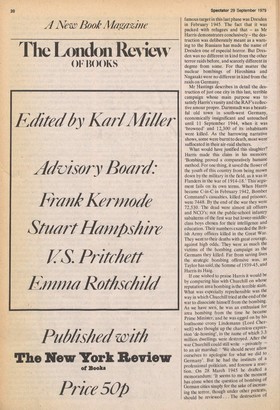

Books

Devastating and exterminating

Geoffrey Wheatcroft

Bomber Command Max Hastings (Michael Joseph £8.50) The subject of this enthralling book is one of the epic campaigns, and the greatest war crime, of the second World war. It describes how Great Britain created a vast force of heavy aircraft to bombard Germany in the belief that this would, on its own, bring victory. It did not do so. The contribution made by strategic bombing to the Allied victory is a complicated and probably unanswerable question. The only certain achievement was the destruction of most of the cities of Germany and the killing of some 600,000 Germans, almost all of them civilians. The human cost on the British side was 55,573 aircrew dead.

The story is especially British from the outset. The possibilities of air power had startled the combatant powers during the first World war. In other countries there were proponents of the doctrine of independent aerial bombing the Italian Douhet, the American Mitchell but only Great Britain formally embraced it. The Royal Air Force , was established as a separate service in 1917, with Trenchard its first chief of staff; and 'the heavy bomber was the visible expression of the RAF's determination to make a contribution to the war independent of the other two services, as was the weakness of its air ground and air-sea co-ordination techniques'. Mr Hastings adds that 'the pm-war RAF was geared to the execution of a strategic terror bombing campaign and this was the core of the Trenchard doctrine'.

That is perhaps too sweeping, for ambiguity surrounded the RAF's role from the beginning. In 1917 Winston Churchill had observed: 'We have seen the combative spirit of the people roused, and not quelled, by the German air -raids . . Therefore our air offensive should consistently be directed at striking at the bases and communications upon whose structure the fighting power of his armies . . depends. Any injury which comes to the civil population. . . must be regartled as incidental and inevitable.' In 1928 Air Vice Marshal Sir John Steel (later to be the first C-in-C of Bomber Command) could say: 'There has been a lot of nonsense tailked about killing women and children. Every objective I have given my bombers is a po int of military importance . . Otherwise the pilots, if captured, would be liable to be treated asewar criminals.' At much this time• British aircraft, commanded by a young officer called Arthur Harris, put down a risi ng of tribesmen (and women and chil, dre n) in Iraq by bombing them into submiss iO fl.

'The ambiguity was heightened by a confu sion about what bombers could, as well as what they should, do. Air war gripped the imagination of public and politicians in the inter-war years. The popular view, as well as the RAF doctrine, was expressed by Baldwin in a Commons debate of 1933: 'The bomber will always get through.' Thus the moral queltion was side-stepped. Fleets of bombers could sail unopposed to the enemy's territory in daylight;dropping their bombs just where they wanted, on the 'bases and communications'.

This doctrine was rendered completely meaningless during the Thirties by the development of the fast, well-armed monoplane fighter a development which took place on the British side with no thanks to the Air Ministry or the air marshals: but for private initiative there would have been no Spitfire or Hurricane in 1940. As the RAF discovered with calamitous cost in 1939-40, the bomber did not get through. The airmen had seen themselves as the new cavalry. In practice, flying Wellingtons and Whitleys in daylight against Messerschmitt fighters was all too like a cavalry charge against machine-gun posts. There was an answer. By 1943-4 the long-range fighter the Mustang had come into being, providing cover for the bombers deep inside Germany. Daylight precision bombing at last became possible. Until this technological breakthrough took place, the Air Ministry dismissed it as impossible.

In 1940 the RAF's pre-war promises were shown to be empty. It was still constrained from bombing larger rather than smaller targets. At the outbreak of war Roosevelt had appealed to the belligerents to renounce the bombing of civilians. The Daily Mail in January 1940 condemned proposals for bombing Germany: 'We should do nothing unworthy of our cause.' Sir Kingsley Wood, Secretary for Air, could deplore a planned attack with the words: 'Are you aware it is private property? Why, you will be asking me to bomb Essen next.' (These words are still sometimes quoted to show Wood in a ludicrous light. They seem to me to represent an eminently proper attitude.) The next turning point came with the fall of France. During the year when England stood alone, a powerful impetus was added to the RAFs traditio9a1 'belief in strategic bombing; there leas_ nothing else to do. Sensibilities 'hardened, and there were calls for revenge, It is a nice question maybe an idle one which side began the bombing of cities. The Luftwaffe's raids on Warsaw and Rotterdam followed the age-old bombardment of towns which stood in the way of a military advance. The misnamed 'Blitz' on British cities began in anticipation of an invasion, and it began five months after the RAF had first bombed cities in Germany. The balance is tilted by the fact, to which we will return, that the Luftwaffe was meant as a tactical force to co-operate with the army. It was ill-suited to the long-range heavy bombing for which the RAF was designed.

There was also the crucial personal factor of Churchill. His complicated personality was a mixture of humanity and ruthlessness, above all of impetuosity and aggression. The second phase of Bomber Command's offensive was launched, as Mr Hastings reminds us, because Churchill saw no strategic alternative. He knew that the British people did not want to surrender to Hitler; he knew too that they had no means of defeating him, until Hitler solved the problem himself by making war on the United States and Russia. In the meantime he followed the dangerous instinct that doing anything was better than doing nothing.

On 14 June 1940 bomber pilots were still reminded that 'bombs are not to be dropped indiscriminately', and in the same month a Government instruction to the Air Ministry said that attacks 'must be made to avoid undue loss of civil life in the vicinity of the target'. Yet Churchill could write on 8 July: 'There is only one thing that will bring Hitler down, and that is an absolutely devastating, exterminating attack by very heavy bombers on the Nazi homelanel . . . without which I do not see a way through' (my italics, his choice of words). That quotation is wellknown. Mr Hastings has produced many others, and the great merit of his book is that it is the first to have been written on the subject since the official records were opened. His method is to alternate chapters describing the strategic and political situation with chapters describing a given Bomber Command squadron on operations at a particular time. It is a technique which works very well (though I could have done without the 'human interest' pen-portraits of individual aircrew). Thus, the second phase of Bomber Command's war is illustrated by 10 Squadron stationed at Dishforth in Yorkshire in 1941. In this period the British were moving unmistakably towards 'strategic bombing', otherwise area bombing, or as the Germans would finally and most accurately call it, terror bombing. The bombers were, in theory, aimed at military and industrial targets but on 30 October 1940 the war cabinet had decided with the odious euphemism which was to characterise this whole story that 'the civilian population around the target areas must be made to feel the weight of the war'. The Whitleys of 10 Squadron sometimes attacked military targets, sometimes naval ones such as the U-boat yards in France (though the RAF displayed an almost pathological resistance to co-operating with the Royal Navy, even when it was clear in 1941-3 that the Battle of the Atlantic was the one battle where Great Britain might actually lose the war). But they were also now attacking cities in 'crash concentration'. What distinguished this phase, the 1941 offensive, was its utter ineffectuality. The bombers bombed because they had been built to bomb. Bombing in daylight was suicidal, so they bombed at night but they quite lacked the expertise or technology to do SO accurately. In August, the secretary of the war cabinet, D.M. Butt, conducted an indePendent survey which showed that fewer than one aircraft out of eight despatched was bombing within five miles of its target. It !ubsequently became clear that almost no Impact had been made on the German war economy, and that in 1940-1 more RAF aircrew than Germans had been killed. The Offensive was called off.

Now came the fateful decision. Bomber Command could not hit precise targets. It could not even, at that stage, reliably hit larger ones. Little damage had been done to German cities. RA,F casualties, though Proportionately severe, were not yet overwhelming. Webster and Frankland's The Strategic Air Offensive Against G er many has been described as the 'most ruthlessly impartial of all official histories' by A.J.P. Taylor. (Mr Taylor remains one of the most eloquent critics of the bombing Offensive, but one of the incidental effects of Mr Hastings's book is to show that the account of it inEnglish History 1914-1945 is inaccurate and tendentious.) But when Webster and Frankland say that there were now only two choices, area bombing or no bombing, they are oversimplifying the case. Mr Hastings points out there were other Options open. In fact, he is admirably judicious throughout, marshalling the facts with considerable forensic skill, though with less literary grace. (I might as well complain here about the production of the book. It is poorly printed, badly proof-read, inadequately indexed, and the references are provided in such a way as to make tl*m impossible to use. But that's nowadays).

As Mr Hastings says, there was a third choice. 'to persist, in the face of whatever difficulties, in attempting to hit precision targets', and 'a fourth and more realistic alternative: faced by the fact that Britain's bombers were incapable of a precision campaign, there was no compulsion upon the Government to authorize the huge bomber programme that was now to be undertaken. Aircraft could have been transferred to the Battle of the Atlantic or the Middle and Far East where they were so urgently needed. .

This is the vital point. There can be no exact calculation of what proportidn of the British war-economic effort Bomber Command absorbed — Taylor suggests a third. What is obvious is that every bomber produced meant other material not produced. And what is also indisputable is that the lack of other material gravely impaired the conduct of the war, first defensive, then offensive. There were barely enough fighters for the Battle of Britain. Admiral Cunningham, Who was in a good position to judge, thought that Crete could have been held with half a dozen more fighter squadrons, and it was lack of fighters that led to the sinking of the Prince of Wales and the loss of Singe pore. Coastal Command never had enough long-range aircraft for convoy duty. Later, the lack of landing craft and of tanks was one of the factors which delayed the invasion of Europe. All of this could reasonably be blamed on the massive production of bombers.

At all events the decision was taken for a great campaign of area bombing, a decision symbolised by the appointment of Sir Arthur Harris as C-in-C Bomber Command in February 1942. Harris was a commander of extremely strong personality, coarse and ruthless, single-minded in his aim: the systematic destruction of German cities. He successfully resisted all attempts to divert his bombers from this end, either to supporting the Navy or to what he dismissed as 'panaceas', bombing the German installations for producing synthetic oil or ballbearings. His new campaign was inaugurated on 28 March 1942 with the 234aircraft attack on Liibeck, a mediaeval town, strategically insignificant but in Harris's words, 'more like a fire-lighter than a human habitation'. Lubeck was burned to the ground, the first of many.

The new campaign was fought despite a slight but perceptible current of unease and protest. The public critics were Richard Stokes, the Labour MP, and Bishop Bell of Chichester, There were private protests. Lord Salisbury — not a left-wing pacifist — thought that German atrocities did not justify reprisals: 'We do not take the devil as our example'. Many who lived through the war will, in honesty, admit that they felt no misgivings at the time about the area bombing. Their consciences were not just numbed by the horror of total war. There was besides a policy of shameless official mendacity designed to conceal the great change in policy, the true nature of the offensive now being fought, Whatever may be said of Harris, he was utterly unhypocritical about his pursuit of death and destruction. Not so his political masters. Students of Question Time in the House of Commons will not be surprised to learn that Ministers of the Crown are given in wartime to telling lies even more outrageous and wilful than the ones they tell in peacetime. On 27 May 1943 Clement Attlee,the Deputy Prime Minister, replied amidst cheers: 'No, there is no indiscriminate bombing. As has been repeatedly stated in the House, the bombing is of those targets which are most effective from the military point of view.' On 31 March 1943, two days after Lubeck, Sir Archibald Sinclair, the Air Minister, had replied: `The targets of Bomber Command are always military', and he repeated this answer on 2 December. When they uttered these words both men knew them to be flagrant lies. Churchill, Attlee and Sinclair, as well as being colleagues in the Government, were also of course the leaders of the three great political parties. Less than one cheer for democracy, I think.

The third phase of the bomber war lasted from Harris's appointment until mid-1944. The Ruhr towns were attacked from March to June 1943, Hamburg from July to November. Berlin from November until March 1944. Hamburg was the first great display of the RAF's new method, the fire raid. Using much more sophisticated techniques of electronic navigation, of marking and of bombing, the city was first broken up by explosives — 'cookies' designed to blow open doors and windows — and then rained with incendiaries, Repeated raids overwhelmed the civil defence and fire services. Bomber Command attacked Hamburg on 24 July, again on 27 July, with American attacks between. The raid of the 27th created a vast firestorm, destroying 27 square kilometres of the city, and killing an estimated 42,000 people. Fifteen months later Harris would boast that Bomber Command 'has virtually destroyed 45 out of the leading 60 German cities'. This third phase is sometimes spoken of as Harris's time of supreme independence, but it was in the final phase, from the summer of 1944 to the end of the war, that his defiance of orders and the criminality of British bombing, reached their apogee. In the middle of 1944 the United States Army Air Force at last achieved the one great victory of the bombing war. Precision bombers struck at the oil plants, while their Mustang escorts successfully fought the German fighters. The Luftwaffe was deprived of aircraft, pilots and fuel, and became almost impotent.

Until now the bombing battle had been fought on something like equal terms. Although Bomber Command's Lancasters wrought terrible havoc on German cities the Luftwaffe nightfighters inflicted very heavy losses on the RAF: the nightfighters almost got the upper hand at the end of 1943. With the defeat of the Luftwaffe, the Allied air forces could do just what they wanted. Harris was ordered te join the attack on oil. He had always scorned 'panaceas', indeed any diversion of his forces from area bombing, and had had to be farced to contribute bombing capacity for the Normandy landings. He was determined to continue his independent campaign against cities, to prove that Bomber Command could win the war on its own, as he had always claimed. Now he refused to obey his orders, daring his superiors to dismiss him. They did not. The full extent of Harris's insubordination— and the Air Ministry's and Churchill's weakness — is revealed by Mr Hastings.

Instead, Harris continued on his own way, One undefended city after another was devastated from end to end by explosion and fire, 'browned' as the repellent RAF phrase had it. More bombs were dropped by Bomber Command in the last quarter of 1944 than in the whole of 1943. The most famous target in this last phase was Dresden in February 1945. The fact that it was packed with refugees and that — as Mr Harris demonstrates conclusively— the destruction was deliberately meant as a warning to the Russians has made the name of Dresden one of especial horror. But Dresden was no different in kind from the other terror raids before, and scarcely different in degree from some. For that matter the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were no different in kind from the raids on Germany. Mr Hastings describes in detail the destruction of just one city in this last, terrible campaign whose main purpose was to satisfy Harris's vanity and the RAF's collective amour propre. Darmstadt was a beautiful old town in south-west Germany, economically insignificant and untouched until 11 September 1944, when it was 'browned' and 12,300 of its inhabitants were killed. As the harrowing narrative shows, some were burnt to death, most were' suffocated in their air-raid shelters.

What would have justified this slaughter? Harris made this claim in his memoirs: 'Bombing proved a comparatively humane method. For one thing, it saved the flower of the youth of this country from being mown down by the military in the field, as it was in Flanders in the war of 1914-18.' This argument fails on its own terms. When Harris became C-in-C in February 1942, Bomber Command's casualties, killed and prisoner, were 7448. By the end of the war they were 72,530. The dead were almost all officers and NCO's; not the public-school infantry subalterns of the first war but lower-middleclass boys chosen for their intelligence and education. Their numbers exceeded the British Army officers killed in the Great War. They went to their deaths with great courage, against high odds. They were as much the victims of the bombing campaign as the Germans they killed. Far from saving lives the strategic bombing offensive was, as Taylor has said, the Somme of 1939-45, and Harris its Haig.

If one wished to praise Harris it would be by comparing him with Churchill on whose reputation area bombing is the terrible stain. What was especially reprehensible was the way in which Churchill tried at the end of the war to dissociate himself from the bombing. As we have seen, he was an enthusiast for area bombing from the time he became Prime Minister, and he was egged on by his loathsome crony Lindemann (Lord Cherwell) who thought up the charmless expression 'de-housing', in the name of which 3.3 million dwellings were destroyed. After the war Churchill could still write — privately — to an air marshal: "We should never allow ourselves to apologise for what we did to , Germany'. But he had the instincts of a professional politician, and foresaw a reaction. On 28 March 1945 he drafted a memorandum: 'It seems to me the moment has come when the question of bombing of German cities simply for the sake of increasing the terror, though under other pretexts, should be reviewed. . . The destruction of Dresden remains a serious query against the conduct of Allied bombing.' The Air MinisrrY forced Churchill to withdraw this selfserving document, but he had his revenge. Churchill did not mention Bomber Command in his victory broadcast, no campaign medal was struck for its aircrew, Harris — who is still with us at 87, living in South Africa — Was not allowed to issue a final dispatch and received no peerage. Churchill attempted, With some degree of success, to pretend that the bombing campaign had never happened, and that if it had, it was nothing to do with him.

The central phrase of my opening sentence requires explanation, though not qualifica tion, lest Mr David Irving should quote it out Of context. The crimes of National Socialism, Which were inspired and approved by Hitler, Were without parallel in history but they were not war crimes. Nor were Stalin's, for that matter. Extermination and slave labour have no necessary connection with war. Both Germany and Russia committed what could correctly be called war crimes, but these were outdone by the British bombing campaign. There is a question of profound interest here which Mr Hastings does not explore. Liddell-Hart commented after the 1000Bomber raid on Cologne in May 1942 Harris's first great publicity stunt — that It was 'the most barbarous, and unskilled, way of winning a war that the world has yet seen'. It took an intelligent conservative, Liddell-Hart's confrere J.F.C. Fuller, to go further and 'see that totalitarian powers waged war as efficiently as they could. They had avoided strategic bombing because they recognised its inefficiency: neither Luftwaffe nor Red Air Force was ever seriously equipped for heavy bombing. He also noted the contradiction between a Policy of bombing aimed at the morale of the enemy population and the policy of Unconditional Surrender. For Fuller, 'the object of war is not slaughter and devastation but to persuade the enemy to change his mind'. Fuller wrote a fierce attack on the bombing campaign in August 1943 for the Evening Standard; its then editor Mr Michael Foot refused to publish it. It took a radical pacifist, the American Dwight Macdonald, to go further and suggest that there might be a deeper significance in the fact that it was the democracies that relied on strategic bombing, and built the atomic bomb. It was partly that the industrial democracies possessed the economic resources: even the junior partner, the United States, managed to spend some $43,000 million on bombing. But there was more to it than that. Dynastic autocrats, had fought limited wars with limited means. The second World war was a total war: it was a People's War; it was unlimited — Unconditional — in aim. The means were unlimited too. It was the age of collective responsibility and collective guilt. Bomber Command Was punishing the German people, as well as defeating them. Macdonald had commented early in 1944 that looking at Europe was 'like living in a house with a maniac who may rip up the pictures, burn the books, slash up the rugs and furniture at any moment'. He was appalled at the destruction of things as well as lives, and rightly so. The finest creations of the human spirit are not more or less precious than life itself. The question of whether it is better to destroy a great building or to destroy a child's life is best left to those who like idle, abstract speculation; neither should be destroyed.

It is the physical devastation that is still with us and which makes it impossible for an Englishman born after the war to travel through Germany without a sense of shame, seeing Hamburg and Berlin, seeing mediaeval Nuremburg which Allied aircraft burnt to the ground ana where Allied prosecutors later had the effrontery to accuse Goering and Kesselring of bombing Coventry and Rotterdam; seeing, worst of all, Wiirzburg (not mentioned by Mr Hastings), once the baroque gem of Europe. It was a town of such complete unimportance that it was left alone. Until that is, 16 March 1945, after Dresden, less than nine weeks before VE Day, when the German armies were on the point of final collapse and when there was nothing else left to destroy. That night, using considerable resources of human ingenuity and inventiveness, Bomber Command razed the town to the ground in slightly less than 20 minutes. Wiirzburg, like 600,000 Germans, had surrendered unconditionally.

Previous page

Previous page