THE BIRTH OF BAZZA

NICHOLAS GARLAND

IN the fourth episode of his existence as a comic strip character, Barry McKenzie, fresh off the boat from Australia, writes a letter introducing himself to an English family.

Dear Mr and Mrs Gort, I am now in your old country and am desirous of seeing you for an afternoon's duration approximately in the vicinity of Saturday afternoon.

You will doubtless remember the delicious food parcels Mum and us sent you during the Period of Hostilities, also the Winston Chur- chill calendar Dad sent old Mr Gort approx- imately in the vicinity of Xmas 1943.

Your obedient servant, Love, Barry McKenzie

Sometime later he writes the following autobiographical sketch.

I was born in Sydney of parents. My grannie used to let me smell her camphor chest. Once we had a barbecue in the bush and the blowies got Mum's T-bone.

Whenever we had a stinkeroo of a day we used to go down the beach and Mum put zinc cream on our noses and Kwik-tan and muck so the sand got stuck all over our legs and going home the seat of the car used to burn you like buggery.

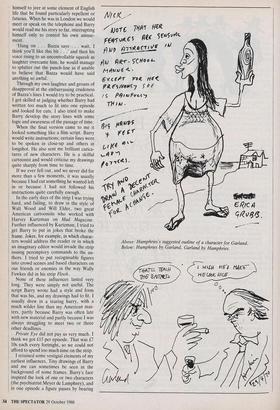

This language filled me with pleasure. I would learn such extracts by heart and speak them to myself like poems. I still laugh out loud when I read them, and to an extraordinary extent they remind me of my own Australasian childhood in New Zea- land. It is not just the slang words such as `stinkeroo' that fire my memory, it is the strangulated attempts at sounding classy, coupled with the touching artlessness of ‘. . . the back seat of the car used to burn you like buggery'. The wondering pleasure I took from McKenzie's language was analogous to the special delight that comes when one of A drawing by Barry Humphries your children displays a completely unex- pected talent.

It was 1964 and not many journals, other than Private Eye where the strip appeared, would have published such words as 'buggery'. The strip eventually got too shocking even for the Eye, and one awful day about ten years later Richard Ingrams could not bring himself to publish the next episode and it all came to an end.

I always thought that I had invented Barry McKenzie. It is true that Peter Cook had suggested as a comic strip hero a young Australian visiting London, but I named and drew him. By the time I took the character to Barry Humphries, again on Peter Cook's advice, to ask him to write the strip I felt quite unreasonably prop- rietorial about him. I was enormously pleased that Barry liked the idea straight away and I remember being surprised by how quickly he began to invent speeches and adventures for my hero.

Recently I discovered that the reason McKenzie was immediately absorbed, fully understood, into Barry's mind was that a few years earlier, in 1960, Barry had recorded a series of comic monologues recounting the experiences of another young Australian in London called Buster Thompson. Buster had become Bazza, huge chin, wide-brimmed hat, double- breasted suit and all.

From our first meeting Barry and I worked together very easily. In all the time we worked together we rarely spent very long deciding on the direction a new episode might take. Barry would introduce a new character or situation without neces- sarily knowing how the story would de- velop. He was more interested in setting up a joke or making an opportunity for himself to jeer at some element of English life that he found particularly repellent or fatuous. When he was in London we would meet or speak on the telephone and Barry would read me his story so far, interrupting himself only to control his own amuse- ment.

`Hang on . . . Bazza says . . . wait, I think you'll like this bit . .' and then his voice rising to an uncontrollable squeak as laughter overcame him, he would manage to splutter out the punch-line as if unable to believe that Bazza would have said anything so awful.

Through my own laughter and groans of disapproval at the embarrassing crudeness of Bazza's lines I would try to be practical. I got skilled at judging whether Barry had written too much to fit into one episode and looked for cuts. I also tried to make Barry develop the story lines with some logic and awareness of the passage of time.

When the final version came to me it looked something like a film script. Barry would write instructions; certain lines were to be spoken in close-up and others in longshot. He also sent me brilliant carica- tures of new characters. He is a skilful cartoonist and would criticise my drawings quite sharply from time to time.

If we ever fell out, and we never did for more than a few moments, it was usually because I had cut something he wanted left in or because I had not followed his instructions quite carefully enough.

In the early days of the strip I was trying hard, and failing, to draw in the style of Walt Wood and Will Elder, two great American cartoonists who worked with Harvey Kurtzman on Mad Magazine. Further influenced by Kurtzman, I tried to get Barry to put in jokes that broke the frame. Jokes, for example, in which charac- ters would address the reader or in which an imaginary editor would invade the strip issuing peremptory commands to the au- thors. I tried to put recognisable figures into crowd scenes and based characters on our friends or enemies in the way Wally Fawkes did in his strip Flook.

None of these influences lasted very long. They were simply not useful. The script Barry wrote had a style and form that was his, and my drawings had to fit. I usually drew in a tearing hurry, with a much wilder line than my American mas- ters, partly because Barry was often late with new material and partly because I was always struggling to meet two or three other deadlines.

Private Eye did not pay us very much. I think we got £15 per episode. That was £7 lOs each every fortnight, so we could not afford to spend too much lime on the strip.

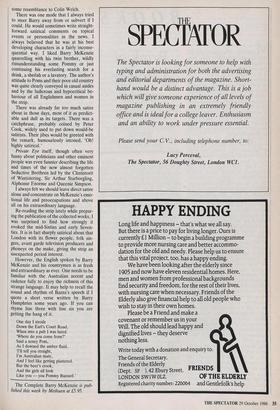

I retained some vestigial elements of my earliest influences. Tiny drawings of Barry and me can sometimes be seen in the background of some frames. Barry's face inspired the look of one or two characters (the psychiatrist Meyer de Lamphrey), and in one episode a figure passes by bearing Above: Humphries's suggested outline of a character for Garland. Below: Humphries by Garland, Garland by Humphries. some resemblance to Colin Welch.

There was one mode that I always tried to steer Barry away from or subvert if I could. He would sometimes write straight- forward satirical comments on topical events or personalities in the news. I always believed that he was at his best developing characters in a fairly inconse- quential way. I liked Barry McKenzie quarrelling with his twin brother, wildly misunderstanding some Pommy or just continuing his everlasting search for a drink, a sheilah or a lavatory. The author's attitude to Poms and their poor old country was quite clearly conveyed in casual asides and by the ludicrous and hypocritical be- haviour of all Englishmen and women in the strip.

There was already far too much satire about in those days, most of it as predict- able and dull as its targets. There was a catchphrase, probably coined by Peter Cook, widely used to put down would-be satirists. Their jibes would be greeted with the remark, humourlessly intoned, 'Oh! highly satirical.'

Private Eye itself, though often very funny about politicians and other eminent people was even funnier describing the life and times of the now almost forgotten Seductive Brethren led by the Clintistorit of Wintistering, Sir Arthur Starborgling, Alphonse Enorme and Queenie Simpson.

I always felt we should leave direct satire alone and concentrate on McKenzie's emo- tional life and preoccupations and above all on his extraordinary language.

Re-reading the strip lately while prepar- ing the publication of the collected works, I was surprised to find how strongly it evoked the mid-Sixties and early Seven- ties. It is in fact sharply satirical about that London with its flower people, folk sin- gers, avant garde television producers and phoneys on the make, giving the strip an unexpected period interest.

However, the English spoken by Barry McKenzie and his countrymen is as fresh and extraordinary as ever. One needs to be familiar with the Australian accent and cadence fully to enjoy the richness of this strange language. It may help to recall the sound and rhythm of Bazza's speech if I quote a short verse written by Barry Humphries some years ago. If you can rhyme line three with line six you are getting the hang of it.

One day I strode

Down the Earl's Court Road, When into a pub I was lured.

'Where do you come from?'

Said a nosey Porn, As I downed the amber fluid.

'I'll tell you straight, I'm Australian mate, And I feel like getting plastered.

But the beer's crook, And the girls all look Like you — you Pommy Bastard.'

The Complete Barry McKenzie is pub- lished this week by Methuen at £5.95.

Previous page

Previous page