Where the wild things were

Patrick Skene Catling

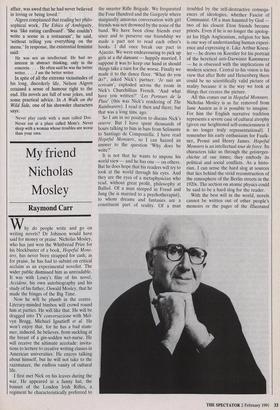

NELSON ALGREN: A LIFE ON THE WILD SIDE by Bettina Drew Bloomsbury, f20, pp. 416 Nelson Algren, the Chicago novelist (1909-1981), after years of neglect, is being rehabilitated. Forty years or so after the wild heyday of his antisocial realism, his indignation on behalf of the under- privileged still has a sharp bite.

He was once regarded as one of the most daringly outspoken chroniclers of Amer- ican low life. His most successful novels, The Man with the Golden Arm and A Walk on the Wild Side, were controversial best- sellers and have recently been republished here (Picador, £5.99 each). They are salu- tarily disturbing and worth reading. Algren was an idealist of the left who wrote of his ideals only implicitly, by stating their oppo- sites. His message is certainly clear, that America shows little mercy to misfits who fail to adapt to the capitalist system.

The pimps, whores, gamblers, drug addicts, thieves and hoboes of the Depress- ion now appear obviously to have been the prey rather than the predators of society quite harmless really, compared with the powerful organisations of modern interna- tional crime.

Richard Wright, the black author of Native Son, called Algren the 'Proust of the proletariat'. Malcolm Cowley, the liberal critic, praised him as 'a poet of the Chicago slums'. Leslie Fiedler, a lesser critic, called him 'the bard of the stumble- bum'. Hemingway, in a characteristic assessment of writing as an expression of pugnacious rivalry, said that Algren could `write the pants off [James T.] Farrell', the creator of Studs Lonigan. Mailer described Algren as the 'grand Odd-Ball' of Amer- ican letters. James Baldwin called him 'an honorable, well meaning white square'. Algren said he liked to think of himself as `the poor man's Dostoevsky'. I'm grateful to Bettina Drew for this collection of appraisals.

As a graduate student at City College of New York, Miss Drew was doing research for her master's thesis on the radical American literature of the 1930s when she was surprised by the paucity of published information about Algren. Rightly regard- ing him as one of the foremost radical novelists of that period, she decided to make good the deficiency. This magisterial biography is the admirable result. It is an instructive and entertaining work of thor- ough scholarship, evidently written with enthusiasm and care.

Born in Detroit, the son of an overwork- ed, underpaid machinist who kept drifting from job to job, Nelson Algren Abraham was named after his Swedish paternal grandfather, who had assumed his Jewish surname after his conversion to Judaism. Nelson's maternal grandparents were German-Jewish immigrants.

When he was four, his family moved to Chicago. He feared his illiterate mother, who habitually beat him; loved his father and adored an older sister. The account of his early years provides plenty of material for Freudian analysis. For ever after, his relations with women were ambivalent. He craved them but his capacity for love was limited; he always eventually estranged them.

He worked his way through the Uni- versity of Illinois, mowing lawns and wait- ing on tables. He read a lot: 'His voracious reading encouraged him to question the structure of organised society.' He knew few, if any, university women, but dating them would mean time away from books, money for fancy meals, and frivolous entertainment with no guarantee of sex.' At six o'clock every morning he took a cold bath but did not manage to suppress an early interest in prostitutes.

As an undergraduate, he turned his attention from sociology to journalism. In his senior year, he worked part-time as a police reporter for The Daily Mini. Cover- ing Chicago's courts and jails, he wrote about 'homeless transients, stewbums [alcoholic indigents], and petty thieves; crimes of adultery, drunkenness, vandal- ism, burglary, and murder' — and 'enjoyed the assignment'.

Having repudiated religion, 'he consi- dered himself neither Jew nor Gentile', and dropped Abraham from his by-line. By graduation, he was already an outsider. Unemployed, he became an expert on the hard life of a vagrant underdog, by becom- ing one.

He headed south, travelling in freight trains. In the French Quarter of New Orleans, he found a colourful assortment of the desperate men and women who inhabit his reportorial fiction. He had a good ear for the speech of low dives and the gutter.

A compulsive gambler with a suicidal lack of skill and luck, he wasted most of the money he made with short stories and novels. Even during his years of success, he was always close to bankruptcy.

In Alpine, Texas, a small college town, he stole a typewriter and was soon caught. This unhappy episode enabled him to observe prison life for several weeks and provided some authentic copy on a con- victs' kangaroo court.

Hardly surprisingly, Algren failed as a husband. As his biographer puts it, 'the failure of love [was] a theme that would mark not only many Algren stories but also Algren's life.' When he was drafted, he was such a conspicuously sloppy soldier that a sergeant nicknamed him 'The Shame of the Nation'.

`Being a loser', Algren wrote, 'I speak only for losers.'

In one celebrated love affair, he was a winner for quite a long time. For 17 years, he was the lover of Simone de Beauvoir. They met when she was nearly 40, and, Miss Drew records, 'Simone said later that she experienced her first true orgasm with Nelson.' Perhaps passion endured as long as it did because they lived apart most of the time. She spent many months each year in Paris, while Algren stayed in Chicago. There was never any possibility that he would tempt her to sever her connection with Sartre, who complaisantly tolerated her occasional absences.

When Algren and she separated for the last time, there was consequential mutual acrimony. 'Lewis Brogan, Algren's fiction- al counterpart in The Mandarins, de Beauvoir's novel that recounted their love affair, was awed that he had never believed in loving or being loved.'

Algren complained that reading her philo- sophical work, The Ethics of Ambiguity, was 'like eating cardboard'. 'She couldn't write a scene in a restaurant', he said, `without telling you everything on the menu.' In response, the existential feminist said:

He was not an intellectual. He had no interest in abstract thinking, only in the concrete. . . . He often said he was the better writer. . . . I am the better writer.

In spite of all the extreme vicissitudes of his long, disorderly life, Nelson Algren retained a sense of humour right to the end. His novels are full of sour jokes, and some practical advice. In A Walk on the Wild Side, one of his shrewder characters says:

Never play cards with a man called Doc. Never eat at a place called Mom's. Never sleep with a woman whose troubles are worse than your own.

Previous page

Previous page