CHESS

Warlike moves

Raymond Keene

Chess, it is widely believed, originated as an Oriental paradigm of battle around two thousand years ago. Various legends explain chess as a war game, starting in India, but it has also been theorised that the beginnings of chess can be found in the tactical battle plans of Alexander the Great from his Persian campaigns and beyond. Military formations, such as the Alexan- drine phalanx and the parataxis, and that of the later Byzantine Emperor Alexius Comnenus (a known chess player), were, it has been suggested, based on the number 64, the total of squares on the chess board. In spite of its warlike origins, of whatever nature, chess remained, until the mid- fifteenth century, a game of slow strategic manoeuvre.

Nobody has produced a satisfactory ex- planation for the Renaissance explosion, the sudden and dramatic increase in the powers of the pieces, followed by the amazingly rapid dissemination throughout Europe of the new and dynamic style of play. I believe, though, that this connects powerfully with. a sudden perception of distance. In the 1453 siege of Constantin- ople artillery was employed as- a decisive weapon. The introduction of the mighty Queen on the chess board mirrors the contemporary advance in military technol- ogy. In addition, perspective in art, the microscope, the telescope, the transatlan- tic voyages of Columbus and others point to an overwhelmingly urgent and sudden appreciation of distance and time in human affairs. All this found an immediate echo on the chess board. The transformation has nothing to do with Joan of Arc, Queen Elizabeth I or general boredom with the old style of game. The new style simply expressed the onset of the Renaissance dynamic which helped to create the mod- ern world.

Over the centuries since the leap in piece power the most highly prized games have been those which recapture in clearest fashion the momentum of the bAttlefield. Bobby Fischer, renowned as he was for his ruthless determination, was admired more for the sheer force of his destructive power on the chess board. This particularly mani- fested itself in his ability to counterattack with Black, traditionally the defensive colour, even at the highest level. In the evolution of his playing style Kasparov, as I pointed out last week, is emulating Fischer's determination to grind on in equal positions, but, as the following game from the current World Cup tournament in Belfort shows, he is also capable of striking down powerful opponents with Black, just as Fischer did.

Beliavsky-Kasparov: World Cup, Belfort; Grunfeld Defence.

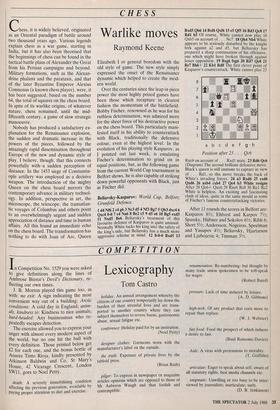

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 d5 4 Nf3 Bg7 5 Qb3 dxc4 6 Qxc4 0-0 7 e4 Na6 8 Be2 c5 9 d5 e6 10 Bg5 exd5 11 Nxd5 Be6 Beliavsky's treatment of this favourite defence of Kasparov is quite unusual. Normally White tucks his king into the safety of the king's side, but Beliavsky has a much more aggressive scheme in mind. 12 0-0-0 Bxd5 13 Rxd5 Qb6 14 Bxf6 Qxf6 15 e5 Q1'5 16 Bd3 Qc8 17 Rdl b5 Of course, White cannot now play 18 Qxb5 on account of. . . Nc7. 18 Qh4 Nb4 White appears to be seriously disturbed by the knight fork against a2 and d5, but Beliavsky has prepared a sharp continuation of his offensive, one which might have brok n through against lesser opposition. 19 Bxg6 f6 20 Rd7 Qe8 21 Re7 Bh6+ 22 Kbl Rd8 The first clever point of Kasparov's counterattack. White cannot play 23 Position after 23, . . Qc6 Rxe8 on account of. . Rxdl mate. 23 Rd6 Qc6 (Diagram) The second brilliant defensive move. Black's queen is still immune to capture in view of . . . Rdl, so this move breaks the back of White's invading forces. 24 a3 Rxd6 25 exd6 Qxd6 26 axb4 cxb4 27 Qe4 b3 White resigns After 28 Qe6+ Qxe6 29 Rxe6 Rc8 30 Rel Rc2 White is helpless. An exciting and fascinating clash of ideas, quite in the same mould as some of Fischer's famous counterattacking victories.

After 11 rounds the scores in Belfort are: Kasparov 81/2; Ehlvest and Karpov 71/2; Spassky, Hubner and Sokolov 61/2; Ribli 6; Short 51/2; Andersson, Nogeiras, Speelman and Yusupov 41/2; Beliavsky, Hjartarson and Ljubojevic 4; Timman 31/2.

Previous page

Previous page