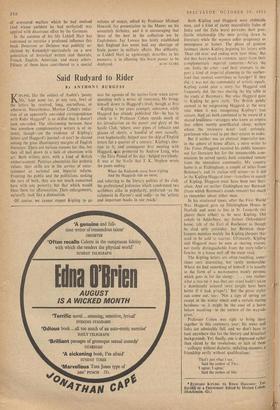

Said Rudyard to Rider

By ANTHONY BURGESS

KIPLING, like the subject of Auden's 'penny life,' kept none (or, at any rate, few) of the letters he received, long, marvellous, or otherwise. Nevertheless. Morton Cohen's redac- tion of an apparently one-sided correspondence with Rider Haggard* is so skilful that it doesn't look one-sided. The relationship between these two somehow complementary writers is of in- terest, though—on the evidence of Kipling's letters and Haggard's journal—it can't be classed among the great illuminatory margins of English literature. There are various reasons for this, but they all boil down to a lack of obsession with art. Both writers skirt, with a kind of British embarrassment, Paterian obscenities like aesthetic values; their skills are in the service of enter- tainment or national and imperial reform. Fronting the public and the politicians, seeking the ears of both, they are not much concerned here with any posterity but that which would bless them for afforestation. Their enlargements, naturally, look like a diminution.

Of course, we cannot expect Kipling to go

into the agonies of the sestina-form when corre- sponding with a writer of romances. He brings himself down to Haggard's level, though at first --Kipling is ten years younger, unknown, while Haggard has already published She—he has to climb to it. Professor Cohen spends much of his introduction on the power and glory of the Savile Club, 'where, over pipes of tobacco and glasses of sherry, a ' handful of men casually, even haphazardly, helped steer the ship of English letters for a quarter of a century.' Kipling's elec- tion to it, and consequent first meeting with Haggard, was promoted by Andrew Lang, who —the Ezra Pound of his day—helped everybody. It was at the Savile that J. K. Stephen wrote the poem ending: When the Rudyards cease from kipling And the Haggards ride no more, and referring to the literary politics of the club, the professional jealousies which condemned two scribblers alike in popularity, preferred—as the columnist in Harper's said sadly—to the 'artistic and important books in our reach.'

Both Kipling and 'Haggard were clubbable men, and a kind of yarny masculinity (tales of India and the Zulu wars) pervades their post- Savile relationship (the men getting down to literature while the women suffer pregnancy or menopause at home). The phase of greatest

intimacy shows Kipling ,begining his letters with 'Dear old man' and ending with ever thine.' But did they have much in common, apart from their complementary mperial concerns— Africa the one. India the other --and their lttempts to im- port a kind of imperial planning to the mother- land that seemed sometimes so foreign? If they did. it was not the community of artistic equals. Kipling could plan a story for Haggard and frequently did, the two sharing the big table in the study at Bateman's. But what Haggard gave to Kipling he gave early. The British public seemed to be outgrowing Haggard at the very time when it was recognising Kipling's true stature. And yet both continued to be aware of a shared loneliness—strangers who knew an empire that others merely pontificated about. writers whom the reviewers never took seriously, gentlemen who tried to put their estates in order.

But if neither was an abstract imperialist nor, in the sphere of home affairs, a mere writer to The Times (Haggard received his public honours not for literature but for the innumerable com- missions he served upon), both remained remote from the immediate community. My country home is at Etchingham, a couple of miles from Bateman's, and its station still serves--as it did in the Kipling-Haggard time—travellers in search of Kipling. Haggard must have been met there often. And yet neither Etchingham nor Bum 1,1, (from which Bateman's stands remote) has much to remember about either man.

In his straitened times, after the First World War, Haggard gave up Ditchingham House in Norfolk and went to live in St. Leonards (no ghosts there either) to be near Kipling. Old yokels in Adderbury, my former Oxfordshire home, talk of the Earl of Rochester as though he died only yesterday, but Burwash shop- keepers mention mainly the Kipling cheques that used to be sold to tourists. Ultimately, Kipling and Haggard must be seen as sharing visions, not easily distinguishable from the story-teller's fancies, in a house well off the main road.

The Kipling letters are often touching, some- times very interesting, but rarely memorable. Where we find something of himself it is usually in the form of a no-nonsense manly persOna which goes in for the slangy: . . one realises what a toss-up it was that our creed hadn't taken a dominantly oriental twist (might have been better if it had, p'raps1).' But the prose stylist can come out, too: 'Not a •sign of spring yet except in the winter wheat and a certain staring hardness—as it might be the coat of a horse before moulting—in the texture of the wayside grass.'

Professor Cohen was right. to bring these together in this centenary year; his notes and links are admirably full, and we don't have to look anywhere else for the literary and historical' backgrounds. Yet, finally, one is depressed rather than elated by the revelations, or lack of them —colloquy without dialectic, unfailing niceness, 3 friendship eerily without qualifications: 'That's just what I say,' Said the author of They. 'I agree; I agree,' Said the author of She.

•■••••••

*1%OTARD KIPLING TO RIDER HAGGARD: TIlt RECO op to FRIENDSHIP. Edited by Morton Cohen. (Hutchinson, 42s.)

Previous page

Previous page