Instant Literature

Henry Wikoff, the American Chevalier. By Duncan Crow. (MacGibbon and Kee, 30s.) Its: recent years a good many people, myself not among them, have felt the want of a heavy, high- priced encyclopmdia of American literature. Weep no more, my ladies; the world's first com- bination doorstop and reference-work is now available from your friendly neighbourhood book-dealer.

Mr. Herzberg's prime difficulty is with that nasty word 'literature.' An encyclopaedist is by nature omnivorous, but he should never be in- discriminate. Definitions are useful from time to time, and to define means to exclude; if everything that has ever rolled off the presses of my unhappy country is to be called Literature, then the Typesetters' Union is in line for the Nobel Prize. 'Home, Sweet Home' is not Litera- ture, nor is Birth, by Zona Gale, and Personnel Administration—Its Principles and Practice has what might be called a doubtful ring. I am cer- tifiably astigmatic, and for this reason the con- nection between Dwight D. Eisenhower and Literature is now and has always been invisible to me. I am nevertheless fair-minded enough to pass on this helpful information:

Many books have been written about Eisen- hower's picturesque and extraordinary career.

(It may, of course, be true that Mr. Herzberg's sense of humour is more subtle than mine. In- cluded in the literary remains of Asa Don Dickinson, librarian, editor and critic, is The World's Best Books; Homer to Hemingway.)

Discrimination implies proportion, a quality necessarily absent from the present work. If Henry Wadsworth Longfellow is worth three columns, E. E. Cummings has earned more than one and a half.

It must be understood that the foundation of Mr. Herzberg's monument lies deep in the soil of American tradition. When I was a young prisoner of the New York educational system we were regularly ordered and encouraged to write book reports, in which we were to 'tell about' what we had read. The way to tell about a book is to write a three-page synopsis of it and add a paragraph specifying, that everyone will enjoy it. I should add in passing that the last sentence of Mr. Van Wyck Brooks's introduc- tion is a model for all young high-school students:

This book is invaluable to every American who cares for the shape of his country, its presence and expression in literary form; and it will be extremely useful as a primary work of reference in every household library for young and old.

The twenty-two lines entered under the head- ing The Great Gatsby constitute a book report at the university level. I don't want to frighten any- one, but if I read one more sentence like the following I shall take desperately violent action (burn down the Princeton library?): The 'Jazz Age,' Fitzgerald's constant subject, is exposed here in terms of its false glamor and cultural barrenness.

Now if you're going to run about being tiseful to anyone with an interest in the shape of American literature you had better find some- thing else to say, and something more. T. S. Eliot gave you a start when he called Gals by the most significant advance in American liction since Henry James.

Upon reflection, I find the idea of an encyclo- pedia of 'literature a curious one„ If I wanted information on, say, the basic laws of thermo- dynamics, I might consult the Britannica and save myself a good deal of time, effort and chit- chat with librarians, but 1 cannot see how could learn anything about American literature, or any other, without reading it. If I were in the position of not knowing where to begin (an un- likely case, considering the fact that American critics receive as much if not more attention in England than the native ones) I would either write to the United States Information Service or go to a library and grope along the shelves, hoping not to find anything like this:

In any event, the pleasure of reading Ameri- can poetry need not be diminished again by the fear that it somehow betrays an inferior national genius. This was undoubtedly the fear that distorted much of the cultural life of our forefathers.

In view of the horde of nonentities that Mr. Herzberg has immortalised I was surprised to notice the omission of Henry Wikoff (as well as Harry and Caresse Crosby, Benjamin Green, Arthur Higgins and Francis X. O'Keeffe). Wikoff and W. C. Fields are probably the only two in- teresting men ever to come out of Philadelphia, Pa., and they would have got on very well together.

Fields loved to play the mountebank who almost wins, the card shark who drops the extra ace on the table as he reaches for the pot, the con-man who buys back the gold-brick, the ladies' man who ends up in bed with a goat. The character is based on men like Wikoff, who was a type of scoundrel that nineteenth-century America seemed able to produce in limitless numbers. Wikoff's 'three decided fancies' were a newspaper, the theatre and women, but as far as I am concerned his greatest triumph was a short and inglorious career with the Foreign Office.

For reasons that only Cabinet Ministers could offer or understand, Lord Palmerston engaged Wikoff as a spy and propaganda agent. Wikoff was overjoyed, and his own description of his happy state is one of the high points of Mr. Crow's book :

To find one's self abruptly translated into the upper air of official life; . . . to know, in short, that you are actually enrolled on the staff of the British Foreign Office.. . . without being able to comprehend by what magic you ever got there; if all this was not enough to make your blood tingle and your head quite giddy on a fine bracing day in October, I would like to know what would.

It was a case of ignorance being served by incompetence. After Wikoff's inevitable dismissal he got his story into print at the most opportune moment and produced what the London news- papers called 'the scandal of the week.' Being a lone male in an age without television, tape- recorders or swimming-pools, he nudged the Government instead of rocking it and stumbled on his way, spreading alarm and despondency at every step.

Mr. Crow writes a roundabout Victorian prose, possibly to suit his subject, and he knows a funny story when he sees one. A carefully selected edition of Wikoff's memoirs might not be a bad idea.

PETER COHEN

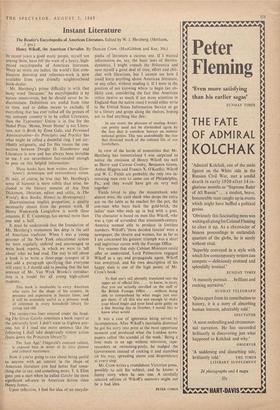

Previous page

Previous page