Sculpture

Local hero

Bruce Boucher welcomes the opening of the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds Last year the Henry Moore Foundation was engaged in an disagreeable squabble with the late sculptor's daughter over struc- tural and display changes to Moore's home and studio at Perry Green in Hertfordshire. Though the dispute garnered a fair share of media coverage, it deflected attention from the remarkable achievements of the Foun- dation in the 15 years since it was estab- lished by the artist himself.

This was a pity, for the presence of the Foundation has been one of the few posi- tive developments in the recent lean years for the arts. Moore conceived of his Foun- dation as a means of promoting interest in art and especially sculpture, which ironical- ly has remained the Cinderella of the fine arts despite the achievements of Moore, Hepworth, Epstein and Frink in this centu- ry. The Foundation created a subsidiary body, the Henry Moore Sculpture Trust, in 1988, which was given the remit of further- ing interest in sculpture through collabora- tion with museums and universities, particularly in Moore's native Yorkshire. The Foundation now administers a capital fund of around £50 million, and both bod- ies have been active behind the scenes, endowing galleries and assisting in the pur- chase of works of art through grants now running at £1 million each year. Together with the National Museums and Galleries on Merseyside, they have funded the most modern centre for sculpture conservation in Europe in Liverpool and have also creat- ed lectureships and research fellowships at Leeds, York, and London Universities.

With the opening of the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds last month, the final stone in the arch erected by the Founda- tion has fallen into place. In addition to exhibition space, the new Institute will house a centre for the study of sculpture. It already supervises creative initiatives like the Yorkshire Sculpture Park near Wake- field, where famous and less well estab- lished sculptors' works are shown in the grounds of Bretton Hall, and a sculpture studio in Halifax, designed as a laboratory where artists can experiment with their works in a more informal atmosphere than that of the traditional gallery or museum.

The opening of the new gallery and study centre in Leeds strengthens the ties between the city and the Sculpture Trust and, together with the Tate Gallery in Liv- erpool and the National Museum of Pho- tography in Bradford. it is indicative of a shift in new museum initiatives away from London. Local councils and museums in the north have responded enthusiastically to such overtures, and the availability of

land and public grants has facilitated pro- jects like the Yorkshire Sculpture Park or the Albert Dock complex in Liverpool. Leeds City Council is making a significant contribution towards the running costs of the exhibition and educational programmes of the Trust's new building. Indeed, the his- toric link between the city and Henry Moore is now visibly expressed by the new building, which flanks the City Art Gallery on Leeds' main street, the Headrow, and is connected to it by a glass bridge.

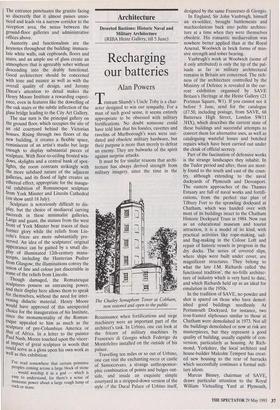

The building will be known as the Henry Moore Institute and represents an inven- tive adaptation of three Victorian wool merchants' houses on Cookridge Street, around the corner from the city hall and art gallery. Designed by Jeremy Dixon, Edward Jones and Building Design Part- nership, the new structure preserves the facades of the Victorian terrace while re- orienting their interior towards the princi- pal entrance on the Headrow. The new façade epitomises the building behind, a reticent but handsome essay in black gran- ite, with just a hint of crenellation above.

View of the new Henry Moore Institute in Leeds The entrance punctuates the granite facing so discreetly that it almost passes unno- ticed and leads via a narrow corridor to the reception area, the nexus between the ground-floor galleries and administrative offices above.

Austerity and functionalism are the keynotes throughout the building: immacu- late white walls, oak cupboards, floors and stairs, and an ample use of glass create an atmosphere that is agreeably sober without descending into the drably functional. Good architecture should be concerned with tone and nuance as well as with the overall quality of design, and Jeremy Dixon's attention to detail makes the Henry Moore Institute a rewarding experi- ence, even in features like the dowelling of the oak stairs or the subtle inflection of the glass bridge leading to the City Art Gallery.

The star turn is the principal gallery on the ground floor, which occupies the site of an old courtyard behind the Victorian houses. Rising through two floors of the new building, it creates a flexible space, reminiscent of an artist's studio but large enough to display substantial pieces of sculpture. With floor-to-ceiling frosted win- dows, skylights and a central bank of spot- lights, the room contrasts strikingly with the more subdued nature of the adjacent galleries, and its flood of light creates an ethereal effect, appropriate for the inaugu- ral exhibition of Romanesque sculpture from York Minster and Lincoln Cathedral (on show until 18 July).

Sculpture is notoriously difficult to dis- play, but the choice of mediaeval carving succeeds in these minimalist galleries. Large and gaunt, the statues from the west front of York Minster bear traces of their former glory while the reliefs from Lin- coln's frieze are more substantially pre- served. An idea of the sculptures' original appearance can be gained by a small dis- Play of illuminated 12th-century manu- scripts, including the Hun terian Psalter from Glasgow; the illuminations convey the union of line and colour just discernible in some of the reliefs from Lincoln.

Though damaged, the Romanesque sculptures possess an entrancing power, and their display here allows them to speak for themselves, without the need for inter- vening didactic material. Henry Moore would have approved of this unexpected choice for the inauguration of his Institute, since the monumentality of the Roman- esque appealed to him as much as the sculpture of pre-Columbian America or that of Africa. In a letter to the painter Paul Nash, Moore touched upon the viscer- al Impact of great sculpture in words that could serve as a gloss upon his own work as Well as this exhibition:

I've read somewhere that certain primitive Peoples coming across a large block of stone • . would worship it as a god — which is easy to understand, for there's a sense of immense power about a large rough lump of rock or stone.

Previous page

Previous page