NOT THE COMMON HURD

the summit season with more influence than any modern Foreign Secretary

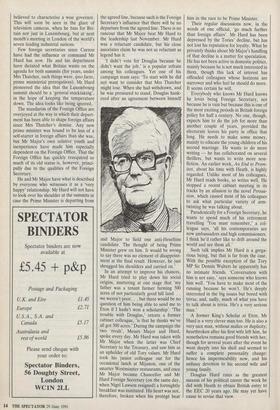

AS BRITAIN prepares for possible ambush by her European partners in Lux- embourg this weekend, she at least has the consolation of knowing that the Crown's most able minister will be in the team defending her. His friends and detractors (he seems not to have enemies) agree that Mr Douglas Hurd, Foreign Secretary since 1989, is probably the only serving minister who would have been invited to join any Tory cabinet since the war. He is certainly the only indispensable member of the present one. Modest, spectacularly compe- tent and a natural leader, he looks and sounds like Tory cabinet ministers are supposed to look and sound; in his dislike of confrontation and apparent absence of ideological commitment (qualities invalu- able for the days ahead), he could have come straight from the emollient Macmil- lian ministries of the late 1950s. Mr Hurd is assumed, given his close relationship with Edward Heath (whose private secretary he was from 1968 to 1974) and his attempts to tone down Mrs Thatch- er, to be an ardent European. However, he is not, as one might expect of a man who did 14 years in the Diplomatic Service, an ardent anything. His friends say he was upset by Jacques Delors' attempts to bounce Britain into accepting a federal principle for Europe; he instinctively radi- ates the traditional Foreign Office desire to postpone and his mark has been on this week's attempts to stall discussion of feder- alism. 'I'm becoming much more of a Gaullist these days,' he said to a colleague recently. 'I think the Community has got about as far as I envisaged it.'

The Foreign Secretary has what the Tories call 'bottom', that indefinable com- bination of backbone and good judgment believed to characterise a wise governor. This will soon be seen in the glare of television cameras, when he bats for Bri- tain not just in Luxembourg, but at next month's meeting in London of the world's seven leading industrial nations.

Few foreign secretaries since Curzon have had the influence or command Mr Hurd has now. He and his department have dictated what Britain wants on the agenda for both summits (for years, under Mrs Thatcher, such things were, ipso facto, prime ministerial prerogatives). Mr Hurd pioneered the idea that the Luxembourg summit should be a 'general stocktaking', in the hope of keeping the temperature down. The idea looks like being ignored.

The mandarins of the Foreign Office are overjoyed at the way in which their depart- ment has been able to shape foreign affairs since Mrs Thatcher's demise. Any new prime minister was bound to be less of a self-starter in foreign affairs than she was, but Mr Major's own relative youth and inexperience have made him especially dependent on the Foreign Office. That the Foreign Office has quickly reacquired so much of its old status is, however, princi- pally due to the qualities of the Foreign Secretary.

He and Mr Major have what is described by everyone who witnesses it as a 'very happy' relationship. Mr Hurd will not have to look over his shoulder at the summits in case the Prime Minister is departing from the agreed line, because such is the Foreign Secretary's influence that there will be no departure from the agreed line. There is no rancour that Mr Major beat Mr Hurd to the leadership last November. Mr Hurd was a reluctant candidate, but his close associates claim he was not as reluctant as legend has it.

'I didn't vote for Douglas because he didn't want the job,' is a popular refrain among his colleagues. Yet one of his campaign team says: `To start with he did not want to consider that Mrs Thatcher might lose. When she had withdrawn, and he was pressured to stand, Douglas hank- ered after an agreement between himself and Major to field one anti-Heseltine candidate. The thought of being Prime Minister grew on him. It would be wrong to say there was no element of disappoint- ment at the final result. However, he just shrugged his shoulders and carried on.'

In an attempt to improve his chances, Mr Hurd tried to play down his social origins, muttering at one stage that 'my father was a tenant farmer farming 500 acres of not particularly good hill land.. . we weren't poor. . . but there would be no question of him being able to send me to Eton if I hadn't won a scholarship'. 'The trouble with Douglas,' retorts a former cabinet colleague, is that he thinks we've all got 500 acres.' During the campaign the two 'rivals', Messrs Major and Hurd, spoke every day. Mr Hurd was taken with Mr Major when the latter was Chief Secretary to the Treasury, and saw him as an upholder of old Tory values. Mr Hurd took his junior colleague out for the occasional lunch at Mijanou, one of the smarter Westminster restaurants, and once Mr Major became Chancellor and Mr Hurd Foreign Secretary (on the same day, when Nigel Lawson resigned) a fortnightly breakfast was instituted. His heart was not, therefore, broken when his protégé beat him in the race to be Prime Minister.

Their regular discussions now, in the words of one official, `go much further than foreign affairs'. Mr Hurd has been depressed by the Tories' decline, but has not lost his reputation for loyalty. What he privately thinks about Mr Major's handling of that decline is a matter for speculation. He has not been active in domestic politics, mainly because he is not much interested in them, though this lack of interest has offended colleagues whose horizons are narrower and who feel he should do more. It seems certain he will.

Everybody who knows Mr Hurd knows he loves being Foreign Secretary, not because he is vain but because this is one of the most exciting periods in British foreign policy for half a century. No one, though, expects him to do the job for more than another couple of years, provided the electorate leaves his party in office that long. He needs to make some money, mainly to educate the young children of his second marriage. He wants to do more writing — he has collaborated on several thrillers, but wants to write more non- fiction. An earlier work, An End to Prom- ises, about his time with Heath, is highly regarded. Unlike most of his colleagues, Mr Hurd reads books, so writes well. He stopped a recent cabinet meeting in its tracks by an allusion to the novel Persua- sion, which caused most of his colleagues to ask what particular variety of arm- twisting he was talking about.

Paradoxically for a Foreign Secretary, he wants to spend much of his retirement travelling 'You must remember,' a col- league says, 'all his contemporaries are now ambassadors and high commissioners. I think he'd rather like to drift around the world and see them all.'

Such talk implies Mr Hurd is a grega- rious being, but that is far from the case. With the possible exception of the Tory MP Sir Dennis Walters he apparently has no intimate friends. 'Conversation with him is not easy,' says someone who knows him well. 'You have to make most of the running because he won't. He's deeply interested in the big issues but bored with trivia; and, sadly, much of what you have to talk about is trivia. He's a very serious man.'

A former King's Scholar at Eton, Mr Hurd is a very clever man too. He is also a very nice man, without malice or duplicity; heartbroken after his first wife left him, he nonetheless remains good friends with her, though for several years after the event he went deeply into his shell and seemed to suffer a complete personality change: hence his impermeability now, and his unfussy devotion to his second wife and young family.

Douglas Hurd rates as the greatest success of his political career the work he did with Heath to obtain British entry to the EEC 20 years ago. He may yet have cause to revise that view.

Previous page

Previous page