Exhibitions

Zoran Music

(Estorick Collection, 39a Canonbury Square, N1, till 17 September)

A life of wandering

Andrew Lambirth

Zoran Music is one of the great undis- closed secrets of 20th-century art. Born in 1909 in Gorizia, Dalmatia, near to what is now the Italian/Slovenian border, he grew up in the vanished world of Mitteleuropa in the last days of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Evacuated to Austria at the out- break of the first world war (an event he clearly remembers), Music began a lifetime of wandering which took him through Vienna and Prague to the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb (1930), and to Madrid and Toledo in 1935-36. With the coming of civil war to Spain, Music returned to his native Dalmatia, only moving to Venice in 1943. There he was arrested by the Gestapo for his association with Resistance members, tortured and sent to Dachau.

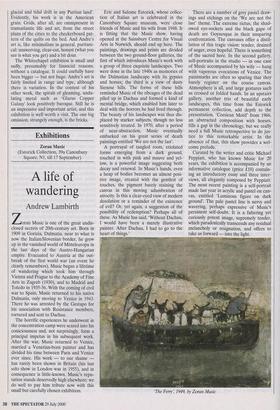

The horrific experiences he underwent in the concentration camp were seared into his consciousness and, not surprisingly, form a principal impetus in his subsequent work. After the war, Music returned to Venice, married a Venetian-born painter and has divided his time between Paris and Venice ever since. His work — to our shame has rarely been shown in Britain (his last solo show in London was in 1955), and in consequence is little-known. Music's repu- tation stands deservedly high elsewhere: we do well to pay him tribute now with this small but carefully chosen exhibition. Eric and Salome Estorick, whose collec- tion of Italian art is celebrated in the Canonbury Square museum, were close friends of Music and his wife from 1948. It is fitting that the Music show, having opened at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich, should end up here. The paintings, drawings and prints are divided between the two ground-floor galleries, the first of which introduces Music's work with a group of three exquisite landscapes. Two were done in the late 1940s as memories of the Dalmatian landscape with its gypsies and horses; the third is a view of dusty Sienese hills. The forms of these hills reminded Music of the ribcages of the dead piled up in Dachau and formed a kind of mental bridge, which enabled him later to deal with the horrors he had lived through. The beauty of his landscapes was thus dis- placed by starker subjects, though no less sensitively treated. In 1970, after a period of near-abstraction, Music eventually embarked on his great series of death paintings entitled 'We are not the last'.

A portrayal of tangled roots, etiolated forms emerging from a dark ground, touched in with pink and mauve and yel- low, is a powerful image suggesting both decay and renewal. In Music's hands, even a heap of bodies becomes an almost posi- tive image, created with the gentlest of touches, the pigment barely staining the canvas in this moving adumbration of atrocity. Is this a clear-eyed view of modern desolation or a reminder of the existence of evil? Or, yet again, a suggestion of the possibility of redemption? Perhaps all of these. As Music has said, 'Without Dachau, I would have been a merely illustrative painter. After Dachau, I had to go to the heart of things.' There are a number of grey pastel draw- ings and etchings on the 'We are not the last' theme. The extreme rictus, the shad- owed eye-sockets and the black gape of death are Goyaesque in their unsparing confrontation. The canvases offer a distil- lation of this tragic vision: tender, drained of anger, even hopeful. There is something of the sacred here. In the second gallery, self-portraits in the studio — in one case of Music accompanied by his wife — hang with vaporous evocations of Venice. The paintmarks are often so sparing that they barely register on the coarse canvas. Atmosphere is all, and large gestures such as crossed or folded hands. In an upstairs gallery, another trio of beautiful early landscapes, this time from the Estorick permanent collection, add depth to the presentation. 'Corsican Motif from 1966, an abstracted composition with horses, fills a gap in the chronology, but we really need a full Music retrospective to do jus- tice to this remarkable artist. In the absence of that, this show provides a wel- come prelude.

Curated by the writer and critic Michael Peppiatt, who has known Music for 20 years, the exhibition is accompanied by an informative catalogue (price £10) contain- ing an introductory essay and three inter- views, all elegantly composed by Peppiatt. The most recent painting is a self-portrait made last year in acrylic and pastel on can- vas, entitled 'Luminous figure on dark ground'. The pale pastel line is nervy and wavering, perhaps expressive of Music's persistent self-doubt. It is a faltering yet curiously potent image, supremely tender, which paradoxically transcends any residual melancholy or resignation, and offers to take us forward — into the light.

The Feny, 1949, by Zoran Music

Previous page

Previous page