THE RUNNING MAN

Philip Delves Broughton has been watching

the next president of the United States (probably), and he likes what he sees

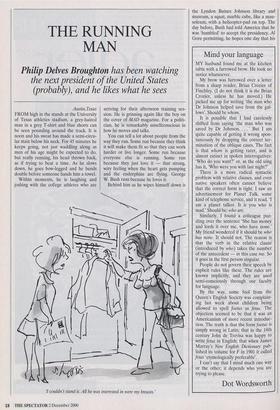

Austin, Texas FROM high in the stands at the University of Texas athletics stadium, a grey-haired man in a grey T-shirt and blue shorts can be seen pounding around the track. It is noon and his sweat has made a semi-circu- lar stain below his neck. For 45 minutes he keeps going, not just waddling along as men of his age might be expected to do, but really running, his head thrown back, as if trying to beat a time. As he slows down, he goes bow-legged and he bends double before someone hands him a towel.

Within moments, he is laughing and joshing with the college athletes who are arriving for their afternoon training ses- sion. He is grinning again like the boy on the cover of MAD magazine. For a politi- cian, he is remarkably unselfconscious in how he moves and talks.

You can tell a lot about people from the way they run. Some run because they think it will make them fit so that they can work harder or live longer. Some run because everyone else is running. Some run because they just love it — that strong, wiry feeling when the heart gets pumping and the endorphins are flying. George W. Bush runs because he loves it.

Behind him as he wipes himself down is the Lyndon Baines Johnson library and museum, a squat, marble cube, like a mau- soleum, with a helicopter-pad on top. The day before, Bush had told America that he was 'humbled' to accept the presidency. Al Gore permitting, he hopes one day that his own presidential library will feature on any tour of Austin.

For Bush, Austin is home in more than just a physical sense. You can see all that Bush is about in Texas's funky, affluent cap- ital, much as you could tell a lot about Bill Clinton from Little Rock, Arkansas. At noon, as the governor leaves his mansion for his run, scores of office workers and stu- dents from the University of Texas are also hitting the jogging tracks that snake through the city. In Washington the pundits laugh at Bush's light work-day, preferring Al Gore's 24-hour schedule; in Austin Bush seems perfectly normal.

Al Gore has nowhere like this, no place you can pin him to. Gore has activists and Democratic dependents behind him, but no real base. There is no such thing really as a Goreite. His home state, Tennessee, did not even vote for him in this election. People love Bush in Austin and he took Texas by nearly three to one.

On the Friday before election day, I went to see an American football game involving Austin High School, which Bush's twin daughters attended until last year, to try to see more of what formed Bush. The game was played under flood- lights at a stadium on the city's edge and, despite pouring rain, several hundred par- ents and friends sat in their anoraks cheer- ing on the Maroons. Many of them knew the Bushes.

'Governor Bush would come to games even though his daughters weren't involved,' said the mother of one of the team's defensive tacklers, as she huddled on a ramp into the stadium. 'Such a nice family.' Looking out at the cheerleaders, soaking but still cheering, the rows of devoted, well-to-do parents eating hot- dogs under their umbrellas, the light sprin- kling of black and Hispanic faces in the Crowd, it was easy to see the new Texas roots of the governor's political vision.

Why can't the rest of America be like this? he must wonder — a place where parents care enough about their children and schools to sit happily through the rain and then pile their soggy children into sports utility vehicles for the ride home. If only the world could mimic the miniature world of Austin High School, he must sigh, where everyone from aspiring president to computer billionaire to Mexican immi- grant mingles in the parking lot talking about a football game.

Democrats call Bush's utopia trivial. But at least it exists. He is not given to glib abstractions, and everything he says or does feels concrete. When he talks about his faith, he talks about it with a certainty that seems to forbid challenges. He is no rela- twist on religion. When he talks about com- passionate conservatism, he is describing the values of a way of life he knows well. Critics of Bush say that he lacks the mental ability to think abstractly. But it is not a gift much valued in the practical world of Texas politics. High-falutin think- ing is for the professors — and Al Gore.

Despite getting worse grades than Bush at university and dropping out of two grad- uate schools with dreadful exam results while Bush was earning his MBA at Har- vard, Gore has cultivated the impression that Bush is a moron and that he is up there with Isaiah Berlin and Stephen Hawking. Unfortunately, he lacks the clari- ty of a great teacher, or an honest man.

After he makes a speech, Gore's cam- paign team telephones reporters asking if they noted the vice-president's lofty think- ing: 'Did you get the bit where he talked about safeguarding American democracy?'

The downside to this loftiness is that for Gore everything is politics. Nothing is just itself. When he attended all of his son's school football games this year, he made a point of telling the New York Times, which used the fact to write a favourable piece about his family values. When he wishes to appear relaxed, he corrals his entire family into public games of touch football. Even going to the cine- ma becomes a political act when in the week after the election he went with Joe Lieberman to see a film called Men of Honour. When Bush, by contrast, slams down the shutters on his private life, they stay shut. He guards what he cares about from being swept into public life.

Al Gore's abstractions have now left him imprisoned in a Dr Strangelove world, con- vinced that the Republicans have done him in. He stalks his dining-room, scream- ing at his two laptop computers, bellowing for more polls that will tell him what he wants to hear. Occasionally, he emerges to jog swaddled in tracksuits and fleeces. His large thighs brush against each other as he rolls along. He would lose more weight running to a sweet shop.

What makes it worse is that, down in Texas, the opponent he holds in con- tempt is running hard and straight, smil- ing as he goes.

Previous page

Previous page