lauder (Pryde's great- uncle) to Alison Watt and John Byrne. It is both an education and a delight. Covetable paintings are too numerous to list, but there are four Peploes, a J.D. Fergusson, a MacTaggart, a charcoal drawing of an Ital- ian priest (looking like Guinness as Fagin) by Robert Colquhoun, an admirable James Cummings and a gorgeous view of 'The Tweed at Makerstoun' by Earl Haig. Best of all is a Joseph Crawhall, 'American Jockeys', in the Degas or Guys class. Unfortunately it is priced at £95,000 — less than a Degas, I agree, but . . . but . . . alas.

Giles Auty is away.

Previous page

Previous page