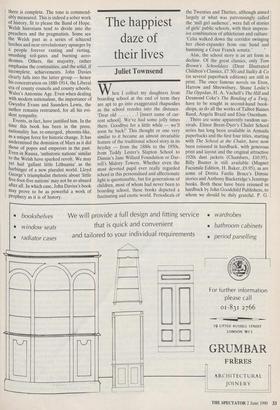

The happiest daze of their lives

Juliet Townsend

When I collect my daughters from boarding school at the end of term they are apt to go into exaggerated rhapsodies as the school recedes into the distance.

'Dear old ! [insert name of cur- rent school]. We've had some jolly times there. Goodbye for a little while — we'll soon be back!' This thought or one very similar to it became an almost invariable feature of the traditional school story in its heyday — from the 1880s to the 1950s, from Teddy Lester's Slapton School to Dimsie's Jane Willard Foundation or Dar- - rell's Malory • Towers. Whether even the most devoted pupil ever really regarded school in this personalised and affectionate light is questionable, but for generations of children, most of whom had never been to boarding school, these books depicted a fascinating and exotic world. Periodicals of the Twenties and Thirties, although aimed largely at what was patronisingly called the `mill girl audience', were full of stories of girls' public schools, with their impress- ive combination of athleticism and culture: `Celia walked down the corridor swinging her chest-expander from one hand and humming a Cesar Franck sonata.'

Alas, the school story is an art form in decline. Of the great classics, only Tom Brown's Schooldays (Dent Illustrated Children's Classics, £7.50) and Stalky & Co (in several paperback editions) are still in print. The once famous novels on Eton, Harrow and Shrewsbury, Shane Leslie's The Oppidan, H. A. Vachell's The Hill and Desmond Coke's The Bending of a Twig, have to be sought in second-hand book- shops, as do all the works of Talbot Baines Reed, Angela Brazil and Elsie Oxenham.

There are some apparently random sur- vivals. Elinor Brent-Dyer's Chalet School series has long been available in Armada paperbacks and the first four titles, starting with The School at the Chalet, have now been reissued in hardback, with generous print and layout and the original attractive 1920s dust jackets (Chambers, £10.95). Billy Bunter is still available (Magnet Facsimile Edition, H. Baker, f9.95), as are some of Dorita Fairlie Bruce's Dimsie stories and Anthony Buckeridge's Jennings books. Both these have been reissued in hardback by John Goodchild Publishers, to whom we should be duly grateful. P. G. Wodehouse's school stories are published in two Penguin Collections at £5.99: The Pothunters and Other School Stories, and The Gold Bat and Other School Stories; and Mike at Wrykyn is still available in hardback (Barrie & Jenkins, £9.95), but it appears that the second half of Mike, once published separately as Enter Psmith or Mike and Psmith, and one of the best of all school stories, is out of print.

A notable change in the subject-matter of children's books in the last 20 years has been the gradual introduction of stories about life in state schools, some, like the Grange Hill series, stimulated by television programmes. In several cases a whole series is set in the same school. One of the best of these is Gene Kemp's Cricklepit Combined School, famous for The Turbu- lent Term of Tyke Tiler. The most recent addition to this series is Just Ferret (Faber, £7.99), a laconic first-person account of the struggles of an outsider to fit in at a new school. Owen has led a roving life with his rootless father. He arrives at Cricklepit in the top year, at the age of 12, tough, bright, but unable to read. This is the first children's book I have come across which deals with the common problem of dyslex- ia, and it does so coolly, without sentiment and with hope. It is also a study in friendship, and spice is added by the extremely robust war against the school bullies. The fascination of school stories has always lain in the fact that the school itself, especially the circumscribed setting of the boarding school, presents a microcosm of the world outside. In it we find in concen- trated form the vices and virtues, ambition and scheming, crime and punishment, friendship and enmity of human society. Over the years, attitudes in school stories have changed to reflect those in the world at large. Some of the moral goal-posts have been subtly shifted. Cheating in the new grittier stories of life in the state sector, epitomised by the theft of the exam paper, that staple of a hundred stories, is no longer quite the black crime it once was. There is a grudging respect for the sharp operator who can fool the authorities, and the concepts of school honour and owning up are as dead as the Dodo. No longer could Jo in The School at the Chalet claim with total confidence, 'English girls always play the game!' This apparent decline is compensated for by an engaging humour and tolerance.

The multi-racial nature of many English schools today is also reflected in these books. Imran's Secret by Nadya Smith (Julia MacRae Books, £4.50), a story for younger children, sees Jubilee Park Prim- ary School through Moslem eyes. It addresses some common problems — the grandmother who speaks no English and the hazards of maypole dancing when, as Safina says, 'We never touch the boys, miss.' Religious questions have also taken on a new twist. An issue in lmran's Secret is swimming: 'It is against our religion for girls to take their clothes off in a public place.' In the old days it was East agonising to Tom Brown about why he never 'stop- ped the Sacrament'. Hindu customs, like the celebration of Davali, find a place in How's School Lizzie? by Anne Rooke (Blackie, £3.95). With its companion volume, Lizzie and Friends, it is a cosy introduction to school life for five-year- olds and deals sensibly and humorously with questions like race and disability without making an issue of them.

The author has the same breezy attitude to problems of health and hygiene. In Victorian school stories, illness and injury are common, often fatal and demanding extreme remedies. In Eric Or Little By Little, for instance, we read of the saintly and doomed Russell, 'He had sprained the knee and given the tibia an awkward twist . . . It was decided that the leg must be amputated.' The Lizzie books deal with the more trivial but equally widespread health hazards in present-day schools. "Mu—urn . . . Here's a letter for you. I've got nits . . ." The next afternoon Lizzie rushed out of school holding another letter. "What now?," said Mum. "Worms, I suppose".' There has always been a rich vein of humorous school stories, from Billy Bunter to Ginger Knut, the Boy who takes the Biscuit, in the old Champion comic. A good recent example is Jeremy Strong's Pandemonium at School (A & C Black, £4.95), the story of the anarchic supply teacher, Miss Pandemonium, who erupts into the rigid world of the DuBandon School and its hidebound headmaster, Mr Sharpnell. Lessons with Miss Pandemo- nium are certainly never boring. Too much yeast in her Friendship Cake makes it spread through the school like some deadly fungus. There is chaos when the children try to convert their bicycles into helicop- ters, and the headmaster and the school inspector both manage to end up fully clad in the swimming pool during the initiative test on how to cross the pool without get- ting wet.

Anne Digby is one of the very few people still writing about life in a girls' boarding school, and her Trebizon series is extremely popular. It is written in a rather slangy, casual way — the girls are always `meeting up' with each other and the text is full of exclamation marks — but the books are fast-moving and readable. It is re- freshing to find many of the traditional concerns of school stories — teenage friendships, success at games, the girl from the state school finding her feet in a different world — all surviving happily side by side with worries over GCSE course- work. The latest title is Ghost Term at Trebizon (Puffin, £1.99) and it is good to know that, here at least, the boarding- school story survives.

Previous page

Previous page