PILGRIMAGE TO CALAIS

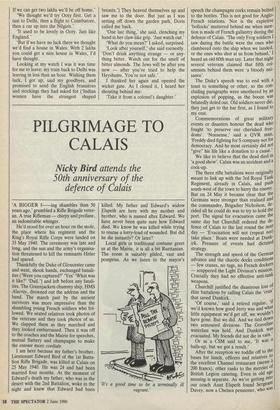

Nicky Bird attends the

50th anniversary of the defence of Calais

`A BIGGER f—ing shambles than 50 years ago,' grumbled a Rifle Brigade veter- an. A true Rifleman — chirpy and profane, an indomitable whinger.

He'd stood for over an hour on the mole, the place where his regiment and the King's Royal Rifle Corps were landed on 33 May 1940. The ceremony was late and long, and the sun and the army's organisa- tion threatened to kill the remnants Hitler had spared.

Thankfully the Duke of Gloucester came and went, shook hands, exchanged banali- ties (Were you captured?' Yes"What was it like?' Dull.') and left before any fatali- ties. The Greenjackets chummy ship, HMS Alacrity, drowned out the address and the band. The march past by the ancient survivors was more impressive than the shambling young French soldiers who fol- lowed. We seated relatives took photos of the veterans and they took photos of us. We clapped them as they marched and they looked embarrassed. Then it was off to the coaches and the Mairie for speeches, mutual flattery and champagne to make the entente more cordiale.

I am here because my father's brother, Lieutenant Edward Bird of the 1st Batta- lion Rifle Brigade, was killed at Calais on 25 May 1940. He was 24 and had been married four months. At the moment of Edward's death my father, who was in the desert with the 2nd Battalion, woke in the night and knew that Edward had been killed. My father and Edward's widow Elspeth are here with my mother and brother, who is named after Edward. We have never been quite sure how Edward died. We know he was killed while trying to rescue a lorry-load of wounded. But did he die instantly? Or later?

Local girls in traditional costume greet us at the Mairie, it is all a bit Ruritanian. The room is suitably gilded, vast and pompous. As we listen to the mayor's it's a good time to be a terminally ill vagrant.' speech the champagne corks remain bolted to the bottles. This is not good for Anglo- French relations. Nor is the expletive `bollocks' muttered behind me when men- tion is made of French gallantry during the defence of Calais. 'The only Frog soldiers I saw during the battle were the ones who clambered onto the ship when we landed, or the ones who shot at us from behind,' I heard an old 60th man say. Later that night several veterans claimed that fifth col- umnists behind them were 'a bloody nui- sance'.

The Duke's speech was to end with a toast to something or other, so the con- cluding paragraphs were smothered by an explosion of popping, as the booze was belatedly doled out. Old soldiers never die, they just get to the bar first, as I found to my cost. Commemorations of great military events or disasters honour the dead who fought `to preserve our cherished free- doms'. 'Nonsense,' said a QVR man, `Freddy died fighting for S company not for democracy. And he most certainly did not "give" his life like a donation to a cause.' We like to believe that the dead died in `a good show'. Calais was an accident and a cock-up. The three rifle battalions were originally meant to link up with the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment, already in Calais, and push south-west of the town to harry the enemy. But on 24 May it became clear that the Germans were stronger than realised and the commander, Brigadier Nicholson, de- cided all he could do was to try to hold the port. The signal for evacuation came the same day but Churchill ordered the de- fence of Calais to the last round the next day — 'Evacuation will not (repeat not) take place.' Boats were needed at Dunk- irk. Pressure of events had dictated strategy.

The strength and speed of the German advance and the chaotic docks conditions — few cranes, no tugs, no French dockers — scuppered the Light Division's mission. Crucially they had no effective anti-tank weapons. Churchill justified the disastrous loss of, elite battalions by calling Calais the `crux' that saved Dunkirk. `Of course,' said a retired regular, S we'd known how good Jerry was and what little equipment we'd get off, we wouldn't have gone. But we did. And we tied down two armoured divisions. The Graveline waterline was held. And Dunkirk was evacuated. My friends did not die in vain. Or as a CSM said to me, 'It was a balls-up, but we got a result.' After the reception we toddle off to the buses for lunch, officers and relatives to the excellent Channel restaurant (menu 200 francs), other ranks to the mercies or British Legion catering. Even in old age messing is separate. As we're getting into our coach Aunt Elspeth found Sergeant Davey, now a Chelsea pensioner, who was with Edward at the end. My father asks him how he did.

`The lorry full of RB wounded was hit some distance from our lines and the driver disabled. The wounded were trying to crawl out. Your brother ran from his trench to restart the lorry but was hit in the head. Here.' He points to his right temple. `He died immediately. When the fight was over I put his body in the back with the wounded myself. He was a good officer. He'd always tell you how to get off a charge. I've often wondered about his family. Goodbye, I won't see you again,' and he shook our hands and went to his coach, curiously comforted, as we were.

After lunch, in the hideous Place des Armes, Albert Speer's idea of a cosy square perhaps, the bands march up and down in the heat playing medleys from the Lloyd-Webber songbook. There are snip- ers on the roofs to protect the Duke, and a lone bugler on the pizza parlour.'What's he doing up there?' I ask a Greenjacket officer. 'Bugling'. The bandsmen charge around the square at the traditional furious pace. It goes on far too long but the French seem to like it. Then it's back to our coach for the trip to the Rifle Brigade cemetery and a tour of the battlefield.

In the coach a lady from Soldier maga- zine sits next to Elspeth. She talks of Edward. Elspeth doesn't want to. 'Can I Interview you?' says the lady. Pause. 'No,' says Elspeth and looks out of the window and is quiet. The tour leader hands out a list of Rifle Brigade officers and men buried in the cemetery. Edward's name is not among them. But he will be there under a name- less stone, 'Known unto God.'

It is a hot evening in the cemetery, a dignified plot hedged off from vast grotes- que local tombs. 'Bob's over there,' grunts one Rifleman to another and I glance in Bob's direction thinking I'll see a man with medals clanking. I see the grave of a man aged 19. Elspeth and Major Brush's widow stand in front of Jerry Duncanson's grave. He killed the last German of the battle and Was then killed himself. Earlier he'd shot down an enemy plane with his Bren. He'd enjoyed his last days hugely. Did you know him?' asks Mrs Brush. 'Yes,' says Elspeth, 'he lent us his house.' I find this all very nostalgic and moving,' says Mrs Brush and I hide behind the memorial in case she cries.

It has not been a tearful occasion, more a jolly reunion. But as we are leaving an old bugler stands rigid in front of the cross and blows the Last Post. His puff is not What it was and it is agony and yet we are all terribly affected by his wavering tribute. He finishes at last, thank God, and salutes. And at the end there is a telling moment. I ask a Rifleman who fought there to describe what happened fifty years ago. I haven't a clue,' he says. 'I hadn't then and I haven't now.'

Previous page

Previous page