ARTS

Opera

Spine-tingling

Rupert Christiansen

Ariane and Bluebeard (Grand Theatre, Leeds) Angas as the Doctor in the new ENO production of Berg's masterpiece reason — seemed to make life worth living, Wozzeck and even changed the way I thought about But hasn't it all got a bit out of hand lately? The Pavarotti business, the nauseating articles about how the Thatcher camp, pretension and an expensive even- ing out? How often is the original ideal of dramma per musica seriously realised? What's the point of it all? I don't want to get into arguments over this, please. I know that I am hardly the first to have asked such questions, and yes, I have read the book by Joseph Kerman. Tonight I'll probably be swooning over the last act of Andrea Chenier with the worst of them. But it does nag at me, all the same, especially at a time when the national appetite has become undiscriminatingly ravenous, and I feel I must at least warn Spectator readers that there are periods when I would rather listen to Capital Gold or stare at the damp patch on the ceiling, anything rather than submit myself yet again to the seductive darkness of the opera house.

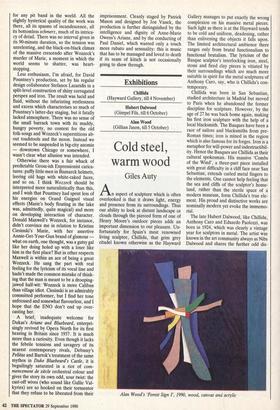

As if deliberately scheduled by the English National Opera to embarrass me, Berg's Wozzeck entirely dispels such lucubrations. It is a blazing masterpiece, Donald Maxwell as Wozzeck and Richard one of those rare operas — like Le nozze di Figaro, Pelleas and Falstaff— in which the music not only enriches the drama but adds another darker reason. Like Mr Prender- to it an entirely fresh dimension of signifi- gast in Decline and Fall, I have these cance. Stravinsky memorably praised its Tyranny of the Producer or the Decline of unique combination of 'totally spon- doubts. I don't mean that I deplore the taneous expressive freedom' with 'the most profound use of so-called abstract formal the Heldentenor (though I do); it's more devices': its tightness of construction is that I am just not completely convinced. complemented by a depth of moral vision Oh, I'm passionate enough about opera, which transforms the fragmentariness of ,God knows. It occupies an unhealthy Buchner's original text into a new coher- percentage of my waking thoughts. My ence. spine tingles and my eyes water at all the All this was realised at the London ;prescribed moments, and some unpre- Coliseum in the superlative account of the scribed ones too. I have experienced sever- score delivered by Mark Elder and the al evenings in the opera house which — sometimes for no very compelling aesthetic ENO's orchestra, currently, I bet, a match for any pit band in the world. All the slightly hysterical quality of the work was there, all its spasms of incandescence, all its bottomless schmerz, much of its intrica- cy of detail. There was no interval given in its 90-minute duration, so the tension was unrelenting, and the black-on-black climax of the massive crescendo after Wozzeck's murder of Marie, a moment in which the world seems to shatter, was heart- stopping.

Less enthusiasm, I'm afraid, for David Pountney's production, set by his regular design collaborator Stefanos Lazaridis in a split-level construction of shiny corrugated perspex and iron. The result was lucid and fluid, without the infuriating restlessness and excess which characterises so much of Pountney's latter-day staging, but it fatally lacked atmosphere. There was no sense of the small barrack town with its muddy, hungry poverty, no context for the old folk-songs and Wozzeck's superstitions ab- out toadstools and the moon. Instead we seemed to be suspended in big-city anomie — downtown Chicago or somewhere, I wasn't clear what allusion was intended. Otherwise there was a fair whack of predictable Grosz-ish Expressionist carica- tures: puffy little men in Bismarck helmets, leering old hags with white-caked faces, and so on. I think Wozzeck should be interpreted more naturalistically than this, and I wish that Pountney had spent less of his energies on Grand Guignol visual effects (Marie's body floating in the lake was, admittedly, quite magical) and more on developing interaction of character. Donald Maxwell's Wozzeck, for instance, didn't convince me in relation to Kristine Ciesinski's Marie, with her assertive Annie-Get-Your-Gun brand of glamour — what on earth, one thought, was a gutsy gal like her doing holed up with a loser like him in the first place? But in other respects Maxwell is within an ace of being a great Wozzeck. He sang the part with real feeling for the lyricism of its vocal line and hadn't made the common mistake of think- ing that the man is meant to be a drooping- jawed half-wit: Wozzeck is more Caliban than village idiot. Ciesinski is an admirably committed performer, but I find her tone unfocused and somewhat flavourless, and I hope that the ENO don't end up over- casting her.

A brief, inadequate welcome for Dukas's Ariane and Bluebeard, enterpri-

singly revived by Opera North for its first hearing in Britain since 1937. It is much more than a curiosity. Even though it lacks the febrile tensions and savagery of its

nearest contemporary rivals, Debussy's Pelleas and Bartok's treatment of the same mythos in Duke Bluebeard's Castle, it is beguilingly saturated in a riot of com- mencement de siècle orchestral colour and ' gives the story its own odd, sour twist: the cast-off wives (who sound like Gallic Val-

kyries) are so hooked on their tormentor that they refuse to be liberated from their imprisonment. Cleanly staged by Patrick Mason and designed by Joe Vanek, the production is further distinguished by the intelligence and dignity of Anne-Marie Owens's Ariane, and by the conducting of Paul Daniel, which wanted only a touch more rubato and sensuality: this is music that has to be massaged and loved to death if its seam of kitsch is not occasionally going to show through.

Previous page

Previous page