Male and female created He them?

Philip MacCann

PERFIDIOUS MAN by Will Self and David Gamble Viking, £12.99, pp. 154 It is roughly 40 years since women began exploring the social and historical roots of their own oppression and inviting men to do the same. There is now general agree- ment that, whilst maleness and femaleness are inborn, their associated characteristics — masculinity and femininity — are more (some say purely) culturally determined: masculinity need not embody power, nor femininity fragility or tenderness.

Yet gender characteristics remain shaped by sexual appeal and even liberated individuals continue to hope for traditional qualities. What John Berger said of men in 1972 remains largely true: a man's pres- ence 'is dependent upon the promise of power which he embodies. If the promise is large and credible his presence is striking. If it is small or incredible, he is found to have little presence.' One may even say that men remain laddish because women select laddish men to reproduce with. And their harsh critique of masculinity (involv- ing stripping men of their authority yet demanding it once again) has encouraged intense academic agony over its limitations, insecurities, death and possible transfor- mation (The End of Masculinity by John Madnnes is an ideological, thorough exploration).

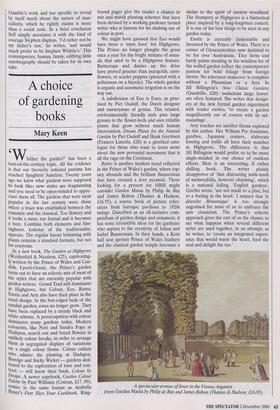

In this context of lively debate Perfidious Man purports to explore some absurd questions: 'What, at this stage in human history, and at this moment in the evolu- tion of the species, is the point of men?' Happily, no answer is attempted, as this is little more than a coffee-table book. David Gamble's beautiful, eloquent black-and- white prints capture a variety of modern estranged men in an inspiring range of public and intimate moments. The theme is that there is no theme and perhaps these portraits are too aesthetic and interesting in their own right to express the ordinari- ness of masculinity.

Will Self provides only a brief introduc- tion about his childhood relationship with his father, though a more colourful and harrowing autobiographical snippet could hardly be found. This professor of political science at the London School of Eco- nomics, endowed with a stubby and circum- cised penis, a virgin until his early thirties, lived in a 'compulsively sexualised world', making up for lost time. His wife hated him and taught the son to slow-handclap him. Devoid of any positive role model, the bruised adult now writes, 'When I became a man I hung on to childish things . . . almost any competitive situation made me feel . . . tiny-dicked.' What marks this writ- ing out as excellent, to my mind, is the compulsive loyalty to truth and style, what- ever the personal cost to the author. To explore masculinity further Self decides to interview 'someone who had been compelled to assert it while everyone around them was denying it'. So the major part of the text is not Self s at all, but the life story in his own words of Stephen Whittle, a female-to-male transsexual and lecturer in law at Manchester University. Tragically born with a female body, yet experiencing a male psychology, Stephen spent his life fighting to change sexual identity. As attitudes became more toler- ant, he was finally permitted this right and now lives with his female partner and chil- dren. (In Gamble's photograph he looks like Donald Pleasence.) His story is of peripheral relevance to Gamble's work and too specific to reveal by itself much about the nature of mas- culinity, which he rightly claims is more than a social code. In a brief conclusion Self simply associates it with the kind of courage Stephen displays. 'I'd rather not be my father's son,' he writes, 'and would much prefer to be Stephen Whittle's.' This contemporary, human, funny, edifying little autobiography should be taken for its own sake.

Previous page

Previous page