Interrogation conducted by civilised methods

Zenga Longmore

DIALOGUES by Naim Attallah Quartet, £17.99, pp. 327 The world of letters owes a great debt to Nairn Attallah, proprietor of Quartet Books, The Women's Press and two maga- zines — the Literary Review and the Oldie. His own writings consist mainly of percep- tive interviews with well-known personali- ties which regularly appear in the Oldie. This book contains his latest and last inter- views, though it is to be hoped that he can be persuaded to write more.

. His interview technique involves exten- sive research, and at times he appears to know more about his interviewees than they do. 'You grew up in considerable Poverty in Widnes.' What can bemused Lord Ashley do but agree? 'Your mother died, as you put it, "extremely distressing- ly" of Alzheimer's disease and you have said that you would prefer to be given a pill than to go through that.' The writer Claire Tomalin replies, 'I did say to Michael that If I started getting confused he was to give me a pill, and he replied I was quite con- fused already.' She then launches into autobiography. Perhaps this is Attallah's real talent — to be a springboard from Which his subjects can leap into flights of eloquence. In a sense, this is a collection of ,13nni-autobiographies. All the frills are cut. Oh goshee and `Blimey! I dunnos' are left to the reader's imagination. Any issue Attallah cares to discuss, however embarrassing, is thrust at the interviewee with painfully probing tenacity. What about sex?' he asks the reticent Ray- mond Briggs. Raymond explains that dur- ing his adolescent years people were fairly moral. 'And were you shy with women as a young man?' Naim presses. 'Oh yes, abso- lutely,' replies Raymond, and explains his struggle, as a five-foot two-inch, piping- voiced 14-year-old to attract gorgeous 16- year-old girls. 'But later on in life, did you consider sex important?' It is only Naim's sensitivity which keeps him on the thy side of slimy.

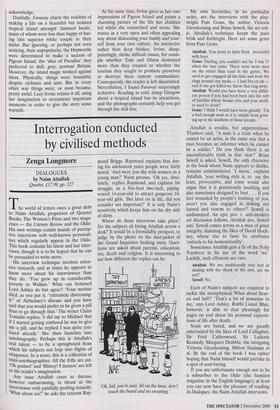

Where do these interviews take place? Do the subjects sit facing Attallah across a desk? It would be a formidable prospect, to judge by the photo on the dust-jacket of the Grand Inquisitor looking stern. Ques- tions are asked about parents, education, sex, death and religion. It is interesting to see how different the replies can be. My own favourites, in no particular order, are the interviews with the play- wright Pam Gems, the author Victoria Glendenning and Brian Sewell, the art crit- ic. Attallah's technique keeps the pace brisk and forthright. Here are some gems from Pam Gems.

Attallah: You seem to have been successful with boys.

Gems: Darling, you couldn't not be. I was 15 when the war came. There were more men on the street than sand in the gutter. We used to get engaged all the time and wear the rings around our necks — I had five or six — and if one got killed we threw that ring away. Attallah: Would you have been a very differ- ent person if you had been born into the sort of families whose houses you and your moth- er used to clean?

Gems: I think I would have been ghastly. I'm a bad enough snob as it is, simply from grow- ing up in the kitchens of those people.

Attallah is erudite, but unpretentious. 'Flaubert said, "A man is a critic when he cannot be an artist, in the same way that a man becomes an informer when he cannot be a soldier." Do you think there is an uncomfortable truth in that view?' Brian Sewell is asked. Sewell, the only character in the book whom Nairn appears to dislike, remains unintimidated. 'I mean,' explains Attallah, 'your writing style is, to say the least, provocative, and some would also argue that it is gratuitously insulting and also sometimes designed to hurt . . . If you feel wounded by people's loathing of you, aren't you also engaged in dishing out hatred and venom to others?' Sewell is undismayed. An epic pro- v. anti-modern art discussion follows, Attallah pro, Sewell anti. Sewell comes across as a man of great integrity, damning the likes of David Hock- ney, whose rise to fame he attributes 'entirely to his homosexuality'.

Sometimes Attallah gets a fit of the Polly Toynbees in his use of the word 'we'. Luckily, such effusions are rare.

Attallah: We are traditionally very bad at dealing with the shock of the new, are we not?

Sewell: No.

Each of Naim's subjects are required to tackle the metaphysical.'What about heav- en and hell?' That's a bit of nonsense to me,' says Lord Ashley. Rabbi Lionel Blue, however, is able to chat pleasingly for pages on end about his personal expecta- tions of life after death.

Souls are bared, and we are greatly entertained by the likes of Lord Callaghan, Sir Fred Catherwood, Sir Ludovic Kennedy, Margaret Drabble, the intriguing Victoria Glendenning, Milton Shulman et al. By the end of the book I was rather hoping that Naim himself would partake in a spot of soul-baring.

If you are unfortunate enough not to be a subscriber to the Oldie (the funniest magazine in the English language), at least you can now have the pleasure of reading, in Dialogues, the Naim Attallah interviews.

Previous page

Previous page