Building for the glory of God and man

Christopher Montgomery

FRANCIS POLLEN by Alan Powers published by Robert Dugdale, 26 Norham Gardens, Oxford 0X2 6SF, .£20 (including p+p in UK), pp. 123, cheques payable to Robert Dugdale) NATURE IN DESIGN by Alan Powers Conran Octopus, BO, pp. 160 In a way of life more normally captured by sentences involving words such as 'poison' and 'bitching', Alan Powers, The Spectator's occasional architectural corre- spondent, stands out by virtue of his sanity and balance. Perhaps his only idiosyncrasy is that he seems to think the British expect too little of their architects, a reasonable enough piece of national pessimism I would have thought. Powers comes from an archi- tectural family, but one shouldn't always read too much into that sort of thing. After all, who would have guessed without being told that the Evening Standard's architec- tural correspondent, Rowan Moore, a man resolutely in the vanguard of progress, is the brother of Charles Moore? Francis Pollen also had an architectural background — his paternal grandfather was responsible for Newman's church for the Catholic University of Ireland. Being as reasonable in life as his biographer, the third-generation Roman Catholic Pollen seems to have escaped the temperamental instability English converts are so famously Prone to. His mother, a Baring, was the daughter of Lord Revelstoke, the owner of Lambay Island. The 16th-century castle there had been transformed into a home by Lutyens, and it was he who first inspired Francis to follow the profession.

However, since from this starting point Pollen worked his way through to some stuff fairly brutally new, and almost back again, Powers is keen to assure us that his work challenges the whole conceptual framework through which architectural judg- ment is commonly made, based on the assumption that a single sequential develop- ment of style is the criterion of integrity.

I suppose it might, but it's not that hard to see why this palpably decent man's work has remained obscure until now. What is wrong with Pollen's Catholic church designs is best caught by the idea that his

secure Catholic background [Ampleforth and Downside], with its encouragement of inquiry and critical thought, made him open to [reformist] ideas and eager to use them, often against the conservative or impractical notions of the priesthood.

Few buildings prosper when their architect insists on knowing better than his client.

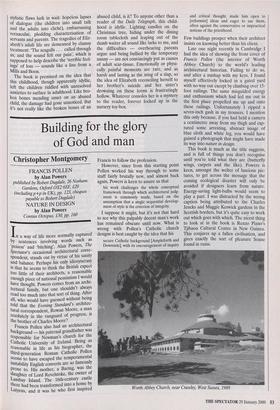

Late one night recently in Cambridge I had the idea of showing the front cover of Francis Pollen (the interior of Worth Abbey Church) to the world's leading architectural historian. Failing to do so, and after a mishap with my keys, I found myself effectively locked in a gated yard with no way out except by climbing over 15- foot railings. The same misguided energy and enthusiasm which had led me out in the first place propelled me up and onto these railings. Unfortunately I ripped a seven-inch gash in my trousers. I mention this only because, if you had held a camera a centimetre away from my thigh and cap- tured some arresting, abstract image of blue cloth and white leg, you would have gained a photograph that might have made its way into nature in design.

This book is much as the title suggests, and is full of things you don't recognise until you're told what they are (butterfly wings, carpets and the like). Powers is keen, amongst the welter of luscious pic- tures, to get across the message that the coming ecological disaster will only be avoided if designers learn from nature. Energy-saving light-bulbs would seem to play a part. I was distracted by the wrong caption being attributed to the Charles Jencks and Maggie Keswick gardens in the Scottish borders, but it's quite easy to work out which goes with which. The nicest thing to look at in the book is Renzo Piano's Tjibaou Cultural Centre in New Guinea. This conjures up a fallen civilisation, and gives exactly the sort of pleasure Soane found in ruins.

Worth Abbey Church, near Crawley, West Sussex, 1989

Previous page

Previous page