Indian art

Monument to love

Juliet Reynolds

Recurring like a leitmotiv throughout Indian monumental art is an image that reflects the important place of sensuality in the ethos of the Indian people. This is the unified image of the male and female fig- ure which may be traced back, at least on a conceptual level, to a still widely venerated prehistoric fertility symbol, the yoni-lingam. In ancient monuments, the couple is gener- ally categorised as the mithuna, a term most aptly translated as 'lovers', though as an image its eroticism is largely implicit. It is not in sexual union that the lovers are portrayed, but in various relaxed postures that sometimes communicate playful dal- liance and sometimes sublime equanimity, while the overall expression is always one of tenderness and harmony.

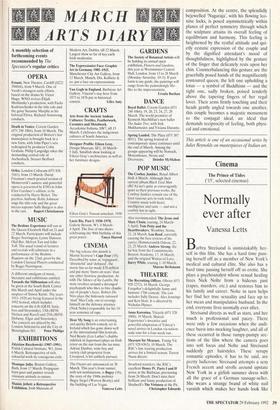

Inscriptions on early Buddhist monu- ments often identify the mithuna as a donor couple, in many cases a merchant and his consort. In later Buddhist monu- ments, as well as in the early great Hindu A tender expression of the conjugal ideal: the Naga King and Queen at Ajanta temples, the couple most often appears in the form of celestial and demi-divine beings, modelled on the ideals of the ruling aristocracy. It was only around the begin- ning of the mediaeval period in the 8th century that explicit eroticism began to find expression. The mithuna was gradually dis- placed by the maithuna (literally, coitus), an image that was to culminate in the baroque splendour of the vast erotic tem- ple sites of the 10th to 13th centuries where it appeared in a staggering variety of virtu- ally impossible poses. Strangely, perhaps, it is not in this exotically erotic form that the couple attains its greatest peak of artistry. For this we must return to the mithuna of the classical age which flowered in different regions between the 5th and 7th centuries and which, like the Renaissance, was an age of science and reason that abounded in guilds and workshops supported by discern- ing patrons. Yet what contrast between the chaste and painful icons of Christian Europe and the powerfully sensuous sacred art of India where, in the place of virgins and martyrs, masters built monumental icons to blissful lovers!

One of the most masterly of all such icons is a life-sized sculpture, identified as 'Naga King and Queen', carved in the late 5th century on the flank of a cave sanctuary at Ajanta (north-east of Bombay), one of the most important Buddhist sites in Asia. The royal couple and their female atten- dant are each protected by a cobra-halo, emblem of the half-human, half-serpent Naga, popularly believed to inhabit the underworld and protect the earth's riches, and consequently venerated by cultivators. But the word `naga' was also a generic word for a tribesperson who, although liv- ing largely on the fruits of the forest, belonged to a well-organised society far more equitable than the cultivator's. As the son of the elected king of a tribal republic, the Buddha had called upon his followers to offer special protection to all tribal peo- ples, so that `naga' became synonymous with 'noble of character' in Buddhist tradi- tion. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that this faith enjoyed the widespread support of local princes who ruled according to the democratic tribal model.

It is almost certain that the 'Naga' trio which occupies so prominent a place at Ajanta is a portrait of just such a ruler with his consort and lady-in-waiting. While many of its exquisite details have fallen prey to time and the elements, one can still discern the three distinct hair-types and features, evidence that, despite their highly idealised treatment, the figures are mod- elled on real people. The classical rules that governed such idealised naturalism demanded absolute mathematical precision in the proportioning and posturing of fig- ures. Though not immediately apparent, the entire composition, from its 'frame' inwards, consists of multiple geometrical elements which, if traced out, would appear as an absorbing Constructionist composition, At the centre, the splendidly bejewelled `Nagaraja', with his flowing leo- nine locks, is posed asymmetrically within planes of perfect symmetry through which the sculpture attains its overall feeling of equilibrium and harmony. This feeling is heightened by the restful attitude and qui- etly ecstatic expression of the couple and by the dignified attendant's mood of thoughtfulness, highlighted by the gesture of the finger that delicately rests upon her chin. Counterbalancing this gesture are the gracefully posed hands of the magnificently contoured queen, the left one upholding a lotus — a symbol of Buddhism — and the right one, sadly broken, poised tenderly above the tapering fingers of her regal lover. Their arms firmly touching and their heads gently angled towards one another, this couple becomes a majestic monument to the conjugal ideal, an ideal that demands reciprocity of feeling, both physi- cal and emotional.

This article is one of an occasional series by Juliet Reynolds on masterpieces of Indian art.

Previous page

Previous page