Stately home blues

Olivia Glazebrook

THE BIG HOUSE by Helena McEwen Bloomsbury, £12.99, pp. 186 Considering that the experience of some sort of childhood is common to every writer on the planet, it is odd that a con- vincing child's perspective is such a rare achievement in a novel. But it's not so hard to know that describing a view from the knees down, and calling it childhood, is an insult to any six-year-old.

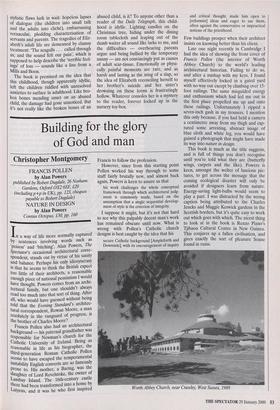

The Big House is about a little girl, Eliza- beth, who lives in a whopping stately home (complete with chapel and ha-ha) with a lovely family and fleets of servants. She eats jammy dodgers for tea, plays soldiers with her brother in the woods, and occasionally gets a smack from Nanny. Mama ignores her, which is horrid, and Papa gets squiffy if he can't pay the bills. When, in their twenties, two of Elizabeth's siblings die, Elizabeth goes back to the house and remembers them.

Reading The Big House is rather like lis- tening to someone describe a dream. The lack of structure, pace or progression is just as wearing, and despite a beautifully evoked relationship between Elizabeth and her brother James the style is that of 'What I Did in the Holidays' commissioned by Harpers & Queen. Each page exhibits a deadening 'technique — 'I look . . . I look back . . . I begin . . . I begin . . . I run . . . I go . . . and sit . . . I blink' — that reduces the terror and thrill of being a younger sis- ter to trundling about like a toy dog on wheels. However gripping the episode, Stylistic flaws lurk in wait: hopeless lapses of dialogue (the children into small talk and the adults into cliché), embarrassing vernacular, plodding characterisation of servants and parents. The tragedies of Eliz- abeth's adult life are demeaned by clumsy treatment: 'The seagulls. . . called through us, and the sound felt our pain', which is supposed to help describe the 'terrible feel- ings' of loss — sounds like a line from a Mills and Boon.

The book is premised on the idea that this childhood, though apparently idyllic, left the children riddled with unresolved anxieties to surface in adulthood. Like bro- ken bones mending unset on an abused Child, the damage had gone unnoticed. But it's not really like the broken bones of an abused child, is it? To anyone other than a reader of the Daily Telegraph, this child- hood is idyllic. Lighting candles on the Christmas tree, hiding under the dining room tablecloth and leaping out of the dumb waiter all sound like larks to me, and the difficulties — overhearing parents argue and being bullied by the temporary nanny — are not convincingly put as causes of adult scar-tissue. Emotionally or physi- cally painful moments are rare, and as harsh and lasting as the sting of a slap, so the idea of Elizabeth reconciling herself to her brother's suicide and her sister's drowning on these terms is frustratingly hollow. Whatever consoles her is a mystery to the reader, forever locked up in the nursery toy-box.

Previous page

Previous page