Farewell in Madrid

John Organ

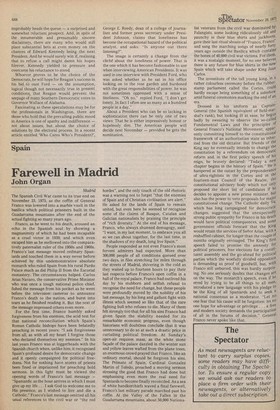

The Spanish Civil War came to its true end on November 23, 1975, as the coffin of General Franco was lowered into a marble vault in the basilica which political prisoners built in the Guadarrama mountains after the end of the actual fighting so many years ago.

Franco, as he went to his death, aroused an echo in the Spanish soul by showing a magnanimity of which he had been incapable as a cruel victor in 1939, and which even escaped him as he mellowed into the comparatively paternalist ruler of the 1950s and 1960s. Franco's last message moved ordinary Spaniards and touched them in a way never before achieved by this undemonstrative absolute monarch who ruled Spain from his rural Pardo Palace much as did Philip II from the Escorial monastery. The circumstances helped. Carlos Arias Navaro, the conservative Prime Minister who was once a tough national police chief, fished the message from his pocket as he went before the television cameras to announce Franco's death to the nation, and burst into tears as he finished reading it. But the text of the message impressed others even more.

For the first time, Franco humbly asked forgiveness from his enemies, the acid test for that national reconciliation which Spain's Roman Catholic bishops have been belatedly preaching in recent years: "I ask forgiveness from all, as with all my heart I forgive those who declared themselves my enemies." In his last years Franco was at loggerheads with the Spanish church when, unlike him, it recognised Spain's profound desire for democratic change and it openly campaigned for political freedoms. Not for nothing have scores of priests been fined or imprisoned for preaching bold sermons. In this light must be viewed the opening words of Franco's last message — "Spaniards: as the hour arrives in which I must give up my life ... I ask God to welcome me to His presence, as I wished to live and die a Catholic." Franco's last message omitted all his usual references to the civil war or "the red hordes", and the only touch of the old rhetoric was a warning not to forget "that the enemies of Spain and of Christian civilisation are alert." He asked for the lands of Spain to remain united, but even here he seemed to' recognise some of the claims of Basque, Catalan and Galician nationalists by praising the principle of "rich diversity." At the end of his message, Franco, who always shunned demagogy, said: "1 want, in my last moment, to embrace you all so we can shout together, for the last time, in the shadows of my death, long live Spain."

People responded as not even Franco's most fervent admirers had expected. More than 300,000 people of all conditions queued over two days, in files stretching for miles through the streets of Madrid, shivering in the cold as they waited up to fourteen hours to pay their last respects before Franco's open coffin in a hall of the royal palace. Franco had outlived his day by his stubborn and selfish refusal to recognise the need for change, but these people were profoundly moved by the nobility of his last message, by his long and gallant fight with illness which seemed so like that of the rare fighting bull who refuses to die. Many of them felt strongly too that for all his sins Franco had given Spain the stability needed for its remarkable economic progress, even though historians will doubtless concludethat it was unnecessary to do so at such a drastic price in curtailing political freedom. At Sunday's open-air requiem mass, as the white stone façade of the palace dazzled in the winter sun and yellow leaves wafted from the plane trees, an enormous crowd prayed that Franco, like an ordinary mortal, should be forgiven his sins. The Primate of Spain, Cardinal Gonzalez Martin of Toledo, preached a moving sermon stressing the good that Franco had done but emphasising even more the real need for Spaniards to become finally reconciled. As a sea of white handkerchiefs waved a final farewell, Franco's last military parade marched past his coffin. At the Valley of the Fallen in the Guadarrama mountains, about 50,000 Nationa

list veterans from the civil war dominated by Falangists, some looking ridiculously old and paunchy in their blue shirts and jackboots: gave their last ritual shouts of "Franco, Franco' and sang the marching songs of nearly fortY years ago outside the Basilica which contains the bones of 40,000 civil war victims. For them, it was a nostalgic moment, for no one believes there is any future for blue shirts in the new Spain which will take shape under King Juan Carlos.

The investitute of the tall young king, in a rather colourless ceremony before the rubber' stamp parliament called the Cortes, could hardly escape being something of a sideshow amid funeral ceremonies marking the end of an era.

Dressed in his uniform as Captain' General (the Spanish equivalent of field_marshal's rank), but looking ill at ease, he began badly by swearing to observe the so-called Fundamental Laws and the principles of General Franco's National Movement, apparently committing himself to the constitutional framework of an authoritatian state as inherited from the old dictator. But friends of the King say he eventually intends to change the constitution by a referendum on democratic reform and, in the first policy speech of his reign, he bravely declared: "Today a new chapter begins in the history of Spain." He is hampered at the outset by the preponderance of ultra-rightists in the Cortes and in the fourteen-man Council of the Realm, the constitutional advisory body which not onlY proposed the short list of candidates if he decides to appoint a new prime minister, but also has the power to veto proposals for major constitutional change. The Catholic daily Yn, which has long campaigned for democratic changes, suggested that the unexpectedlY strong public sympathy for Franco in his death would have political consequences, and solve government officials forecast that the King would retain the services of Senor Arias, with a reshuffled cabinet, for longer than the couple a months originally envisaged. The King's first speech failed to promise. the amnesty for political prisoners, free elections for a constituent assembly and the go-ahead for political parties which the woefully divided opposition is demanding as proof of goodwill, but, with Franco still unburied, this was hardly surprising. No one seriously doubts that changes are on the way. The monarch's speech, even if he erred by trying to be all things to all men, introduced a new language with his pledge to be the King of all Spaniards and to seek a national consensus as a moderator. "Let nn one fear that his cause will be forgotten: let no one hope for advantage or privilege . . a free and modern society demands the participation of all in the forums of decision." General Franco never spoke like that.

Previous page

Previous page