Architecture

Modern Architecture Restored (Building Centre, till 7 March)

The concrete crumbles

Alan Powers

It is odd how many of the owners of flat- roofed white-box houses of the 1930s seem to hate them. One might think that there are enough ordinary houses around. Yet for some people such buildings are tokens of a Poirot never-never land, while for

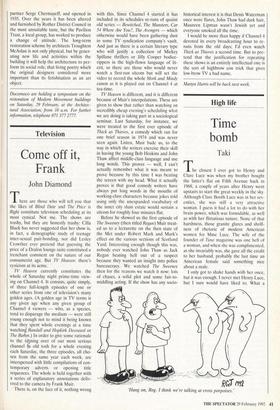

The staircase of the De la Warr Pavilion at Bexhill-on-Sea, now being restored architects of a certain bent they are talis- mans of truth in a time of darkness.

Never very numerous and often expen- sive to keep smart, early Modern Move- ment buildings continue to fascinate. In the 1970s, when modern architecture was a smug monopoly in need of severe external criticism, their fate in the hands of ordinary people was evidence of modernism's fail- ure. A book was published drawing this inescapable conclusion from the way that residents in a Modern Movement classic, Le Corbusier's housing estate at Pessac near Bordeaux (1928), had customised their machines for living in with thatched roofs and other clip-ons.

Horror among earnest architects, who had been nourished on the 1920s black and white photographs in the master's Oeuvre Complete. Today, with Pessac restored but Modernism in disarray, the situation is reversed, yet buildings in this country, par- ticularly post-war examples like Atexander Fleming House at Elephant and Castle, are in danger of demolition before time has allowed the praises of a specialised few to influence the many.

This exhibition at the Building Centre (26 Store Street, WC1) shows photographs of restoration schemes in Britain and Europe, exclusively of buildings which con- form to the strict canons of the Modern Movement, dating mostly from before the war. To document and conserve such build- ings is the aim of Docomomo, an organisa- tion founded in Holland in 1989 with branches in different countries. The exhibi- tion is the first public manifestation of the UK branch.

One point that it fails to make is that in Britain a greater number of buildings, including those of the Modern Movement and post-war period, enjoy protection from demolition or alteration through listing than in other countries, but we are also the most stingy in offering state funds for actu- al repair. Holland, for example, can show extraordinary examples of publicly funded restoration, including a housing estate in Rotterdam by J.J.P. Oud which is still in danger of sinking into its soft soil even after expensive repairs, and where part has now been rebuilt in replica.

Practical techniques for halting the effects of carbonation in concrete, which rusts reinforcement bars from within, have been successfully developed but the faithful restorer must revert to craft techniques to recapture the machine-age look. The idea of preserving the Modern Movement is riven with such contradictions. Polemics for and against modernism have made objec- tive judgment almost impossible, although since 1979 the Thirties Society, covering all buildings in Britain after 1914, not only those of the 1930s, has presented a bal- anced view and has helped the public and professionals to see quality regardless of style, saving many buildings in the process.

In the exhibition brochure, Dennis Sharp suggests that today's attitude to the Mod- ern Movement is 'rather like taking in an admired elderly relative and not, as some critics might suggest,a bizarre crazy cousin who stepped out of line and took a kick at conventional design attitudes'. Yet it is just this slightly patronising approach which the best Modern Movement buildings seem intent on resisting. They were mostly crazy in a deceptively rational way and often beautiful, contradicting their own mani- festos but full of poetry. No sensitive per- son wants to see them disfigured, but we might not feel comfortable borrowing their clothes.

Perhaps the most inspiring British restoration project is the De la Warr Pavil- ion at Bexhill-on-Sea, designed by the emi- gre German architect Erich Mendelsohn and his Russian-born, Harrow-educated partner Serge Chermayeff, and opened in 1935. Over the years it has been altered and furnished by Rother District Council in the most unsuitable taste, but the Pavilion Trust, a local group, has worked to produce a change of attitude. The long-term restoration scheme by architects Troughton McAsian is not only physical, but by gener- ating new life and activities within the building it will help the architecture to per- form its social role, that living poetry which the original designers considered more important than its fetishisation as an art object.

Previous page

Previous page