MOURNING BECOMES EUROPA

France and Germany have good historical reasons for pressing ahead with European integration. We ignore

this at our peril, argues Timothy Garton Ash The point of this story is not that the Federal Republic of Germany necessarily has a 'federalist' approach to European Integration. The overall West German position is far more complicated than that. The point is that a German official close to the centre of power should think the question, 'How do you imagine Europe in 50 years' time?' interesting and important to raise, not in some grand set-piece speech for intellectuals, but in an informal, private discussion between people who will make real policy decisions today and tomorrow. The point is further that his counterpart on

the Quai d'Orsay would not have been startled by the question (indeed there are three German officials on permanent secondment to the Quai d'Orsay) and would have given an answer much closer to his own. The Channel is still several hundred miles wide.

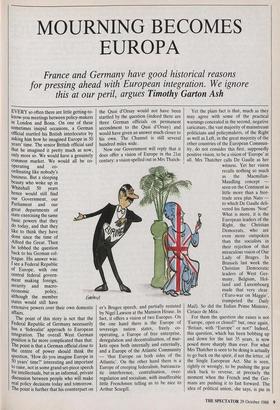

Now our Government will reply that it does offer a vision of Europe in the 21st century: a vision spelled out in Mrs Thatch- er's Bruges speech, and partially restated by Nigel Lawson at the Mansion House. In fact, it offers a vision of two Europes. On the one hand there is the Europe of sovereign nation states, freely co- operating, a Europe of free enterprise, deregulation and decentralisation, of mar- kets open both internally and externally, and a Europe of the Atlantic Community — 'that Europe on both sides of the Atlantic'. On the other hand there is a Europe of creeping federalism, bureaucra- tic interference, centralisation, over- regulation and socialism, with insufferable little Frenchmen telling us to be nice to Arthur Scargill. Yet the plain fact is that, much as they may agree with some of the practical warnings concealed in the second, negative caricature, the vast majority of mainstream politicians and policymakers, of the Right as well as Left, in the great majority of the other countries of the European Commun- ity, do not consider this first, supposedly positive vision, to be a vision of 'Europe' at all. Mrs Thatcher calls De Gaulle as her witness. Yet her vision recalls nothing so much as the Macmillan- Maudling concept -

seen on the Continent as little more than a free- trade area plus Nato — to which De Gaulle deli- vered his famous 'Non!' What is more, it is the European leaders of the Right, the Christian Democrats, who are even more outspoken than the socialists in their rejection of that miraculous vision of Our Lady of Bruges. In Brussels last week the Christian Democratic leaders of West Ger- many, Belgium, Hol- land and Luxembourg made that very clear. (`Euro-war on Maggie', trumpeted the Daily Mail). So did the Italian Prime Minister, Ciriaco de Mita.

For them the question she raises is not `Europe, open or closed?' but, once again, `Britain, with "Europe" or not?' Indeed, this question, which has been bobbing up and down for the last 35 years, is now posed more sharply than ever. For what Mrs Thatcher is seen to be doing is actually to go back on the spirit, if not the letter, of the Single European Act. She is seen, rightly or wrongly, to be pushing the gear stick back to reverse, at precisely the moment when the French and the Ger- mans are pushing it to fast forward. The idea of political union, she says, is pie in the sky and anyway 'people don't want it'.

That there is a yawning gulf between words and deeds in the enterprise of European integration can hardly be de- nied. This does not mean either that the words are unimportant to those who speak them, or that there are no deeds at all. Indeed, one may surmise that one of the reasons she has spoken out so fiercely now is that she has woken up, a little late, to the fact that the Single European Act and the whole process of integration are not just words. Her direct, personal experience of the politics of the European Community over the last ten years has obviously reinforced her instinctive scepticism about the chances of this process leading any- where at all. Yet ten years in Europe is a short time. One of her weaknesses is that she, unlike Churchill, rarely looks back 50 years rather than ten, and has no sense at all of that larger European history of greatness and tragedy out of which the idea of a European Community sprang.

Compare and contrast the flat, trium- phalistic, 'island story' platitudes that open her Bruges speech with the wonderful depth, sympathy, tragic sense and historic- al range of Churchill's great European speeches at Zurich in September 1946 or at the Albert Hall in May 1947. Remember also that in the latter he said: 'It is for France and Britain to take the lead.' Of course, when it came to the point, the old man put relations with the Commonwealth and a largely imaginary 'special rela- tionship' with the United States before the joint construction of a United Europe. Konrad Adenauer asked him to take the lead in that enterprise. Churchill declined. In his memoirs Adenauer describes their conversation in 1953. It was then that Churchill sketched on the back of a menu card his famous image of three intersecting circles, which he marked 'USA', 'United Europe' and, if I decipher it correctly, 'Br Em.' (i.e. British Empire. The card is reproduced in the memoirs).

So France took the lead. De Gaulle did in 1958 what Churchill declined to do in 1953; and was richly rewarded. 'I intended that France should weave a network of preferential ties with Germany,' he writes in his memoirs, and he did just that. (One of these 'preferential ties' was the CAP.) Of course De Gaulle subsequently became a great obstacle to further European in- tegration: indeed a far larger obstacle than Mrs Thatcher has ever been. German politicians tend to forget the De Gaulle of circa 1965-1968. But Mrs Thatcher seems to have forgotten the De Gaulle of 1958- 63, when, between his meeting with Ade- nauer at Colombey-les-deux-Eglises (a Shakespearian scene) and the signing of the Elysee- Treaty, the two grand old men laid what both countries still consider to he the political foundations of 'Europe'. The French and German metaphors are charac- teristically different. German politicians talk about the Franco-German 'Achse', which means either 'axis' or 'axle'. The Franco-German axle, they say, must be the motor of European unification, and never mind the mixed metaphors. The French talk about the Franco-German 'couple', which gives rise to an altogether more enjoyable set of metaphorical images. But marriage, seduction or merely motoring, the basic message is the same.

This was true of Adenauer and De Gaulle. It was true of Schmidt and Gis- card. Even discounting for both leaders' retrospective idealisation of their rela- tionship (carried on, incidentally, in fluent English), the Giscard-Schmidt couple nonetheless produced at least two bonny wee babes, called EMS and 'ecu'. And now we have Kohl and Mitterrand, holding hands over the graves at Verdun. Well, nobody is going to hold hands with Mrs Thatcher, thank you very much. But sym- bolic politics apart, this latest couple have, in just the last year, and on top of the multilateral initiatives which the German presidency pushed through in Brussels, come up with a Franco-German joint brigade, planS for a joint defence council and a joint finance council (which, Bundes- bank reservations duly noted, should go before both parliaments later this or early next year), more talk about the all- important subject of co-ordinating approaches towards the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, and a proposal for a joint embassy in Ulan Bator. These initiatives are of varying significance. Crucial as Outer Mongolia plainly is to the future shape of world politics, Britain may not feel an immediate necessity to Europeanise its diplomatic representation there. The yaks can wait.

More seriously, it may fairly be observed that the French still have a long way to go just to catch up with the daily intimacy and real, military significance of the Anglo- German security relationship: a middle- aged marriage if ever there was. The most immediate challenge is clearly in the eco- nomic and financial sphere. Yet it would he extremely foolish to assume that even the embassy in Outer Mongolia does not presage more serious things to come. Today, Ulan Bator, but who knows, perhaps tomorrow San Salvador, or Nairo- bi, or Damascus.

Irrespective of sentiment or idealism we all have at least two strong contemporary reasons for wanting further, faster Euro- pean integration, particularly in economic and security policy. Put very crudely, these are the fear that the Americans will do less (militarily) and the fear that the Japanese will do more (economically). But on top of these shared reasons, the French and the Germans continue to have their own his- torical reasons, which recent developments have rather reinforced than otherwise. Both have a more direct and traumatic experience of war and occupation. The cry of 'never again!' meant more, to more people, in 1945, and still does. The French intention was always, by embracing the Germans, also to contain them. The more tempted the Germans have seemed to be by 'neutralism' or Gorbachev, the stronger this motive has become in Paris.

Curiously enough, Adenauer shared precisely this intention. After his experi- ence of German history in the first half of the 20th century he was deeply sceptical about his own people's capacity to steer a steady course unaided. 'My God,' he cried to two close associates, in an evening of despair after the failure of the planned European Defence Community in 1954, `I don't know what my successors will do, if they are left to themselves, if they do not have firmly delineated lines to travel down, if they are not bound in to Europe. . . For all the achievement and stability of the intervening 30 years, I am assured by someone in a position to know that Chan- cellor Kohl, professedly 'Adenauer's grandson', still feels something of this motivating doubt.

At the same time, it is less difficult for the French and the Germans to contem- plate major changes in their political struc- tures, by acts of will and written treaties, for the simple reason that they have had so many such changes already; unlike Britain. The ghost of Edmund Burke would be appalled by their recent histories. The mere 30-year-old regime which Francois Mitterrand heads is, after all, already the Fifth Republic. (Lady Bracknell to Madame Liberte: `To have one republic, Madame Liberte, may be regarded as a misfortune; to have five looks like careless- ness.') And Germany has had more regimes than Elizabeth Taylor has had husbands: two score of principates, Prus- sia, Bavaria, Saxony, Bismarckian Reich, Wilhelmine Reich, Weimar Republic, Third Reich, Federal Republic and Demo- cratic Republic.

It is of course eminently possible that the Franco-German motor will once again stall, whether because of French fears about loss of national sovereignty in the West, or because of German hopes of regaining more national sovereignty in the East, or for any of a host of reasons. It is also perhaps just theoretically conceivable that Britain should at some point say: 'All right, we simply do not want to go any further down this road. You do. Let us then have a two- or multi-speed Europe. The British oak cannot be cut into a continental lime. But we can make sensible arrangements for close co-operation within a genuine common market.' Certainly in Bonn and Paris they are again talking about the two-speed Europe.

What is unforgiveable is to act as if we will never have to face such hard choices. On present trends, we may well do -- and in a matter of years rather than decades.

Previous page

Previous page