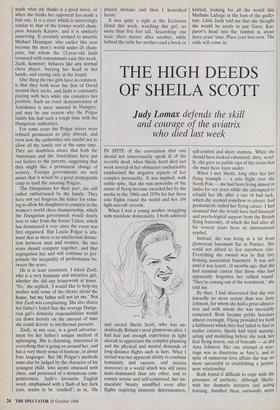

THE HIGH DEEDS OF SHEILA SCOTT

Judy Lomax defends the skill

and courage of the aviatrix who died last week

IN SPITE of the convention that one should not unnecessarily speak ill of the recently dead, when Sheila Scott died last week several of her obituaries uncharitably emphasised the negative aspects of her complex personality. It was implied, with subtle spite, that she was unworthy of the status of flying heroine awarded her by the media in the 1960s and 1970s for her three solo flights round the world and her 104 light-aircraft records.

When I was a young mother struggling with mundane domesticity, I both admired and envied Sheila Scott, who was un- doubtedly Britain's most glamorous pilot. I had had just enough experience in light aircraft to appreciate the complex planning and the physical and mental demands of long-distance flights such as hers. What I envied was her apparent ability to combine femininity and success, and success moreover in a world which was still more male-dominated than any other, and to remain serene and self-composed, her im- maculate beauty unruffled even after flights requiring immense determination, self-control and sheer stamina. When she should have looked exhausted, dirty, scruf- fy, she gave no public sign of the strain that she must have been under.

When I met Sheila, long after her last flying triumph — a solo flight over the North Pole — she had been living almost in limbo for ten years while she attempted to rebuild her life after a run of bad luck, which she seemed somehow to attract, had prematurely ended her flying career. I had assumed that she would have had financial and psychological support from the British flying fraternity, of which she had after all for several years been an international symbol.

Instead, she was living in a far from glamorous basement flat in Pimlico. She could not afford to live anywhere else. Everything she owned was in that tiny housing association basement. It was not until it was learnt, 18 months ago, that she had terminal cancer that those who had apparently forgotten her rallied round. `They're coming out of the woodwork,' she told me.

By then, I had discovered that she was inwardly no more serene than was Amy Johnson, for whom she had a great admira- tion and with whom she was inevitably compared. Both became public heroines almost overnight. Flying provided for both a fulfilment which they had failed to find in earlier careers; Sheila had tried nursing, acting and modelling before she took her first flying lesson, out of bravado — as did Amy Johnson. Her one attempt at mar- riage was as disastrous as Amy's, and in spite of numerous love affairs she was no more successful in establishing a perma- nent relationship.

Both found it difficult to cope with the pressures of publicity, although Sheila, with her dramatic instincts and acting training, handled these outwardly more easily than did her predecessor. Her de- tractors — and she had many, despite or perhaps even because of her glamorous public image — would no doubt add that neither was a particularly good pilot. This criticism would be unfair to Sheila. Where Amy muddled her way to Australia with the optimism of ignorance, Sheila knew exactly what she was doing.

Why she was doing it was another matter. She was intensely competitive, but at the same time lacked confidence in herself, except in the air, where she found a spiritual satisfaction not easily under- stood by the earthbound majority. She was often accused of courting publicity, which indeed she enjoyed, and needed if she was to recoup some of the costs of her gruelling self-inflicted endurance tests. But without a thoroughly cool and professional approach to flying, she would not have won many of the world's most prestigious flying awards.

So obsessional was her attitude to flying, and her need to prove herself by outflying others, that she sacrificed her private life to the financial demands of her aircraft. In spite of assertions to the contrary, she received little in the way of sponsorship, financing her long-distance flights largely by using her public image to gain lecturing engagements and was always on the verge of poverty. Her only professional regret, when she looked back over her life shortly before she died, was that she had never achieved financial security, although she often said wistfully that she would have liked the companionship, of a permanent live-in partner — not, however, another husband, and certainly not children.

She knew that she was dying, and could even joke about it. But she refused to give in easily. Throughout her increasingly painful battle with cancer, she maintained her dignity, her independence, her femi- ninity, and her right to enjoy herself.

However ill she was, Sheila was always fun to be with. Her courage proved that she still had plenty of the determination and stamina which had enabled her to make her record-breaking flights.

I dreamt about her the night before she died —'she would have attributed this to extra-sensory perception, in which she had

a firm belief. In my dream, she was already dead, in a sunfilled room opening onto a

courtyard of flowers. A number of her friends drifted in. 'Let's all drink cham- pagne,' someone suggested. 'That's what Sheila would want us to do.' As I raised my glass, Sheila opened one eye and winked conspiratorially at me, just as she had often done while she was alive.

Only a few hours later, I was with her in the Royal Marsden Hospital when her laboured breathing gradually became easier and stopped altogether. She looked peaceful, which was a relief; she had fought so hard to stay alive that I had feared that peace would elude her in death as it had in life.

Previous page

Previous page